Fabrication of Nano-composites from the Radix of Angelica gigas Nakai by Hot Melt Extrusion Mediated Polymer Matrixs

© The Korean Society of Medicinal Crop Science. All rights reserved.

This is an Open-Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0 ) which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Abstract

The objective of this study was to make colloidal dispersions of the active compounds of radix of Angelica gigas Nakai that could be charaterized as nano-composites using hot melt extrusion (HME). Food grade hydrophilic polymer matrices were used to disperse these compound in aqueous media.

Extrudate solid formulations (ESFs) mediated by various HPMCs (hydroxypropyl methylcelluloses) and Na-Alg polymers made from ultrafine powder of the radix of Angelica gigas Nakai were developed through a physical crosslink method (HME) using an ionization agent (treatment with acetic acid) and different food grade polymers [HPMCs, such as HP55, CN40H, AN6 and sodium alignate (Na-Alg)]. X-ray powder diffraction (XRD) analysis confirmed the amorphization of crystal compounds in the HP55-mediated extrudate solid formulation (HP55-ESF). Differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) analysis indicated a lower enthalpy (ΔH = 10.62 J/g) of glass transition temperature (Tg) in the HP55-ESF than in the other formulations. Infrared fourier transform spectroscopy (FT-IR) revealed that new functional groups were produced in the HP55-ESF. The content of phenolic compounds, flavonoid (including decursin and decursinol angelate) content, and antioxidant activity increased by 5, 10, and 2 times in the HP55-ESF, respectively. The production of water soluble (61.5%) nano-sized (323 ㎚) particles was achieved in the HP55-ESF.

Nano-composites were developed herein utilizing melt-extruded solid dispersion technology, including food grade polymer enhanced nano dispersion (< 500 ㎚) of active compounds from the radix of Angelica gigas Nakai with enhanced solubility and bioavailability. These nano-composites of the radix of Angelica gigas Nakai can be developed and marketed as products with high therapeutic performance.

Keywords:

Angelica gigas Nakai, Food Grade Polymer, Hot Melt Extrusion, Nano-composite, Solid FormulationINTRODUCTION

Radix of Angelica gigas Nakai is an important herbal medicine in Korea and has several pharmacological properties to menopausal syndromes, anemia, abdominal pain, inhibition of breast cancer, and amenorrhea (Nam et al., 2018).

A. gigas Nakai has been studied extensively and found to contain a variety of substances including coumarins (Ryu et al., 1990). Coumarins are composed of decursin and decursinol angelate, which has long been used as a traditional medicine for the treatment of anemia, as a sedative, and as an anodyne or a tonic agent (Yook, 1990).

Most of the decursin and decursinol angelate metabolized to decursinol, more hydrophilic, it is low bioavailability and water solubility due to poorly and slowly absorbed across the gut and via the blood following oral and intravenous administrations (Kim et al., 2009).

Many herbal medicines such as Radix of A. gigas Nakai are used in functional food products; however, there is currently a great deal of concern over possible absorption, tissue distribution, metabolism, and elimination following oral administration associated with such pharmaceutical active compound in animal model and human body.

This point was explained that pharmaceutical active compound have strong intermolecular covalent bonds in the crystal lattice, the diverse range of structural components, the high bonding capacity within the molecules, and the large molecular weight of the endproduct make it less functional. (Khaledi, 1997; Khoddami et al., 2013).

Also, pharmaceutical industry is facing the challenge of having more and more pooly soluble drug molecules that have to developed into dosage forms so that high and reliable drug absorption can be guaranteed on being administered to patients (Breitkreutz, 1998).

Usually the drug company will seek a way to modify the molecule in a way that it become more soluble, different approach such as physical modification (salts, amorphous solid dispersions, and particle size reduction) and carrier or delivery systems (co-solvent, micelles, microemulsion, and nanopaticles) to overcome the solubility issues and enhancing the drug molecule's bioavailability of drug molecule (Perriea and Rades, 2010).

Janssens and Van den Mooter (2009) defined that solid dispersion is formulation of pooly souble compounds as solid dispersions might lead to particel size reduction, improve wetting, reduced agglomeration, changes in the physical state of the drug and possibly dispersion on an molecular level, according to the physical state of the solid dispersion.

Solid dispersion are system where one component is dispersed in a carrier (usualluy polymeric and often amorphous), it used ways to improve the solubility and hence the bioavailability of drug (Newman et al., 2012). Solid dispersion are prominent nowadays when preparation method such as hot-melt extrusion. In hot-melt extrusion (HME), extruder's screw the materials is mixed and dispersed at the same time, HME does by applying shear stress to the drug and the polymer, it generated energy by friction in order to overcome the crystal lattice energy to transform the drug into its amorphous form and to soften the polymer (Qi et al., 2011).

The application of food grade polymer in food and drug industry is getting special attention for the development of control delivery system. Hydroxypropyl ethylcellulose (HPMC) is a water soluble cellulose mainly used as a carrier material for the control release of active ingredients.

HPMC is hydrophilic and biocompatible polymer having capabilities of the hydration and gel forming which is prolong the releasing time of the active ingredients (Kadajji and Beageri, 2011). HPMC is extensively used in the food industry as a stabilizer, as an emulsifier, as a protective colloid, and as a thickener (BeMiller and Whistler, 1996).

HPMC is used as a raw material for coatings with moderate strength, moderate moisture and oxygen barrier properties, elasticity, transparency, and resistance to oil and fat (Kadajji and Beageri, 2011). It forms gel upon heating with gelation temperature of 75 - 90℃ during extrusion. By reducing the molar substitution of hydroxyl propyl group, the glass transition temperature of HPMC can be reduced to 40℃ (Deshmukh et al., 2017).

Recently, in order to produce sustaind release matrix tablets, hot melt extrudates of ethyl cellulose as a releasecontrolling polymer and HPMC as a hydrophillic drug relase modifier together with different drug such as iburofen and metoprolol tartrate were molded in to tablets using extruder (Vervaet et al., 2008; Quinten et al., 2008).

Another food grade carrier, alginate is a natural hydrophilic polysaccharide extracted from brown seaweed (Yang et al., 2011). This biopolymer is considered biocompatible, biodegradable, non-toxic and its use as food additive has been generally recognized as safe by Food and Drug Administration (Andersen et al., 2012).

As a food ingredient, the applications of alginate are based on three main properties: thickening, gelling, and film forming due to presence of reactive sites, such as hydroxyl and carbonyl groups along the backbone (Zia et al., 2015).

Application of alginate in food industry is being increasing due to its dynamic chemical and biological properties (Zia et al., 2015). In addition to alginate is increasingly used to encapsulate active compound, acting as a carrier for controlled delivery system and protective coating for fruits and vegetables (Qin et al., 2018).

Previously a group of researcher prepared nanocomposite of radix of A. gigas Nakai based on polymer and biopolymer to enhanced solubility and bioavailability (Piao et al., 2015), oral cancer therapy (Nam et al., 2017), control delivery system (Lee et al., 2016), brest cancer therapy (Lee et al., 2017a).

