줄기세포 배양을 통한 들깻잎 로즈마린산 대량 생산 기반 기술 개발

This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/) which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Abstract

The objective of the present study is to establish a cambium-derived stem cell culture method for stable mass production of rosmarinic acid (RA) from Perilla leaves for industrialization.

Perilla frutescens leaves of the Bora variety were used as starting material. These leaves accumulated the highest levels of RA among the 32 Perilla varieties examined. Callus was successfully induced in solid MS medium containing 2.0 ㎎/ℓ 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid (2,4-D) and 0.05 ㎎/ℓ benzylaminopurine. Then, white, soft, and crushable stem cells were isolated using a microscope. RA was obtained at a concentration of 40.4 ± 1.4 ㎎/g after culturing callus stem cells in a quarter-strength MS liquid medium containing 0.5 ㎎/ℓ 2,4-D to produce RA in large quantities. To determine the properties of stem cells, we performed the catalase test. When hydrogen peroxide, a strong oxidizing chemical, was applied to stem cells, bubbles appeared almost immediately, demonstrating the antioxidant ability of these cells. In addition, microscopic examination revealed that these stem cells included a relatively large number of tiny vacuoles, whereas callus contained large vacuoles.

A cambium-derived stem cell culture method was developed. The method enables the production of RA from P. frutescens leaves in large, industrial-scale quantities.

Keywords:

Perilla frutescens, Callus Induction, Catalase Activity Test, Rosmarinic Acid, Stem Cell, Vacuoles서 언

들깨 (Perilla frutescens Britton var. crispa Deane)는 꿀풀과 (Lamiaceae)에 속하는 열대 아시아 원산의 일년생 초본식물이다 (Lee et al., 2011). 우리나라의 대표 유지작물 중 하나로 대한민국, 중국, 인도, 일본 등의 동아시아에서 주로 재배되고 있으며 종실용과 잎들깨로 구분된다 (Ahamed, 2019; Han et al., 2004). 들깻잎의 기능성 화합물에는 apigenin, luteolin, anthocyanin 등의 플라보노이드 성분, perillaldehyde, perillaketone 등의 휘발성 물질, caffeic acid, rosmarinic acid (RA), ferulic acid 등의 페놀 화합물 등으로 분류된다 (Yamazaki and Saito, 2006; Asif, 2012; Ahmed, 2019; Kim et al., 2021).

플라보노이드 성분은 식물에서 자연적으로 발생하는 항산화 활성을 지닌 페놀 그룹을 대표하는 화합물이다. 또한, 휘발성 물질은 다양한 방향성 식물 기관에서 추출된 이차대사산물로 항균, 항바이러스, 항암, 항산화 등과 같은 다양한 생리 활성을 갖는 것으로 알려져 있다 (Asif, 2012; Raut and Karuppayil, 2014).

최근 많은 식용 식물의 페놀 화합물은 식물 방어 기작에 중요한 주요 2차 대사산물로서 (Barros et al., 2011; Kim et al., 2013), 항산화 (Da Silvia et al., 1991)와 항암 작용 (Lee and Lee, 2008)에 대해 알려져 있으며 의학적 치료에도 매우 중요하다고 알려져 있다 (Lim et al., 2004).

특히 RA는 천연 항산화제로 노화 방지 및 혈관 건강 등에 관여한다고 알려져 있고 (Kim et al., 2019), 체내에서 생성되는 활성 산소를 제거하는 역할을 통해, 항산화, 항염증, 항균, 항바이러스, 항암, 항알러지 및 뇌세포 대사기능을 촉진해 학습 능력 향상 및 기억력 감퇴를 예방하고 스트레스를 줄여주는 효능 및 치매 예방 효과도 있다고 알려져 있다 (Parnham and Kesselring, 1985; Hong et al., 1986; Cho, 2003; Oh, 2003; Petersen and Simmonds, 2003; Sanbongi et al., 2004; Lee et al., 2008; Park et al., 2008; Ryu and Kim, 2008; Lee et al., 2009; Oh et al., 2011; Kim et al., 2021).

식물의 이차대사산물을 인공적으로 생산하기 위한 수단으로 생물반응기를 이용한 물질생산 방법이 널리 쓰인다 (Shohael et al., 2005; Park et al., 2008). 생물반응기를 이용하는 식물 세포배양은 기후적, 환경적 요건 등을 극복하여 지속적이며 안정적으로 생산할 수 있다는 장점이 있다 (Choi et al., 2002). 또한, 배양 조건들의 세심한 조작을 통해 특정 목표 화합물의 선별적인 합성을 할 수 있으며 생산수율을 극적으로 증가시킬 수도 있다 (Yun et al., 2012).

그러나, 식물세포 배양 시스템은 일반적으로 생산물 형성에 큰 변화를 보여 잠재적인 상업적 유용성을 제한하는 경우가 많다 (Ketchum et al., 1999). 이러한 단점을 보완하고자 식물 줄기세포 배양에 관심을 가지게 되었다 (Lee et al., 2010). 줄기세포는 선천적으로 미분화되어 있으며, 줄기와 뿌리 말단의 분열 조직, 도관의 형성층 등에 극미량으로 존재하며, 자가 재생산 (self-renewal) 능력을 통해 유전적 변이 없이 안정적인 장기배양이 가능하다고 알려져 있다 (Laux, 2003; Lee et al, 2010). 이러한 식물세포 배양 시스템이 상업화된 예로, 항암제인 파클리탁셀 및 인삼, 은행, 토마토 등에서 줄기세포 배양이 광범위한 유용성을 가지고 있음이 보고되었다 (Strobel et al., 1993; Yun et al., 2012).

그러나, 줄기세포의 특성을 경제성으로 연결하기 위해서는 아직도 미비한 단계로, 식품이나 의약품의 원료로서 사용 가능한 수준으로 대량 배양이 가능한 줄기세포 배양 방법의 개발 및 특성에 관한 연구가 더욱 필요하다.

따라서 본 연구에서 대표적 항산화 물질인 로즈마린산의 대량 생산을 위해 들깻잎 형성층 유래 줄기세포 배양 체계를 확립하고자 하였다.

재료 및 방법

1. 식물 재료

실험 재료는 32 개의 들깨 품종 중 로즈마린산 함량이 가장 높다고 보고된 (Lee et al., 2009) 보라 품종 (10.3 ㎎/g) 종자를 국립식량과학원 남부작물부 에서 제공받았다.