Researchers have discovered the compatible polymeric material for the preparation of hydrogel matrix in order to enhance solubility (Baird and Taylor, 2012; Shit and Shah, 2014). From the nutraceutical point of view, polymer control the rheological characteristics of food materials and prolong the releasing time.

In this regards, nano-composite of radix of A. gigas Nakai were prepared based on HPMC (HP55, CN40H and AN6) and Na-Alg to enhance solid dispersion of the active compound. This nano composite would be potentially enhance the nanonization, water solubility and amorphization of the active compound from A. gigas Nakai extrudate.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

1. Chemical and reagents

Acetic acid (1 M), citric acid, tween 80 (hydrophiliclipophilic balance, HLB : 15.0), span 80 (HLB : 4.3), phenolic reagent (Folin Ciocalteu, 2 N), sodium bicarbonate (Na2CO3), aluminum nitrate (AlNO3)3, potassium acetate (CH3CO2K), DPPH (2, 2-diphenyl-1 picryl hydrazyl), and acetic acid were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). Food grade sodium alginate was purchased from esfood, Pocheon, Korea and HPMCs (HP55, CN40H and AN6) were given as a donation by Lotte Fine Chemical. All other chemicals used were of analytical grade and purchased from Merck Chemical (Darmstadt, Germany). Deionized, distilled water (EC value < 0.3 μS·㎝−1) was used for sample preparation.

2. Preparation of ultrafine powder of radix of A. gigas Nakai

Coarse powder was prepared from freeze dried radix of Angelica gigas Nakai. Radix of A. gigas Nakai were milled into coarse powder by a pin crusher (JIC-P10-2; Myungsung Machine, Seoul, Korea) equipped with a 30- mesh sieve. The milled powder was fractionated using a sieve shaker (CG-213, Ro-Top, Chunggye Industrial Mfg. Co., Seoul, Korea) equipped with a series of sieves (F 20㎝).

The powder was passed through 300㎛ mesh size sieves, and unpassed particles were grinded again with the pin crusher. The coarse powders were pulverized and classified by a low temperature turbo mill (HKP-05; Korea Energy Technology Co., Ltd., Seoul, Korea). The temperature of the mill chamber was kept at −18℃, The ultrafine powder of radix of A. gigas Nakai was stored in a desiccator for the further use.

3. Solid formulation of ultrafine powder of radix of A. gigas Nakai with polymers using HME

Extrudate solid formulation of ultrafine powder of radix of A. gigas Nakai was developed using STS-25HS twinscrew HME (Hankook E.M. Ltd., Pyoung Taek, Korea) with polymers such as HPMCs (HP55, CN40H and AN6) and Na-Alg. HPMCs (10% w/w) and Na-Alg (5% w/w) were added with ultrafine powder of radix of A. gigas Nakai in extrusion processing.

First, acetic acid 0.1M was added to each formulation to facilitate the ionization. Before extrusion, ultrafine powder of radix of A. gigas Nakai and polymers were mixed well using electric blender.

The extruder was equipped with a round-shaped die (1㎜) at feeding rate 40 g/min, rpm 150 with high shear. Temperature profile from feeding zone to die was 80/100/ 100/80/70℃. The extrudate solid formulations (ESFs) mediated various HPMCs and Na-Alg polymers were drying in an oven at 50℃ then grinding for further analysis.

4. Particle size analysis

Extrudate solid formulations (ESFs) mediated various HPMCs and Na-Alg polymer (ESF-HP55, ESF-CN40H, ESF-AN6 and ESF-Na-Alg 0.5 g) was suspended in 50㎖ of distilled water. The supernatant was separated by centrifugation at 3,000 rpm for 10 min. The particle size of the supernatant was studied using a light-scattering spectrophotometer (ELS-Z1000; Otsuka Electronics, Tokyo, Japan) with three replications.

5. Solubility measurements

One gram of ESF-HP55, ESF-CN40H, ESF-AN6 and ESF-Na-Alg powders were suspended in 50㎖ of distilled water at room temperature, gently stirred for 1 h, and then centrifuged at 3,000 rpm for 10 mins. The supernatant was decanted into an evaporating dish of known weight. Water solubility was calculated by the formula described by Piao et al. (2015).

6. Infrared Fourier transform spectroscopy (FT-IR) analysis

Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FT-IR) spectra of ESF-HP55, ESF-CN40H, ESF-AN6 and ESF-Na-Alg were recorded on a Perkin-Elmer Model 1600 apparatus (Norwalk, CT, USA) using KBr stressed disks in the range of 4,000-400㎝−1.

Ten milligrams of each sample was positioned in contact with the attenuated total reflectance (ATR) plate. All spectra were subtracted against a background of air spectra. After every scan, a new reference of air background spectra was taken. The ATR plate was carefully cleaned by scrubbing with 70% isopropyl alcohol twice followed by drying with soft tissue before being filled in with the next sample, making it possible to dry the ATR plate.

7. Differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) analysis

The DSC curves of ESF-HP55, ESF-CN40H, ESF-AN6 and ESF-Na-Alg were obtained on a calorimeter (DSC Q2000, TA Instruments, New Castle, DE, USA) using aluminum crucibles with approximately 2.0 ± 0.1㎎ of samples under a nitrogen atmosphere, at a flow of 50㎖·min−1.

Rising temperature experiments were conducted at the temperature range of 20℃ to 250℃ with a heating rate of 10℃·min-1. Indium (melting point, 156.6℃) was used as the standard for equipment calibration. Data were analyzed using the software (Universal Analysis 2000, TA Instruments, New Castle, DE, USA).

8. X-ray powder diffraction (XRPD) analysis

The XRPD analysis of ESF-HP55, ESF-CN40H, ESFAN6 and ESF-Na-Alg were carried out in an X'Pert PRO XRD diffractometer (PANalytical B.V., Almelo, Netherlands) that scanned from 10 to 55 (2 min−1) on the 2 h scale and with CuK α1 radiation. The equipment was operated at 40.0㎸ and 30.0㎃. The data were analyzed using the Origin® version 8.1 software (Origin Lab, Northampton, MA, USA).

9. Extractions

One gram of ESF-HP55, ESF-CN40H, ESF-AN6 and ESF-Na-Alg were added to 100㎖ of distilled deionized water. The sample was shaken at 150 rpm, 25℃, using a shaking incubator (SI-900RF, JEIO TECH, Seoul, Korea) for 1 h. The sample was filtered through a 125㎜ filter paper (Advantech 5B, Toyo Roshi Kaisha, Tokyo, Japan), and then the extract was collected and stored in the refrigerator at −20℃ for further analysis

10. Determination of total phenolic contents (TPC)

The total phenolic contents of extracts in ESF-HP55, ESF-CN40H, ESF-AN6 and ESF-Na-Alg were determined by the Folin-Ciocalteu assay (Singleton and Rossi, 1965). The absorbance was measured at 725㎚ using a spectrophotometer (UV-1800 240V, Shimadzu Co., Kyoto, Japan). The TP was expressed as gallic acid equivalents (GAE) on a dry weight basis (㎎/100 g).