시료를 확보하기 위해 국립농업과학원 농업생명자원부 온실 내에서 종자를 화분에 파종하였고 약 초장이 30 ㎝ 정도일 때 중간 정도 크기의 잎을 채취하여 사용하였다.

2. 줄기세포 선발용 고체배양 호르몬 조건

캘러스 유도를 위한 보라 들깨의 재료 크기는 약 7 ㎝ 길이의 잎을 사용하였으며, 재료 소독은 70% 에탄올로 20 초간 침지 후 멸균 증류수로 3 회 수세, 차아염소산나트륨 2%에 4 분 1 회, 차아염소산나트륨 1%에 6 분씩, 2 회 살균 후 각각 멸균 증류수로 3 회 수세하였다. 잎은 엽맥을 중심으로 약 0.3 ㎝ × 0.3 ㎝ 정도의 정사각형으로 잘라 배지에 치상하였다.

배양 방법은 형성층을 분리하여 형성층으로부터 줄기세포 형태의 캘러스를 유도 (Lee et al., 2010) 하지 않고 먼저 캘러스를 유도한 후 줄기세포 특성을 가진 것만을 계속 분리하여 배양하는 방법을 사용하였다.

줄기세포 형태 캘러스 유도를 위한 배지는 MS 배지 (Murashige and Skoog, 1962)에 auxin류인 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid (2,4-D) 단독 첨가, 2,4-D와 cytokinin류인 benzylaminopurine (BAP), 그리고 2,4-D와 같은 auxin류인 α-naphthalene acetic acid (NAA)를 다양한 농도로 각각 조합하여 첨가하였다. 본 실험은 빠른 최적 조합 선발을 위해 모든 처리를 동시에 진행하였다.

2,4-D는 무처리, 0.01, 0.02, 0.05, 0.1, 0.2, 0.5, 1.0, 2.0, 3.0 ㎎/ℓ의 농도로 단독 처리하였고, 2,4-D와 BAP 조합은 2,4-D 0.01 ㎎/ℓ와 BAP 0.01, 0.1 ㎎/ℓ, 2,4-D 0.05 ㎎/ℓ와 BAP 0.005, 0.01, 0.05, 0.5 ㎎/ℓ, 그리고 2,4-D 2.0 ㎎/ℓ 와 BAP 0.05, 0.1, 1.0 ㎎/ℓ로 각각 조합 처리하였다.

또한, 2,4-D와 NAA 조합은 2,4-D 0.01 ㎎/ℓ와 NAA 0.001, 0.01, 0.1 ㎎/ℓ, 2,4-D 0.05 ㎎/ℓ와 NAA 0.005, 0.05, 0.5 ㎎/ℓ, 2,4-D 0.1 ㎎/ℓ와 NAA 0.01, 0.1, 0.5 ㎎/ℓ, 그리고 2,4-D 2.0 ㎎/ℓ와 NAA 0.1, 0.2, 0.5 ㎎/ℓ의 농도로 각각 조합 처리하였다.

탄소원은 3%의 sucrose, 경화제는 0.4% gelrite를 첨가한 후 pH 5.8로 조절하였으며, 배지는 petri-dish (100 ㎜ × 40 ㎜, SPL Life Sciences, Pocheon, Korea)에 100 ㎖ 씩 분주하였다. 배양 조건은 25 ± 1℃에서 8 - 10 주간 암배양을 실시하였다.

3. 줄기세포 분리 배양

캘러스가 형성된 후 줄기세포의 특징인 흰색을 띠며 부드럽고 뭉개지는 듯한 캘러스 (stem cell callus : SCC)만을 선별하여 3 주 간격으로, 12 주 이상 계대 배양하였다. 연노란색을 띠며 딱딱하고 분리가 되지 않은 캘러스 (non-stem cell callus : NSC)는 계대 배양 중 계속 걸러내었다.

4. 줄기세포 확인을 위한 catalase activity test

줄기세포가 환경적 스트레스에 강하다는 특성을 이용하여 (Lee et al., 2010), NSC와 선별한 SCC에 강력한 산화제인 과산화수소 (H2O2) 1 ㎖를 처리하여 기포 발생 속도, 양, 부위의 다소를 관찰하여 catalase activity를 측정하였다 (Arora et al., 2002).

5. 줄기세포 확인을 위한 전자현미경 transmission electron microscope (TEM) 관찰

줄기세포의 특성을 알아보기 위해 transmission electron microscope (TEM, LEO912AB, Carl Zeiss, Oberkohen, Germany)을 이용하여 줄기세포를 관찰하고 특정화하였으며 흰색을 띠는 부드러운 조직감의 SCC와 연한 노란색의 딱딱한 NSC의 세포적 외관 차이를 확인하였다.

각 세포의 관찰을 위한 고정을 위해 조직을 잘라 2 ㎖ 튜브에 Karnovsky,s 고정액 (paraformaldehyde 8%, glutaraaldehyde 25%, cacodylate buffer 0.2 M)에 넣고 4℃에서 12 시간에서 16 시간까지 침지 후, cacodylate buffer 0.05 M (cacodylic acid 0.05 M, pH 7.2로 조정)에 10 분씩 3 회 세척하였다. 재고정을 위해 1% osmic acid (osmium oxide 1g, cacodylate buffer 100 ㎖)에 침지 후 4℃에서 120 분 동안 처리한 후, 1차 증류수로 10 분씩, 3 회 세척하였다.

1차 염색을 위해 고정화된 세포는 0.5% uranyl acetate에 침지 후 4℃에서 12 시간에서 16 시간까지 전처리 하였고, 탈수를 위해 실온에서 에탄올을 농도별로 (50, 75, 90, 95, 100 %) 각 10 분씩 처리하였다. 치환을 위해 propylene oxide에 15 분씩, 2 번 처리하였다. embedding을 위해 propylene oxide와 Spurr (1 : 1) 용액에 120 분간 침지하고 다시 30 분간 교반하였으며, 5 분 동안 감압하여 치환을 용이하게 하였고, Spurr 용액에 담가 하루 동안 방치하여 처리하였다. hardening을 위해 Spurr 용액을 70℃에서 20 시간 동안 두어 시료를 굳혔다.

그 후 ultramicrotome (Leica ultracut UCT, Leica, Wetzlar, Germany)을 이용하여 75 ㎛의 두께로 박편 조제 후 TEM (field emission transmission electron microscope, JEM-2100F, JEOL, Akishima, Japan)으로 검경하였다.

6. 대량 생산을 위한 액체배양 조건

약 16 주간 고체배양하여 유도된 캘러스에서 현미경으로 SCC만을 분리, 로즈마린산의 대량 생산을 위해 새로운 배지에 SCC 1 g을 접종하여 액체배양을 실시하였다. 줄기세포 형태 캘러스 증식을 위한 액체 배지 조건은 MS와 1/4MS 배지에 각각 0.5, 1.0 ㎎/ℓ 2,4-D를 첨가하였다. 액체 배지는 1ℓ 삼각플라스크에 500 ㎖씩 분주하여 접종 후 25 ± 1℃에서 120 rpm으로 12 주 동안 암배양 상태에서 현탁배양하였다.

7. 줄기세포 유래 로즈마린산 정량 분석 (LC-MS/MS 분석)

NSC와 SCC를 대상으로 하여 로즈마린산의 정성· 정량 분석을 실시하였다. 2,4-D 0.5 ㎎/ℓ를 포함한 1/4MS 액체 배지에서 배양된 NSC와 SCC에서 액체 배지를 제거하고 캘러스만을 모아 동결건조 후 파우더로 준비하였다 (NSC: smaple 1, SCC: sample 2).

준비된 NSC와 SCC 동결건조 분말 5 ㎎에 메탄올 (MeOH) 5 ㎖를 첨가하고 30 초 동안 voltexing하여 추출하였고 상온에서 5 분 동안 초음파 (BRANSON 5210, BRANSON, Danbury, CT, USA)를 처리한 후 3,000 rpm, 10 분 동안 원심분리 (Centrifuge 5415R, eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany)하였으며 상등액을 0.45 ㎛ 필터 (Milles-HV, Merck Millipore Ltd, Tullagreen, Carrigtwohill, Co. Cork, Ireland)를 사용, 여과하여 HPLC 분석을 위한 시료로 사용하였다.

HPLC (HPLC 1200, Agillent Technologies, San Diego, CA, USA)분석은 1200 시리즈 HPLC 시스템으로 구성된 6460 삼중 사중 극자 질량 분석기 (QQQ 6460, Agillent Technologies, San Diego, CA, USA)를 사용하여 수행했다.

컬럼은 Proshell 120 EC-C18 (150 ㎜ × 3.0 ㎜, 2.7 ㎛, Agilent Technologies, San Diego, CA, USA)를 사용하였고 실온의 오븐 온도에서 분석을 수행하였다.

이동상 용매는 증류수에 희석한 0.1% 포름산 (용매 A)와 아세토니트릴에 희석한 0.1% 포름산 (용매 B)를 사용하였다. 용매 구배는 다음과 같은 조건에서 수행하였으며 (0 - 0.06 min, 10% B; 0.06 - 6.00 min, 98% B; 6.00 - 9.00 min, 98% B; 9.00 - 9.10 min, 10% B; and 9.10 - 15.00 min, 10% B), 유속은 0.3 mL/min으로 분석하였다. 모든 분석에서 분석 시료의 주입량은 2 ㎕로 고정하였다.

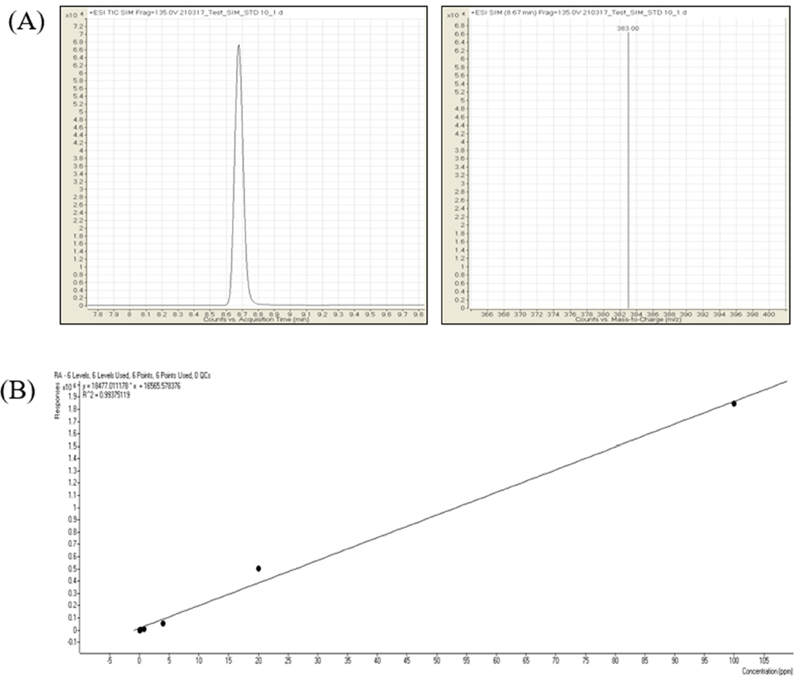

분석 조건은 3500V로 설정된 모세관 전압으로 단일 이온 모니터링 (Single ion monitoring, SIM)을 사용하였다. 이온화 방법으로는 전자분무 이온화(Electrospray ionization, ESI)로 positive ion mode에서 383 m/z [(360 + 23 (Na)) 전이를 목표로 분석하였다.

8. 통계분석

모든 실험은 3 회 이상 반복하여 평균 ± 표준편차로 나타내었고, 실험으로부터 얻은 결과는 SPSS 통계프로그램 (Statistical Package for the Social Science, ver. 12.0, SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA)을 이용하여 통계처리 하였다. 통계적 유의성 검정은 student’s t-test로 5% 수준에서 유의수준을 비교 검정하였다 (p < 0.05).