11. Determination of total flavonoid conten (TF)

The total flavonoid content (TF) of extracts in ESFHP55, ESF-CN40H, ESF-AN6 and ESF-Na-Alg were determined according to Ghimeray et al. (2014). The total flavonoids were measured using a spectrophotometer (UV- 1800 240V, Shimadzu Co., Kyoto, Japan) at 415㎚. The TF was expressed as ㎎/100 g coumarin equivalents on a dry weight basis.

12. DPPH free radical scavenging activity

The DPPH free radical scavenging activity in of extracts ESF-HP55, ESF-CN40H, ESF-AN6 and ESF-Na-Alg were determined on the basis of the scavenging activity of the stable 2, 2-diphenyl-1 picryl hydrazyl (DPPH) free radical according to methods described by Braca et al. (2003).

The absorbance was measured at 517㎚ using a spectrophotometer (UV-1800, Shimadzu Co., Kyoto, Japan). The percent inhibition activities of the sample were calculated against a blank sample using the following equation: inhibition (%) = (blank sample-extract sample/blank sample) × 100.

13. HPLC analysis of decursin and decursinol angelate

Contents of decursin and decursinol angelate was determined in ESF-HP55, ESF-CN40H, ESF-AN6 and ESF-Na-Alg by HPLC. An HPLC system (CBM-20A, Shimadzu Co., Ltd., Japan) with two gradient pump systems (LC-20AT, Shimadzu Co., Ltd., Japan), a C18 column (Kinetex, 100 × 4.6㎜, 2.6 micron, Phenomenex), an auto-sample injector (SIL-20A, Shimadzu Co., Ltd., Japan), a UV-detector (SPD-10A, Shimadzu Co., Ltd., Japan) and a column oven (35℃, CTO-20A, Shimadzu Co., Ltd., Japan) was used for analysis. Solvent A was 0.4% formic acid in water, and solvent B was acetonitrile. A gradient elution was used (0 - 15 min, 33 - 45% B; 15 - 30 min, 45 - 55% B; 30 - 40 min, 55 - 80% B; 40 - 45 min, 80 - 33% B). The flow rate was 1.0㎖/min, injection volume was 10㎕ and detection wavelength was 329㎚. Decursin and decursinol angelate at concentrations of 10, 20, 40, 60 and 80㎍/㎖ were prepared as standards.

14. Statistical analysis

All data were expressed as means ± SD of triplicate measurements. The obtained results were compared among the different polymer types using a paired t-test in order to observe the significant differences at the level of 5%. The paired t-test between mean values was analyzed by MINITAB version 16.0 (Minitab Inc., State College, PA, USA).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

1. Physical-chemical characteristics of extrudate solid formulations (ESFs) mediated various HPMCs and Na- Alg polymer

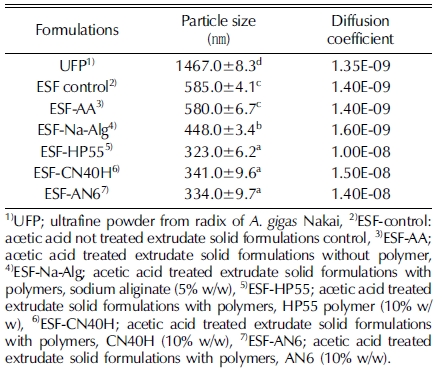

In our study, the particle size of the ultrafine powder of radix of A. gigas Nakai was recorded at 1,467㎚, whereas the particle size was reduced to 585㎚ at the ESFs without polymer adding. Among the ESFs mediated polymers such as HPMCs (HP55, CN40H and AN6) and Na-Alg, the least particle size (323㎚) was achieved in the HP55-ESF (Table 1).

Particle size and diffusion coefficient of extrudate solid formulations (ESFs) mediated various HPMCs and Na-Alg polymer.

Previously it is reported that HME extrusion is the most suitable process to form nano particle size (Maniruzzaman et al., 2012; Lee et al., 2017b). The particle size reduction strategy results in increased surface area, decreased diffusional distance, and increased dissolution rates (Repka et al., 2007; Merisko-Liversidge and Liversidge, 2008).

In the case of a limited dissolution rate, decreasing the particle size of the crystal form of active compounds can improve solubility. By downsizing the particle size, the surface will increase, this usually improves the wettability and hence dissoltion kinetics. Down sizing particles lead to molecular dispersed system.

HP55-ESF has the lowest particle size among ESFs mediated other HPMCs polymers and Na-Alg polymer, physical and chemical propertises of the HP55 might have direct influence to reduce the particle size.

Melt viscosity is important factor for determined extrudability of a polymer, polymer with a high molecular weight exhibit high melt viscosity and are difficult to extrude (Chokshi et al., 2005). Higher viscosity which means a higher shear stress with higher extrusion temperature might even lead to higher impurity level of ingredient in extrudated materials (Ghebremeskel et al., 2007) may cause degradation of active compounds and polymer. The high viscosity are not suitable.

For instant, HP55 possess 27 - 35% of phthalyl with viscosity of 32 - 48 cSt, pH < 5.5 where as CN40H and AN6 possess 19 - 24 % and 28 - 30% of methoxyl with viscosity of 4000 and 6 cSt, pH 5 - 8, respectively. On the other hand, Na-Alginate viscosity is 300 cSt and pH > 7.

Previous research have investigated the mechanism of hydrophilic HMPC effect on the particle size of the active compound (Miranda et al., 2007).

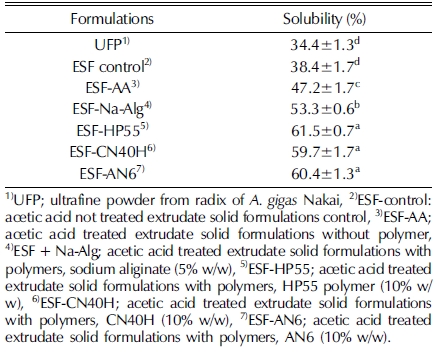

The results in Table 2 show that water solubility was improved in HP55-ESF (61.5%) compared to ultrafine powder of radix of A. gigas Nakai (34.4%), acetic acid not treated ESF control (38.4), acetic acid treated ESF control without polymer (47.2%).

Water solubility analysis of extrudate solid formulations (ESFs) mediated various HPMCs and Na-Alg polymer.

According to the Noyes-Whitney equation, particle size has a direct effect on the dissolution rate. The reduction of particle size increases the diffusional coefficient and nanonization.

In addition, an acidic solution (H+) increases the concentration gradient as well as enhances the dissolution rate through ionization process (Szekeres and Tombácz, 2012).

Amorphous nanoparticles exhibit very high saturation solubility compared to the crystalline form (Murdande et al., 2010). The HME process tends to make more channels to enhance the permeability and penetration of water into the core of the material’s matrix (Piao et al., 2015). Preparation of amorphous solid dispersion is a promising way to improve solubility. Cystalline compound exhibit poor water solubility, since the lattice energy must be overcome in order for dissolution (Li et al., 2013; Chuah et al., 2014).