결과 및 고찰

1. 들깨 잎 유래 줄기세포 선발을 위한 고체배양 최적 조건 확립

들깻잎 절편은 치상한 지 1 주 후부터 캘러스가 형성되기 시작하였으며, 각 호르몬 처리 구에서 두 가지 형태의 캘러스를 관찰할 수 있었다. 첫 번째는 딱딱하며 분리가 되지 않고, 흰색, 연한 노란색 또는 노란색을 띠는 캘러스의 형태를 나타내었으며 (non-stem cell callus, NSC), 두 번째는 형태가 고정되어 있지는 않으나 부드럽고 쉽게 뭉개지며 분리가 잘 되는 특성을 나타내었다 (stem cell callus, SCC). 이후 추가적 실험을 통해 두 가지 형태의 캘러스 중 후자가 줄기세포임을 확인하였다 (Fig. 2).

식물조직배양에서 옥신 (auxin) 계열의 2,4-D는 거의 모든 식물의 캘러스 유도에 영향을 주는 식물호르몬으로 보고된 바 있어 (Baskaran and Raja, 2006; Tahir et al., 2011), 들깻잎에도 캘러스 유도를 위해 다양한 농도의 2,4-D를 처리하였다 (Table 1).

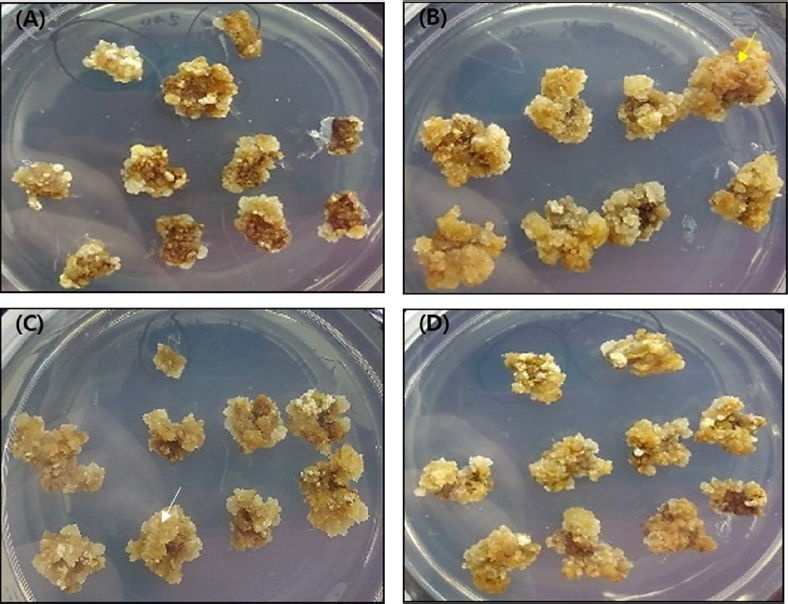

2,4-D 농도가 1.0 ㎎/ℓ 미만인 경우 딱딱한 형태의 NSC가 주로 관찰되었지만 (Fig. 1A), 1.0 ㎎/ℓ 이상, 특히 2.0 ㎎/ℓ를 첨가했을 때 줄기세포의 특징을 나타내는 SCC의 비율이 증가되어 부드러운 모양의 캘러스가 유도되었다 (Fig. 1B).

Callus induction of Perillafrutescensleaves on MS medium containing plant growth hormones.(A); 0.5 ㎎/ℓ of 2,4-D, (B); 2.0 ㎎/ℓ of 2,4-D, (C); 2.0 ㎎/ℓ of 2,4-D and 0.05 ㎎/ℓ of BAP, (D); 2.0 ㎎/ℓ of 2,4-D and 0.1 ㎎/ℓ of NAA. The yellow and white arrows indicated non-stem cell callus (NSC) and stem cell callus (SCC), respectively. MS solid media (Murashige and Skoog media including vitamin) were used for callus induction with different plant growth regulators. 2,4-D; 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid, BAP; 6-benzylaminopurine, NAA; α-naphthalene acetic acid

이러한 결과는 2,4-D의 처리 농도에 따라 유도되는 캘러스의 특징이 달라짐을 나타낸다고 할 수 있으며, 사탕수수 (Saccharum officinarum) 어린 잎의 캘러스 유도를 위한 2,4-D 농도가 0.0 ㎎/ℓ에서 4.0 ㎎/ℓ로 증가함에 따라 캘러스 형성률도 높아지며 연한 노란색의 치밀한 캘러스가 유도되었다고 보고된 연구와도 일치하였다 (Tahir et al., 2011).

또한, 들깻잎 (Perilla frutescens Britton var. crispa)에서 2,4-D 0.1 ㎎/ℓ 및 1.0 ㎎/ℓ 처리 시, 모두 부드럽고 부서지기 쉬운 캘러스의 특징을 나타냈으며 형성률도 높았다고 보고된 결과 (Tanimoto and Harada, 1980)와 유사하였고, 들깻잎의 캘러스 유도에 적절한 농도의 2,4-D가 필요하다는 것을 다시 확인할 수 있었다.

사이토키닌 (cytokinin)은 식물 분열 조직의 세포 분열을 촉진하므로 옥신과 함께 조직배양에 많이 이용 된다 (Su et al., 2011). 따라서, 본 실험에선 사이토키닌 계 호르몬의 영향을 살펴보기 위해 2,4-D 단독 첨가 결과 중 줄기세포의 특성을 가장 많이 포함한 처리구인 2,4-D 2.0 ㎎/ℓ로 고정한 후 다양한 농도의 BAP와 조합 처리하고 배양한 후 형성되는 캘러스 형성률 및 특성의 결과를 나타내었다 (Table 1).

2,4-D 2.0 ㎎/ℓ 와 BAP 0.05 ㎎/ℓ의 조합 처리구에서는 캘러스의 형성량도 많으면서 줄기세포의 특성을 가진 SCC의 비율도 높게 포함되어 있는 모습이 관찰되었다 (Fig 1B and 1C). 이는 2,4-D 2.0 ㎎/ℓ 단독 처리 시 캘러스의 형성량은 많았지만 SCC의 비율은 낮은 처리보다 더 나은 결과였다.

또한, 식물생장호르몬 무처리구인 MS 배지에서는 어떠한 반응도 나타나지 않았으며 BAP 농도가 0.1 ㎎/ℓ로 높아지면서 캘러스 형성량은 많았으나 SCC는 관찰되지 않았고 BAP의 조합 농도가 1.0 ㎎/ℓ의 수준이 되는 경우 오히려 캘러스 형성량이 급격히 억제되고 갈변되었으며 결국 괴사하는 결과를 얻었다.