The solubility of amorphous substances is higher solubility than the thermodynamically stable crystalline forms, because their internal bonding forces are weak. Solutions obtained from amorphous forms are supersaturated, and crystallization occurs once a crystal of the stable form develops (Gangurde et al., 2015).

In order to improve solubility, HPMC polymer carriers have been used because they readily generate amorphous forms and may be able to retain the amorphous nature of the compound (Leuner and Dressman, 2000). The higher solubility achieved in the HP55-ESF among ESFs mediated other HPMCs polymers and Na-Alg polymer. The reason might be due to the physicochemical characterization of the HP55 polymer.

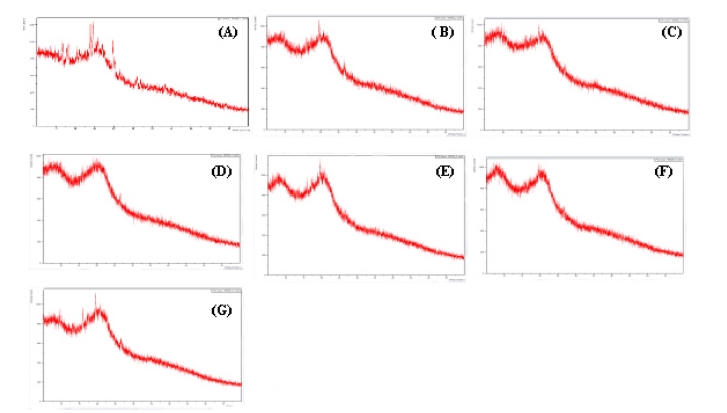

Fig. 1 shows the XRD diffractogram of the ESFs mediated other HPMCs polymers and Na-Alg polymer. The presence of a large number of peaks of different intensities in the diffractogram suggests the presence of unidentified complex substances in the ESFs mediated other HPMCs polymers and Na-Alg polymer. The HP55- ESF/CN40-ESF showed sharp diffraction peaks at angles between 25° and 30° with a lower degree of diffraction among the formulations. Application of pressure and agitation through an extrusion channel to mix materials together, subsequently forcing them out through a die to form an amorphous solid (Wilson et al., 2012).

XRD diffractogram of extrudate solid formulations (ESFs) mediated various HPMCs and Na-Alg polymer.(A); UFP; ultrafine powder from radix of A. gigas Nakai, (B); ESF-control: acetic acid not treated extrudate solid formulations control, (C); ESF-AA; acetic acid treated extrudate solid formulations without polymer, (D); ESF-Na-Alg; acetic acid treated extrudate solid formulations with polymers, sodium aliginate (5% w/w), (E); ESF-HP55; acetic acid treated extrudate solid formulations with polymers, HP55 polymer (10% w/w), (F); ESF-CN40H; acetic acid treated extrudate solid formulations with polymers, CN40H (10% w/w), (G); ESF-AN6; acetic acid treated extrudate solid formulations with polymers, AN6 (10% w/w).

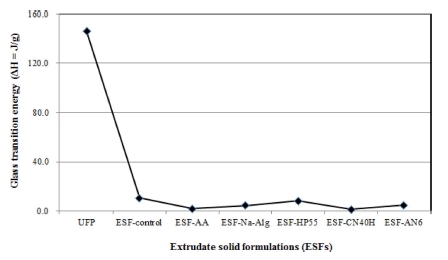

In the DSC analysis, it is determined the glass transition temperature (Tg) (Fig. 2). The extrudate solid formulations (ESFs) mediated various HPMCs and Na-Alg polymer had a lower ΔH value of Tg (> 10 J/g) than ultrafine powder of radix of A. gigas Nakai (ΔH of 146 J/g). It is well known that amorphous materials have a lower Tg compared to crystalline materials (Yoshioka et al., 1994).

Glass transition energy of extrudate solid formulations (ESFs) mediated various HPMCs and Na-Alg polymer.UFP; ultrafine powder from radix of A. gigas Nakai, ESFcontrol: acetic acid not treated extrudate solid formulations control, ESF-AA; acetic acid treated extrudate solid formulations without polymer, ESF-Na-Alg; acetic acid treated extrudate solid formulations with polymers, sodium aliginate (5% w/w), ESF-HP55; acetic acid treated extrudate solid formulations with polymers, HP55 polymer (10% w/w), ESF-CN40H; acetic acid treated extrudate solid formulations with polymers, CN40H (10% w/w), ESF-AN6; acetic acid treated extrudate solid formulations with polymers, AN6 (10% w/w). Mean values ± SD from triplicate separated experiments are shown. *Value marked by different letters in each column are significantly different by t-test (p<0.05) compared ultrafine powder from radix of A. gigas Nakai (UFP).

The ΔH of Tg of the extrudate solid formulations (ESFs) mediated various HPMCs and Na-Alg polymer appeared as very weak transitions, as more crystalline materials act as physical crosslinks that restrain the mobility of the amorphous regions (Zeleznak and Hoseney, 1987). The lowest ΔH was achieved in CN40-ESF where ΔH was recorded at 1.3 J/g.

DSC analyzes the system has been widely used to study the termal properties of materials used for example in hot melt extrusion. DSC can be used for the determination of Tg coupled with endothermic and exothermic phase transformation. The decreased Tg in the DSC scan of the HME indeicated that the drug is present in an amorphous or molecularly dissolved state rather than crystalline form (Singhal et al., 2011)

It is previously reported that the Tg of the formulation can be reduced to 40℃ by reducing the molar substitution of hydroxyl propyl group of HPMC (Deshmukh et al., 2017).

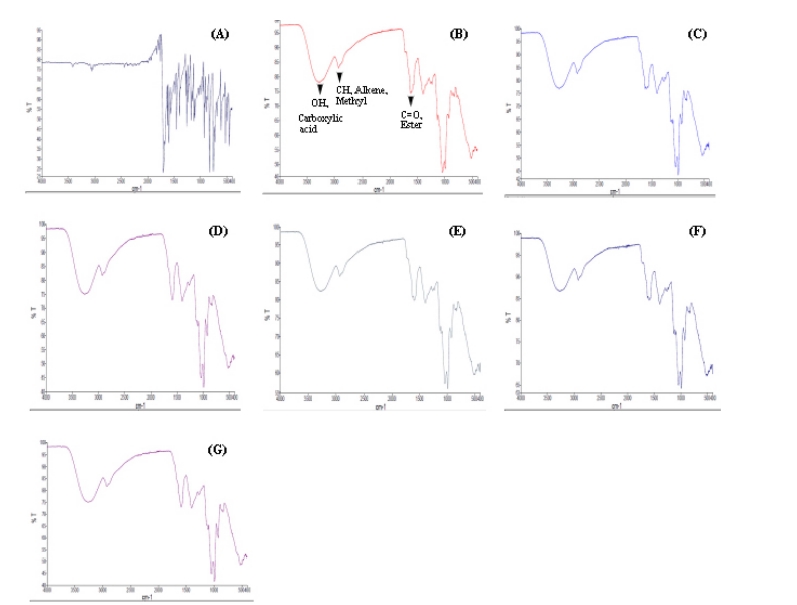

FT-IR spectroscopy investigated the new compounds produced in the ESFs, since it can detect a range of functional groups according to molecular structure (Cocchi et al., 2004; Tita et al., 2011). The spectra are presented in Fig. 3, which shows that the splitting peak in 1,700 - 3,500㎝−1 in ESFs, however, no splitting peak were observed in ultrafine powder from radix of A. gigas Nakai at the same range. Moreover, it is also observed that polymer matrix has no effect to produce new compound but HME.

FTIR chromatogram of extrudate solid formulations (ESFs) mediated various HPMCs and Na- Alg polymer.(A); UFP; ultrafine powder from radix of A. gigas Nakai, (B); ESF-control: acetic acid not treated extrudate solid formulations control, (C); ESF-AA; acetic acid treated extrudate solid formulations without polymer, (D); ESF-Na-Alg; acetic acid treated extrudate solid formulations with polymers, sodium aliginate (5% w/w), (E); ESF-HP55; acetic acid treated extrudate solid formulations with polymers, HP55 polymer (10% w/w), (F); ESF-CN40H; acetic acid treated extrudate solid formulations with polymers, CN40H (10% w/w), (G); ESF-AN6; acetic acid treated extrudate solid formulations with polymers, AN6 (10% w/w).

In the ESFs, there is a strong peak in wavelength of 2,800 - 3,000㎝−1, which correspond to alkane C-H stretching. Alkynes, benzene and its derivatives stretching occurred near 3,300㎝−1 in all ESFs except ultrafine powder of radix of A. gigas Nakai. The other prominent peaks at 1,700 - 1,500㎝−1 for all ESFs possess the characteristics of methylene and methyl bending. The peak region between 3,500 - 3,000㎝−1 is related to C-H, OH compounds (SP2), which we attribute to the nature of the organic compounds in the ESFs. Peak regions at < 2,000㎝−1 represent the carbonyl group compounds and the =C bonds in the aromatic rings and aromatic CH bonds on substituted rings (Silverstein et al., 2006). The peaks in the region < 1,500㎝−1 are related to carbon– oxygen bonds (CO) in ethers, esters, and carboxylic acids and are indicative of a wide variety of metabolites, such as tannins, flavonoids, and anthraquinones (Correia et al., 2011).

2. Analytical investigation of extrudate solid formulations (ESFs) mediated various HPMCs and Na-Alg polymer

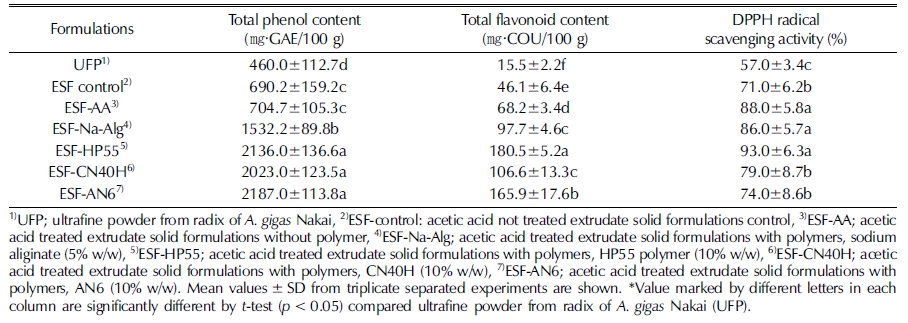

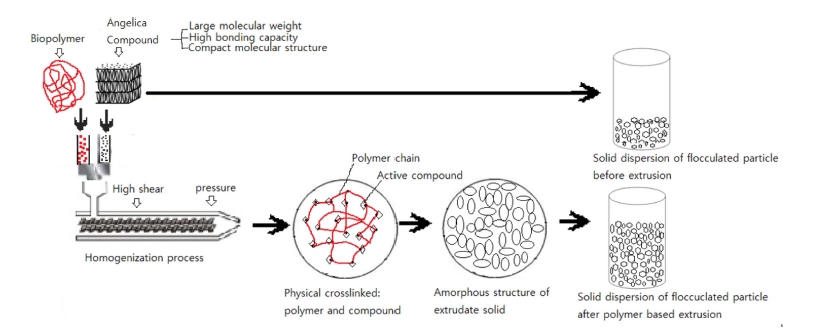

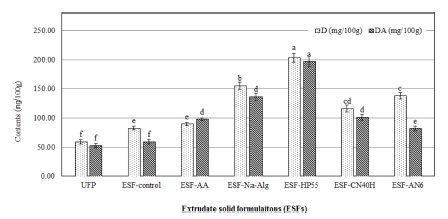

Among extrudate solid formulations (ESFs) mediated various HPMCs and Na-Alg polymer, ESF-HP55 showed the highest phenolic compound content (TPC; 2,136㎎· GAE/100g, TF: 180㎎·COU/100g, decursin; 200㎎/100g, decursinol angelate: 182㎎/100g, DPPH scavenging activity; 93%) (Table 3). The high level of compression and shear forces exerted on the crystalline structure of phenolic molecules lead to their disruption and defibration and the formation of an amorphous structure (Jurišić et al., 2015) (Fig. 4).d

Total phenolic content, total flavonoid and antioxidant activity of extract in extrudate solid formulations (ESFs) mediated various HPMCs and Na-Alg polymer.

Schematic illustration of extrudate solid formulations (ESFs) mediated various HPMCs and Na-Alg polymer and solid dispersions by hot melt extrusion process.

The physical crosslinking process by HME destructured the fiber matrix and caused phenolic compounds to be released into solution (Yu et al., 2002). HME increases the reactive surface areas of compounds and destructure the fiber matrix, thus causing enhanced decursin and decursinol angelate to be released into solution (Fig. 5). Therefore, the most likely explanation for the enhanced active compound extraction from the extrudate sample is the disruption of cell wall structure (Piao et al., 2015).

Contents of decursin and decursinol angelate of extrudate solid formulations (ESFs) mediated various HPMCs and Na-Alg polymer.UFP; ultrafine powder from radix of A. gigas Nakai, ESF-control: acetic acid not treated extrudate solid formulations control, ESF-AA; acetic acid treated extrudate solid formulations without polymer, ESF-Na-Alg; acetic acid treated extrudate solid formulations with polymers, sodium aliginate (5% w/w), ESF-HP55; acetic acid treated extrudate solid formulations with polymers, HP55 polymer (10% w/w), ESF-CN40H; acetic acid treated extrudate solid formulations with polymers, CN40H (10% w/w), ESFAN6; acetic acid treated extrudate solid formulations with polymers, AN6 (10% w/w). Mean values ± SD from triplicate separated experiments are shown. *Value marked by different letters in each column are significantly different by t-test (p < 0.05) compared ultrafine powder from radix of A. gigas Nakai (UFP).