따라서, 본 실험 결과는 2,4-D 2.0 ㎎/ℓ와 저농도의 BAP (0.05 ㎎/ℓ) 동시 처리가 SCC의 형성에 효과적임을 확인할 수 있었다. 이 결과는 쑥 (Artemisia princeps var. Orientalis)의 잎으로부터 캘러스 유도에 대한 저농도의 BAP의 영향은 크지 않으나, 2.0 ㎎/ℓ의 고농도로 첨가했을 경우는 오히려 캘러스 유도를 억제한다는 결과와 일치하였으며 (Shin et al., 2005), 만병초 (Rhododendron brachycarpum)의 잎 (Kwon et al., 2018)과 할미꽃 (Pulsatilla koreana Nakai) 유식물의 자엽 (Yoon et al., 2006)을 이용한 캘러스 유도에 있어 고농도의 2,4-D와 저농도의 BAP 처리가 적합하였다는 결과와도 유사하였다.

옥신 계열 호르몬의 상보적인 효과를 알아보기 위해 2.0 ㎎/ℓ의 2,4-D을 기준으로, 다양한 농도의 NAA를 조합 처리한 결과 2.0 ㎎/ℓ 농도의 2,4-D에 NAA를 0.1 ㎎/ℓ에서 0.5 ㎎/ℓ의 수준으로 조합 처리한 경우, 모든 조합 처리 구에서 줄기세포의 특징인 SCC가 관찰되었으며 캘러스 형성량도 증가하였다 (Table 1 and Fig. 1D).

이러한 결과는 포멜로 (Citrus grandis)의 잎 유래 캘러스 유도에 관한 옥신의 효과에서 2,4-D 농도가 NAA 농도보다 낮을 때 캘러스 형성률이 높지만 뿌리가 유도된다고 보고한 결과와 (Tao et al. 2002) 배치되는 것이었으며 따라서, 옥신의 상보적인 효과는 식물에 따라 차이가 있음을 확인할 수 있었다.

따라서 들깻잎 절편 유래 줄기세포 형태의 캘러스 유도 조건은 MS 배지에 2,4-D 2.0 ㎎/ℓ와 BAP 0.05 ㎎/ℓ 조합, 3%의 sucrose, 0.4% gelrite 그리고 암배양 처리가 최적 조건임을 확인하였다.

2. Catalase 테스트를 통한 줄기세포 확인

줄기세포가 환경적 스트레스에 저항성이 있는 특성을 고려하여, 강력한 산화제인 H2O2를 처리했을 때 catalase에 의해 물과 산소로 분해되어 기포가 빠르게 다량으로 발생하는 특성을 이용, 간편하게 줄기세포를 확인하는 방법으로 이용할 수 있다고 보고하였다 (Ransy et al., 2020)

이러한 산화 스트레스에 대한 식물세포 반응에는 대표적 항산화효소인 peroxidase 및 catalase가 중요한 역할을 하며, 특히 식물의 peroxisome에 존재하는 catalase는 free radicles의 생성 없이 산소 분자와 물로 분해되는 것을 촉매함으로써 H2O2의 독성 효과로부터 세포들을 보호하는 효과를 보인다고 보고된 바 있으며 (Arora et al., 2002), chrysoeriol-7-0-glucoside 대량 생산용 씀바귀 (Ixeridium dentatum) 배 발생 callus 유래 줄기세포를 이용한 기능성 물질 대량 생산에 대한 특허에서도 동일한 방법으로 캘러스와 구별되는 줄기세포를 확인, 보고하였다 (Park et al, 2023).

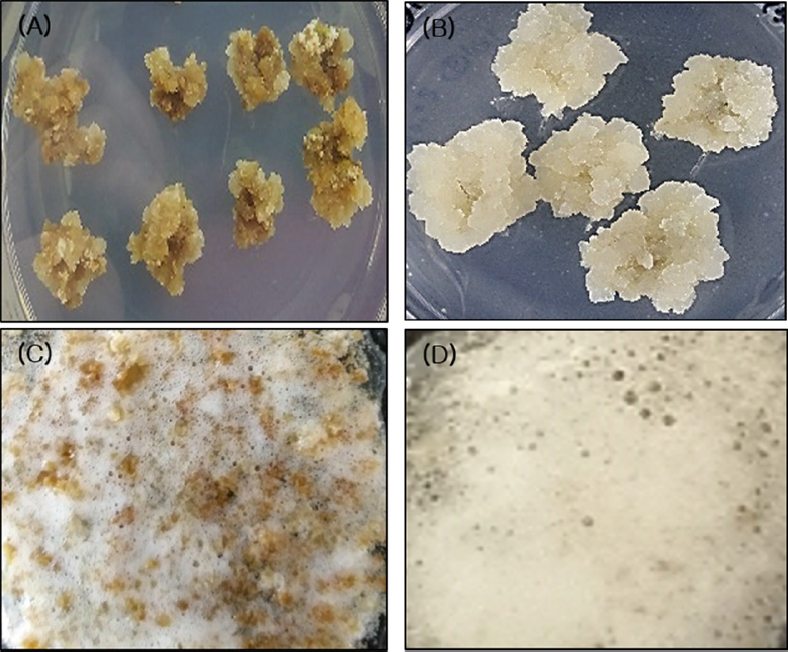

따라서, 본 실험의 들깻잎 유래 캘러스가 줄기세포에서 유래하였는지 알아보기 위해 H2O2를 첨가하여 caltase 활성을 조사한 결과, SCC와 NSC가 혼재되어있는 캘러스는 기포 발생 반응이 느리고 (Fig. 2A), 발생량도 적었으나 (Fig. 2B), 동일한 배지에 3 주 간격으로, 12 주 이상 계대 배양을 실시한 SCC 추정 캘러스는 catalase test 결과, 전체가 기포 발생이 빠르고 (Fig. 2C), 플레이트 전체가 기포로 뒤덮이는 모습이 관찰되어 catalase 활성이 높음을 확인할 수 있었다 (Fig. 2D).

Catalase test of NSC and SCC. For the catalase activity test, 1 ㎖ of H2O2 was dropped onto the callus, and bubbles were generated.The shape of 8 - 10 week old nonstem cell callus (NSC, A) and sub-cultured stem cell callus (SCC, B). Comparison of bubble generation between NSC (C) and SCC (D) after addition of H2O2.