In this study HP55 polymer enhanced the extraction efficiency of phenolic compound. It is explanied that due to hydrophilic characteristics and sol-gel behaviour of the HMPC polymer, extraction was facilitated (Kjoniksen et al., 2005). It is reported that HME enhances the dissolution rate of poorly water-soluble compounds (Hulsmann et al., 2000). Moreover, Hagi and Hatami (2010) determined higher levels of flavonoid were produced by the use of an acid-mediated solution from vegetables and medicinal plants.

3. Nano-composite by solid formulations (ESFs) mediated various HPMCs and Na-Alg polymer

It is concluded that ultrafine powder of radix of A. gigas Nakai has the micro size particle (1.4㎛) where as ESF without polymer converted to nano particle (585㎚). The least nano particle (323㎚) was attained in HP55- ESF nano-composite.

The solubility also increased to 61.5% in HP55-ESF nano-composite, whereas it appeared 34.4% in the ultrafine powder of radix of A. gigas Nakai. Development of the functional group, lower Tg temperature with amorphous compound was achieved in polymer mediated ESFs rather than ultrafine powder of radix of A. gigas Nakai.

In the same way, extraction of the total phenolic content and antioxidant activity was also increased in the extrudate solid formulations (ESFs) mediated various HPMCs and Na-Alg polymer compared to ultrafine powder of radix of A. gigas Nakai.

Poduction of drug-loaded nanoparticles for the poorly water-soluble drugs is an alternative and promising approach to overcome their low aqueous solubilities and the consequential low bioavailabilities (Muller et al., 2001).

Most pharmaceutical systems currently produced using HME for bioavailability-enhancement applications are performed to create an amorphous solid dispersion. Solid dispersions have received a significant amount of interest in the scientific literature as a method to improve the oral bioavailability of poorly water-soluble compounds (Breitenbach, 2002; Crowley et al., 2007). These systems contain at least one drug substance dispersed within an inert carrier such as polymer in the solid state (Sekiguchi and Obi, 1961; Chiou and Riegelman, 1971). A number of polymeric materials are utilized for melt-extruded solid dispersions processes have been used with great success for the production of nano-composite.

Both particle dissolution kinetics and solubility are size dependent. Thus, the dissolution of drug nanoparticles in vivo is usually accompanied by an increase in bioavailability (Hintz and Johnson, 1989; Borm et al., 2006).

In most cases, these materials and methods were designed for pharmaceutical technologies and have been applied to melt extrusion, which are commonly used for coatings, and binders, which are commonly used for granulations and compression. While these materials and methods have shown sufficient applicability in food and functional food industries, melt-extruded solid dispersions specifically designed for new functional food materials are in development of nano-composites and have recently begun to reach the market as well.

By being specifically designed melt-extruded solid dispersions for fabrication of nano-composites, these new functional food materials will provide benefits for processing and bioavailability enhancement.

Food processing of radix of Angelica gigas Nakai contain a majority of compounds with limited solubility that require formulation intervention to improve delivery. In this study, nano-composites have been developed utilizing melt-extruded solid dispersions technology to improve bioavailability. This nano-composites of radix of Angelica gigas Nakai developmental and marketed products to enable therapeutic performance.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by the Kangwon National University (2017520170416).

References

-

Andersen, T, Strand, BL, Formo, K, Alsberg, E, Christensen, BE, (2012), Alginates as biomaterials in tissue engineering, Carbohydrate Chemistry, 37, p227-258.

[https://doi.org/10.1039/9781849732765-00227]

-

Baird, JA, Taylor, LS, (2012), Evaluation of amorphous solid dispersion properties using thermal analysis techniques, Advance Drug Delivery Reviews, 64, p396-421, 21843564.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addr.2011.07.009]

- BeMiller JN and Whistler RL, (1996), Carbohydrates, Fennema, OR, (ed.), Food Chemistry, Marcel Dekker Inc., New York. NY, USA, p205-207.

-

Borm, P, Klaessig, FC, Landry, TD, Moudgil, B, Pauluhn, J, Thomas, K, Trottier, R, Wood, S, (2006), Research strategies for safety evaluation of nanomaterials. Part 5. Role of dissolution in biological fate and effects of nanoscale particles, Toxicological Sciences, 90, p23-32, 16396841.

[https://doi.org/10.1093/toxsci/kfj084]

-

Braca, A, Fico, G, Morelli, I, de Simone, F, Tome, F, de Tommasi, N, (2003), Antioxidant and free radical scavenging activity of flavonol glycosides from different Aconitum species, Journal of Ethnopharmacology, 86, p63-67, 12686443.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/S0378-8741(03)00043-6]

-

Breitenbach, J., (2002), Melt extrusion: From process to drug delivery technology, European Journal of Pharmaceutics andBiopharmaceutics, 54, p107-117.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/s0939-6411(02)00061-9]

-

Breitkreutz, J., (1998), Prediction of intestinal drug absorption properties by three-dimensional solubility parameters, Pharmaceutical Research, 15, p1370-1375, 9755887.

[https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1011941319327]

-

Chiou, WL, Riegelman, S, (1971), Pharmaceutical application of solid dispersion systems, Journal of Pharmceutical Sciences, 60, p1281-1301, 4935981.

[https://doi.org/10.1002/jps.2600600902]

-

Chokshi, RJ, Sandhu, HK, lyer, RM, Shah, NH, Malick, AW, Zia, H, (2005), Characterization of physico-mechanical properties of indomethacin and polymers to assess their suitability for hotmelt extrusion processes as a means to manufacture solid dispersion/solution, Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences, 94, p2463-2474, 16200544.

[https://doi.org/10.1002/jps.20385]

-

Chuah, AM, Jacob, B, Jie, Z, Ramesh, S, Mandal, S, Puthan, JK, Deshpande, P, Vaidyanathan, VV, Gelling, RW, Patel, G, Das, T, Shreeram, S, (2014), Enhanced bioavailability and bio efficacy of an amorphous solid dispersion of curcumin, Food Chemistry, 156, p227-233, 24629962.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2014.01.108]

-

Cocchi, M, Foca, G, Lucisano, M, Marchetti, A, Paeani, MA, Tassi, L, Ulrici, A, (2004), Classification of cereal flours by chemometrie analysis of MIR spectra, Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, 52, p1062-1067, 14995098.

[https://doi.org/10.1021/jf034441o]

-

Correia, LP, Procopio, JVV, de Santana, CP, Santos, AFO, Cavalcante, HMM, Macedo, RO, (2011), Characterization of herbal medicine with different particle sizes using pyrolysis GC/MS, SEM, and thermal techniques, Journal of Thermal Analytical and Calorimetry, 111, p1691-1698.

[https://doi.org/10.1007/s10973-011-2129-x]

-

Crowley, MM, Zhang, F, Repka, MA, Thumma, S, Upadhye, SB, Battu, SK, McGinity, JW, Martin, C, (2007), Pharmaceutical applications of hot-melt extrusion: Part I, Drug Development and Industrial Pharmacy, 33, p909-926, 17891577.

[https://doi.org/10.1080/03639040701498759]

-

Deshmukh, K, Ahamed, MB, Deshmukh, RR, Pasha, SKK, Bhagat, PR, Chidambaram, K, (2017), 3-biopolymer composites with high dielectric performance: Interface engineering, Biopolymer Composites in Electronics, 2017, p27-128.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-809261-3.00003-6]

-

Gangurde, AB, Kundaikar, HS, Javeer, SD, Jaiswar, DR, Degani, MS, Amin, PD, (2015), Enhanced solubility and dissolution of curcumin by a hydrophilic polymer solid dispersion and its insilico molecular modeling studies, Journal of Drug Delivery Science and Technology, 29, p226-237.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jddst.2015.08.005]

-

Ghebremeskel, AN, Vemavarapu, C, Lodaya, M, (2007), Use of surfactants as plasticizers in preparing solid dispersion of pooly soluble API: Selection of polymer-surfactant combinations using solubility parameters and testing the processability, International Journal of Pharmaceutics, 328, p119-129, 16968659.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpharm.2006.08.010]

-

Ghimeray, AK, Sharma, P, Phoutaxay, P, Salitxay, T, Woo, SH, Park, SU, Park, CH, (2014), Far infrared irradiation alters total polyphenol, total flavonoid, antioxidant property and quercetin production in tartary buckwheat sprout powder, Journal of Cereal Science, 59, p167-172.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcs.2013.12.007]

-

Hagi, G, Hatami, A, (2010), Simultaneous quantification of flavonoids and phenolic acids in plant materials by a newly developed isocratic high-perfomance liquid chromatography approach, Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, 58, p10812-10816, 20919719.

[https://doi.org/10.1021/jf102175x]

-

Hintz, RJ, Johnson, KC, (1989), The effect of particle-size distribution on dissolution rate and oral absorption, International Journal of Pharmaceutics, 51, p9-17.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/0378-5173(89)90069-0]

-

Hulsmann, S, Backensfeld, T, Keitel, S, Bodmeier, R, (2000), Melt extrusion-an alternative method for enhancing the dissolution rate of 17 -estradiol hemihydrate, European Journal of Pharmaceutics and Biopharmaceutics, 49, p237-242, 10799815.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/S0939-6411(00)00077-1]

-

Janssens, S, Van den Mooter, G, (2009), Review: Physical chemistry of solid dispersions, Journal of Pharmacy andPharmacology, 61, p1571-1586.

[https://doi.org/10.1211/jpp.61.12.0001]

- Juri ić, V, Julson, JL, Krićka, T, Ćuric, D, Voća, N, Karunanithy, C, (2015), Effect of extrusion pretreatment on enzymatic hydrolysis of Miscanthus for the purpose of ethanol production, Journal of Agricultural Science, 7, p132-142.

-

Kadajji, VG, Betageri, GV, (2011), Water soluble polymers for pharmaceutical applications, Polymers, 3, p1972-2009.

[https://doi.org/10.3390/polym3041972]

-

Khaledi, MG, (1997), Micelles as separation media in highperformance liquid chromatography and high-performance capillary electrophoresis: Overview and perspective, Journal of Chromatography A, 780, p3-40.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/S0021-9673(97)00610-9]

-

Khoddami, A, Wilkes, MA, Roberts, TH, (2013), Techniques for analysis of plant phenolic compounds, Molecules, 18, p2328-2375, 23429347.

[https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules18022328]

-

Kim, KM, KIm, MJ, Kang, JS, (2009), Absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion of decursin and decursinol angelate from Angelica gigas Nakai, Journal of Microbiology and Biotechnology, 19, p1569-1572.

[https://doi.org/10.4014/jmb.0905.05028]

-

Kjoniksen, AL, Knudsen, KD, Nystrom, B, (2005), Phase separation and structural roperties of semidilute aqueous mixtures of ethyl(hydroxyethyl)cellulose and an ionic surfactant, European Polymer Journal, 41, p1954-1964.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eurpolymj.2005.03.011]

-

Lee, JJ, Park, JH, Lee, JY, Jeong, JY, Lee, SY, Yoon, IS, Kang, WS, Kim, DD, Cho, HJ, (2016), Omega-3 fatty acids incorporated colloidal systems for the delivery of Angelicagigas Nakai extract. Colloids and Surface B, Bioinerfaces, 140, p239-245, 26764107.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.colsurfb.2015.12.047]

-

Lee, SY, Lee, JJ, Nam, S, Kang, WS, Yoon, IS, Cho, HJ, (2017), a Fabrication of polymer matrix-free nanocomposites based on Angelica gigas Nakai extract and their application to brest cancer therapy, Colloids and Surface B: Biointerfaces, 159, p781-790, 28886514.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.colsurfb.2017.08.040]

-

Lee, SY, Nam, S, Choi, Y, Kim, M, Koo, JS, Chae, BJ, Kang, WS, Cho, HJ, (2017), b Fabrication and characterizations of hotmelt extruded nanocomposites based on zinc sulfate monohydrate and soluplus., Applied Sciences, 7, p902, http://www.mdpi.com/2076-3417/7/9/902/htm (cited by 2018 March 13).

[https://doi.org/10.3390/app7090902]

-

Leuner, C, Dressman, J, (2000), Improving drug solubility for oral delivery using solid dispersions, European Journal of Pharmaceutics and Biopharmaceutics, 50, p47-60, 10840192.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/S0939-6411(00)00076-X]

-

Li, B, Konecke, S, Wegiel, LA, Taylor, LA, Edgar, KJ, (2013), Both solubility and chemical stability of curcumin are enhanced by solid dispersion in cellulose derivative matrices, Carbohydrate Polymer, 98, p1108-1116, 23987452.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.carbpol.2013.07.017]

-

Maniruzzaman, M, Rana, MM, Boateng, JS, Motchell, JC, Douroumis, D, (2012), Dissolution enhancement of poorly water-soluble APIs processed by hot-melt extrusion using hydrophilic polymers, Drug Development and Industrial Pharmacy, 39, p218-227, 22452601.

[https://doi.org/10.3109/03639045.2012.670642]

-

Merisko-Liversidge, EM, Liversidge, GG, (2008), Drug nanoparticles: Formulating poorly water-soluble compounds, Toxicologic Pathology, 36, p43-48, 18337220.

[https://doi.org/10.1177/0192623307310946]

-

Miranda, A, Millan, M, Caraballo, I, (2007), Investigation of the influence of particle size on the excipient percolation thresholds of HPMC hydrophilic matrix tablets, Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences, 96, p2746-2756, 17506514.

[https://doi.org/10.1002/jps.20912]

-

Muller, RH, Jacobs, C, Kayser, O, (2001), Nanosuspensions as particulate drug formulations in therapy rationale for development and what we can expect for the future, Advanced Drug Delivery Reviews, 47, p3-19, 11251242.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/S0169-409X(00)00118-6]

-

Murdande, SB, Pikal, MJ, Shanker, RM, Bogner, RH, (2010), Solubility advantage of amorphous pharmaceuticals: II. Application of quantitative thermodynamic relationships for prediction of solubility enhancement in structurally diverse insoluble pharmaceuticals, Pharmaceutical Research, 27, p2704-2714, 20859662.