3. 투과전자현미경 Transmission electron microscope (TEM) 관찰을 통한 줄기세포 특성

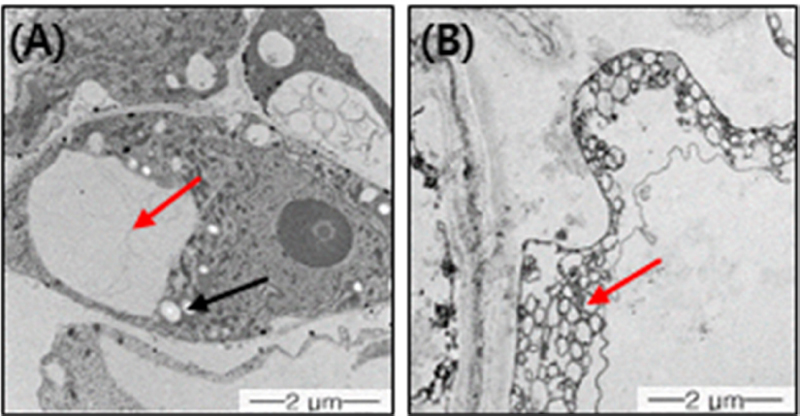

Catalase 활성 테스트로 구분된 SCC와 NSC를 투과전자현미경 관찰을 통해 세포 내 두 종류 캘러스의 차이를 확인하고자 하였다. 기포 발생이 늦으며 발생량이 적었던 NSC는 분화된 세포에서 흔히 관찰되는 커다란 액포가 존재 하였으나 (Lee et al., 2010; Yun et al., 2012) (Fig. 3A), 기포 발생이 빠르고 다량 발생한 SCC는 다수의 작은 액포로 이루어져 있음을 관찰할 수 있었으며, 액포가 매우 작아 NSC를 관찰할 때보다 배율을 높게 해서 관찰해야 했다 (Fig. 3B). 또한, 세포의 전체적인 모습이 정형화되지 않는 부정형 형태의 모습임을 관찰할 수 있었다.

Microscopic analysis of NSC and SCC. Because the cell sizes differed, the microscope was used to observe them at different magnifications (A; 5000 ×, B; 8000 ×).(A); non-stem cell callus (NSC) is composed of a large vacuole. (B); stem cell callus (SSC) possesses numerous and small vacuoles. Red and black arrows indicated vacuoles and starch, respectively.

위 결과는 현미경 관찰 시, 식물 줄기세포는 다수의 작은 액포를 포함하는 특징이 있고, 이에 반해 일반 캘러스의 세포는 커다란 액포로 이루어져 있다고 보고된 것과 일치 하였다 (Lee et al., 2010; Yun et al., 2012).

따라서, 본 실험에서 SCC 및 NSC 구별을 위해 이용한 catalase 활성 조사 및 전자현미경 방법이 효과적이고, 추후 줄기세포임을 판단할 수 있는 근거가 될 수 있다는 것을 확인할 수 있었다.

4. 기능성 물질 로즈마린산 대량 생산을 위한 최적의 액체배양 조건 확립

들깨 보라 품종 유래 줄기세포의 대량 생산을 위한 액체배양 시스템을 확립하고자 하였다.

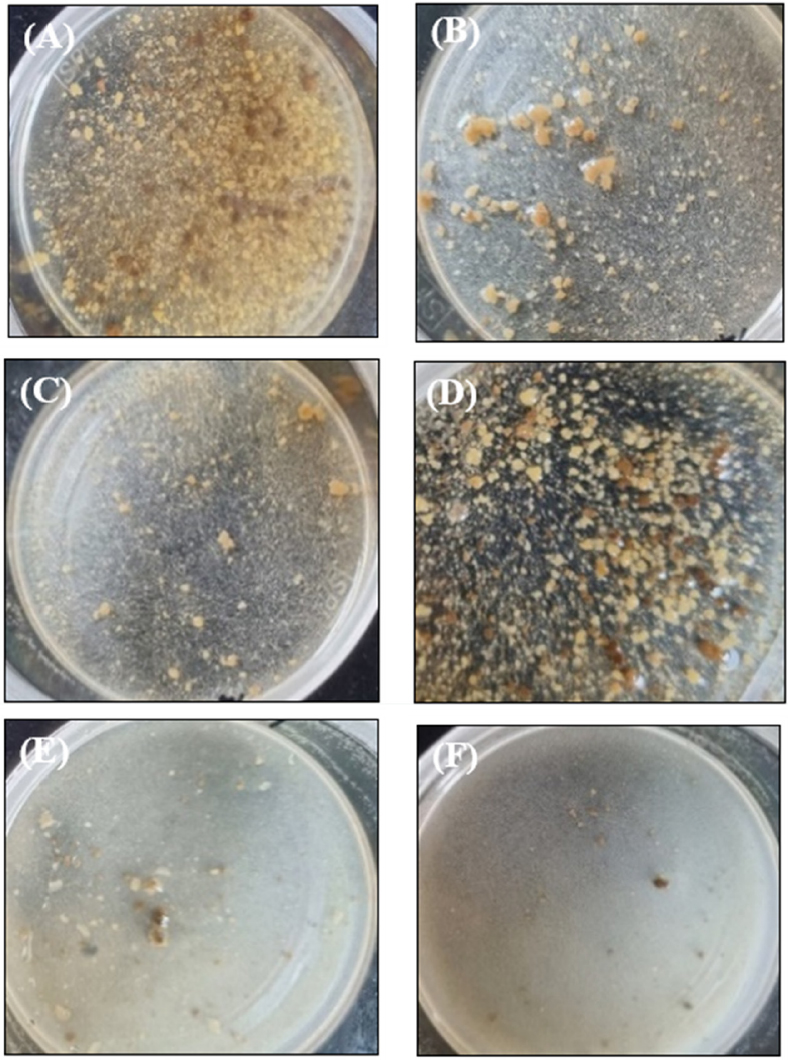

2,4-D를 첨가하지 않은 MS 액체 배지는 캘러스가 갈변되었으나 (Fig. 4A), 2,4-D를 0.5, 1.0 ㎎/ℓ의 수준으로 첨가한 MS 액체 배지에서 캘러스는 갈변되지 않고 증식도 잘 되었으나, 배양 기간이 지날수록, 줄기세포의 특성을 잃어버리는 것으로 보인다 (Fig. 4B and 4C).