[https://doi.org/10.1007/s11095-010-0269-5]

-

Nam, S, Lee, JJ, Lee, SY, Jeong, JY, Kang, WS, Cho, HJ, (2017), Angelica gigas Nakai extract-loaded fast-dissolving nanofiber based on poly(vinyl alcohol) and soluplus for oral cancer therapy, International Journal of Pharmaceutics, 526, p225-234, 28478278.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpharm.2017.05.004]

-

Nam, S, Lee, SY, Kim, JJ, Kang, WS, Yoon, IS, (2018), Polydopamine-coated nanocomposites of Angelica gigas Nakai extract and their therapeutic potential for triple-negative breast cancer cells, Colloids and Surfaces B: Biointerfaces, 165, p74-82, 29454167.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.colsurfb.2018.02.014]

-

Newman, A, Knipp, G, Zografi, G, (2012), Assessing the performance of amorphous solid dispersion, Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences, 101, p1355-1377, 22213468.

[https://doi.org/10.1002/jps.23031]

-

Perriea, Y, Rades, T, (2010), Themed issue: Improve dissoltion, solubility and bioavailability of pooly soluble drugs, Journal of Pharmacy and Pharamacology, 62, p1517-1518, 21039536.

[https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2042-7158.2010.01199.x]

-

Piao, J, Lee, JY, Weon, JB, Ma, CJ, Ko, HJ, Kim, DD, Kang, WS, Cho, HJ, (2015), Angelica gigas Nakai and soluplus-based solid formulations prepared by hot-melting extrusion: Oral absorption enhancing and memory ameliorating effects, PloS ONE, 10, pe0124447, http://journals.plos.org/plosone/article/file?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0124447&type=printable (cited by 2018 March 3).

[https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0124447]

-

Qi, S, Belton, P, Nollenberger, K, Gryczke, A, Craig, DQM, (2011), Compositional analysis of low quantities of phase separation in hot-melt-extruded solid dispersions: A combined atomic force microscopy, photothermal fourier-transform infrared microspectroscopy, and localised thermal analysis approach, Pharmaceutical Reserach, 28, p2311-2326, 21607778.

[https://doi.org/10.1007/s11095-011-0461-2]

-

Qin, Y, Jiang, J, Zhao, L, Zhang, J, Wang, F, (2018), Applications of alginate as a functional food ingredient, Biopolymers for Food Design, 2018, p409-429.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-811449-0.00013-X]

-

Quinten, T, de Beer, T, Vervaet, C, Remon, JP, (2008), Evaluation of injection moulding as a pharmaceutical technology to produce matrix tablets, European Journal of Pharmaceutics and Biopharmaceutics, 71, p145-154, 18511248.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejpb.2008.02.025]

-

Repka, MA, Battu, SK, Upadhye, SB, Thumma, S, Crowley, MM, Zhang, F, Martin, C, McGinity, JW, (2007), Pharmaceutical applications of hot-melt extrusion: Part II, Drug Development and Industrial Pharmacy, 33, p1043-1057, 17963112.

[https://doi.org/10.1080/03639040701525627]

- Ryu, KS, Hong, ND, Kim, NJ, Kong, YY, (1990), Studies on the coumarin constituents of the root of Angelica gigas Nakaiisolation of decursinol angelate and assay of decursinol angelate and decursin, Korean Journal of Pharmacognosy, 21, p64-68.

-

Sekiguchi, K, Obi, N, (1961), Studies on absorption of eutectic mixture. I. Comparison of the behavior of eutectic mixture of sulfathiazole and that of ordinary sulfathiazole in man, Chemical and Pharmaceutical Bulletin, 9, p866-872.

[https://doi.org/10.1248/cpb.9.866]

-

Shit, SC, Shah, PM, (2014), Edible polymers: Challenges and opportunities, Journal of Polymers, https://www.hindawi.com/journals/jpol/2014/427259/abs/ (cited by 2018 May 11).

[https://doi.org/10.1155/2014/427259]

- Silverstein, RM, Webster, FX, Kiemle, DJ, (2006), Identifica o espectrom trica de compostos org nicos, LTC Editora, Rio de Janeiro. Brazil, p425-456.

- Singhal, S, Lohar, VK, Arora, V, (2011), Hot melt extrusion technique., WebmedCetral Pharmaceutical Sciences, 2, pWMC001459, http://www.webmedcentral.com/wmcpdf/Article_WMC001459.pdf (cited by 2018 April 20).

- Singleton, VL, Rossi, JA, (1965), Colorimetry of total phenolics with phosphomolybdic-phosphotungstic acid reagents, American Journal of Enology and Viticulture, 16, p144-458.

-

Szekeres, M, Tomb cz, E, (2012), Surface charge characterization of metal oxides by potentiometric acid-basetitration, revisited theory and experiment, Colloids and Surfaces A: Physicochemical and Engineering Aspects, 414, p302-313.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.colsurfa.2012.08.027]

- Tita, B, Fulias A Bandur, G, Marian, E, Tita, D., (2011), Compatibility study between ketoprofen and pharmaceutical excipients used in solid dosage forms, Journal of PharmacologyBiomedical Analysis, 56, p221-227, 21665404.

- Vervaet, C, Verhoeven, E, Quinten, T, Remon, JP, (2008), Hot melt extrusion and injection moulding as manufacturing tools for controlled release formulations, Dosis, 24, p119-123.

-

Wilson, M, Williams, MA, Jones, DS, Andrews, GP, (2012), Hot-melt extrusion technology and pharmaceutical application, Therapeutic Delivery, 3, p787-797, 22838073.

[https://doi.org/10.4155/tde.12.26]

-

Yang, JS, Xie, YJ, He, W, (2011), Research progress on chemical modification of alginate: A review, Carbohydrate Polymers, 84, p33-39.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.carbpol.2010.11.048]

- Yook, CS, (1990), Coloured Medicinal Plants of Korea, Academy Book, Seoul, Korea, p145.

-

Yoshioka, M, Hancock, BC, Zografi, G, (1994), The crystallization of indomethacin from the amorphous state below and above its glass transition temperature, Journal of Pharmacology, 83, p1700-1705, 7891297.

[https://doi.org/10.1002/jps.2600831211]

-

Yu, L, Haley, S, Perret, J, Harris, M., (2002), Antioxidant properties of hard winter wheat extracts, Food Chemistry, 78, p457-461.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/S0308-8146(02)00156-5]

- Zeleznak, K, Hoseney, R, (1987), The glass transition in starch, Cereal Chemistry, 64, p121-124.

-

Zia, KM, Zia, F, Zuber, M, Rehman, S, Ahmad, MN, (2015), Alginate based polyurethanes: A review of recent advances and perspective, International Journal of Biological Macromolecules, 79, p377-387, 25964178.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2015.04.076]