Liquid culture for mass production of SSC using different media and plant growth regulators.Calluses were grown in MS liquid media with 0.0 (A), 0.5 (B), or 1.0 ㎎/ℓ (C) 2,4-D. 1/4 MS liquid media was used for callus culture with 0.0 (D), 0.5 (E), or 1.0 ㎎/ℓ (F) 2,4-D.

2,4-D를 첨가하지 않은 1/4MS 액체 배지에서 캘러스는 갈변이 되면서 뿌리 발생이 관찰된 반면 (Fig. 4D), 2,4-D를 0.5, 1.0 ㎎/ℓ의 수준으로 첨가한 1/4MS 액체 배지에서 SCC의 특징을 가장 잘 유지하면서 증식되는 것을 관찰할 수 있었다 (Fig. 4E and 4F).

본 실험 결과를 통해 2,4-D가 고체 배지뿐 아니라, 액체배양에서도 캘러스 형성과 생장에 효과 있음을 알 수 있었다. 또한, 액체배양을 위해선 MS 배지보다는 저농도의 1/4MS 배지가 적합함을 알 수 있었다.

캘러스는 배지의 성분이나 물리적, 화학적인 배양 조건에 따라 생장과 2차 대사산물 합성에 영향을 받기 때문에 배양 조건이 아주 중요하다 (Sakurai et al. 1997). 또한, 고체배양의 경우 캘러스나 재료들의 한 부분만이 배지의 표면에 닿게 되어 캘러스와 배지 사이에 설정된 영양분 구배에 대한 반응으로 성장반응의 불균형이 발생한다. 그러나 액체배양인 경우 배지의 움직임으로 gas 교환을 촉진하고 조직의 극성을 없애며 배지와 조직 표면의 영양 구배를 균등하게 하여 성장을 촉진한다 (Street et al., 1973).

또한, 식물 배양체를 액체 배지가 들어있는 생물반응기에서 배양할 때 고체 배지와 같은 조건으로 배양하면 배양체의 생장이 고체 배지에서와 같이 잘 이루어지지 않는데 그 이유는 액체 배지의 경우 고체 배지와 같은 높은 농도의 배지 성분이 내부로 들어가 세포들이 상해를 입게 되어 배양하기가 힘들어지므로 적정 농도의 액제 배지를 제조해야만 배양이 가능한데 이는 배지 농도를 낮추어주는 것이 가장 효율적이다 (Whang et al., 2009). 따라서 기능성 물질의 대량 생산을 위해서 단시간에 많은 양을 생산할 수 있는 액체배양을 이용하며 고체배양과의 배양 조건과 다르게 액체배양에서 배지의 농도 및 식물호르몬의 농도를 더 낮추어 조절하여야 한다.

들깻잎으로 부터 식물생장조절제 무첨가인 MS 액체 배지에서는 캘러스가 유도되지 않았고 2,4-D 및 kinetin 조합 처리한 MS 액체 배지에서 캘러스 유도에 좋은 결과를 나타냈다고 보고하였다 (Nabeta et al., 1983). 또한 들깻잎으로부터 캘러스를 유도 후 고체 배지와 동일한 2,4-D 1.0 ppm 및 kinetin 5.0 ppm 조합 처리한 MS 액체 배지에서 배양했을 때 성장률이 더 빨랐다고 하였다 (Sugisawa and Ohnishi, 1976). 이는 본 실험 결과와 유사하여 역시 호르몬 무첨가보다는 조합 처리에서도 2,4-D 첨가가 캘러스 성장에 효과가 있음을 알 수 있었다. 또한, 2,4-D를 단독 처리한 MS 배지 및 MS 농도를 낮춘 1/4MS 배지에서 배양한 결과와도 유사하여 캘러스를 더 빨리 생장하고 유지하는데 2.4-D가 필요함을 알 수 있었다.

솔나리 (Lilium cernuum KOMAROV) 인편을 2,4-D 1.0 ㎎/ℓ 첨가 및 호르몬 무첨가한 MS 농도별 액체 배지에서 배양한 결과 뿌리의 분화 및 생장은 식물생장조절제가 첨가되지 않은 1/4MS 배지에서 나타났으며 생장조절제가 처리되지 않은 액체 배지에서 캘러스 증식 없이 상당량의 캘러스가 활성을 잃었다고 보고하였다 (Kim et al., 2001). 본 실험 결과 역시 호르몬 무첨가인 MS 액체 배지에서는 거의 갈변되어 활성을 잃었으며 1/4MS 배지에서는 갈변이 되면서 뿌리가 형성되었다는 결과와 유사하였다.

괭이밥 (Oxalis reclilnata) 절간 유래 캘러스를 같은 호르몬 처리인 BA 및 NAA 조합 처리한 MS 액체 배지에서 유백색 캘러스 라인을 얻을 수 있었다 (Makunga et al., 1997). 본 실험에서는 2,4-D를 사용했을 때 줄기세포의 특징 중 하나인 흰색의 캘러스가 생장하여 auxin이라 할지라도 식물체 및 호르몬 종류에 따라 캘러스의 특징이 달라짐을 알 수 있었다. 호르몬 무첨가 MS, 1/4MS 배지에서는 캘러스가 갈변되었고, 2,4-D 0.5 ㎎/ℓ를 첨가한 1/4MS 배지에서는 줄기세포 형태의 캘러스가 갈변되지 않고 형태가 유지되며 증식되는 것을 확인하였다. 또한, 2,4-D 1.0 ㎎/ℓ 첨가한 MS, 1/4MS 배지에서는 줄기세포 형태의 캘러스가 증식되다가 어느 시기 이후 일반 캘러스로 변하며 줄기세포 형태를 잃었다. 따라서 들깻잎 줄기세포 형태의 캘러스를 액체배양으로 대량 생산을 하기 위해서는 1/4MS 배지에 2,4-D 0.5 ㎎/ℓ 첨가 배지 조성이 적정한 것으로 보인다.

본 실험 결과를 바탕으로 하여 SCC의 특성을 가장 잘 유지하면서 생장량이 증가했던 2,4-D 0.5 ㎎/ℓ를 첨가한 1/4MS 액체 배지 조건으로 생물반응기에 배양하여 캘러스의 대량 생산을 확인할 필요가 있을 것으로 판단된다.

5. 줄기세포 유래 로즈마린산 생합성 정성·정량 분석 (LC-MS/MS 분석)

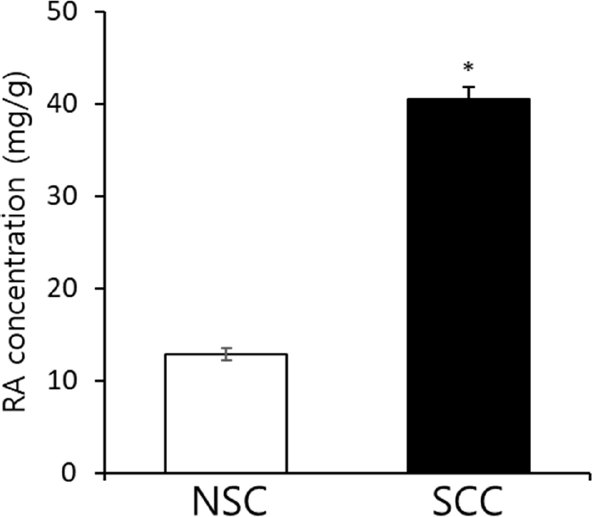

LC-MS/MS 분석을 통해 NSC와 SCC의 로즈마린산 함량을 측정하였다 (Fig. 6). SCC 추출물의 로즈마린산 함량은 40.4 ± 1.4 ㎎/g로 NSC 추출물의 함량 (12.9 ± 0.7 ㎎/g)보다 3 배 이상 높았다 (Fig. 6).

로즈마린산의 HPLC-MS 분석 결과 표준물질인 로즈마린산의 분자량은 36.31 g/㏖이며 분석 시 이온화 과정을 거치면서 분자량은 383.0 m/z이 되었다. 로즈마린산은 8.67 min일 때 383.0 분자량을 얻었으며 (Fig. 5A), 0.032 ppm - 100 ppm 범위로 로즈마린산을 정량하여 standard의 calibration curve를 구하였고 이때의 R2 값은 0.99375119로 신뢰도가 높았다 (Fig. 5B). 또한, LOD (limitation of detection, 검출한계)는 10.514 ㎎/ℓ이였고, LOQ (limitation of quantification,, 정량한계)는 34.695 ㎎/ℓ 값을 나타내었다 (Fig. 5).

HPLC-MS chromatogram of rosmarinic acid.(A); a peak of rosmarinic acid was detected at 8.67 min., 360.31 + 23 (Na) by HPLC-MS, (B); calibration curve of rosmarinic acid standard solution. A curve confirming the concentration of rosmarinic acid sustance by treating each from 0.031, 0.16, 0.8, 4, 20, 100 ppm.

Quantification of RA by LC-MS/MS analysis. RA in SCC is about three-fold higher than in NCC.Data are means ± SE (n = 3) and significant differences between non-stem cell callus (NSC) and stem cell callus (SCC) are indicated with asterisk by Student’s t-test (*p < 0.05).

이 결과는 로즈마린산의 대량 생산을 위해서는 줄기세포에서 유래한 캘러스 배양이 일반적인 캘러스 배양보다 효율적임을 나타낸다.

본 실험에서는 로즈마린산이 캘러스 액체 배지 배양 중 세포 바깥으로 분비되는지 알아보기 위해 배양용 액체 배지의 로즈마린산 함량을 분석하였을 때 검출이 되지 않았다. 따라서, SCC의 액체배양 시에도 로즈마린산은 세포 내에 여전히 존재함을 알 수 있었다.

위의 결과를 종합하면, 들깨 품종 보라의 잎 유래 줄기세포를 유도하기 위한 배지의 호르몬 처리는 2,4-D 2.0 ㎎/ℓ와 BAP 0.05 ㎎/ℓ, 로즈마린산 물질을 대량 생산하기 위한 액체배양은 2,4-D 0.5 ㎎/ℓ를 첨가한 1/4MS 배지가 가장 적합한 배양 체계임을 알 수 있었다.

본 연구를 통해 줄기세포 유래 기능성 물질인 로즈마린산을 액체배양 방법을 확립하였으며, 앞으로 대용량의 생물반응기를 이용한 대량 생산 가능성을 보임으로써, 추후 산업화를 위한 기반을 마련할 수 있을 것으로 생각된다. 또한, 향후 로즈마린산의 기능성 확인 및 다양한 기능성 작물들의 줄기세포 유도 및 대량 생산 방법 개발을 통해 식물 줄기세포의 산업적 생산에 관한 연구가 필요할 것으로 판단된다.

Acknowledgments

본 연구는 농촌진흥청에서 주관하는 들깨 품질 향상을 위한 항산화 강화 연구(과제번호: PJ014710101 )의 연구비 지원에 의해 이루어진 결과로 이에 감사드립니다. 또한, 로즈마린산 생합성 정량 분석을 위해 LC-MS/MS 분석을 해 주신 한국기초과학연구원(KBSI)에 감사드립니다.

References

-

Ahmed HM. (2019). Ethnomedicinal, phytochemical and pharma-cological investigations of Perilla frutescens(L.) Britt. Molecules. 24:102. https://www.mdpi.com/1420-3049/24/1/102, (cited by 2023 May 5).

[https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules24010102]

- Arora A, Sairam R and Srivastava G. (2002). Oxidative stress and antioxidative system in plants. Current Science. 82:1227-1238.

-

Asif M. (2011). Health effects of omega-3,6,9 fatty acids: Perilla frutescens is a good example of plant oils. Oriental Pharmacy and Experimental Medicine. 11:51-59.

[https://doi.org/10.1007/s13596-011-0002-x]

- Asif M. (2012). Phytochemical study of polyphenols in Perilla frutescens as an antioxidant. Avicenna Journal of Phytomedicine. 2:169-178.

-

Barros L, Duenas M, Ferreira ICFR, Maria Carvalho A and Santos-Buelga C. (2011). Use of HPLC-DAD-ESI/MS to profile phenolic compounds in edible wild greens from Porutugal. Food Chemistry. 127:169-173.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2011.01.009]

- Baskaran PB, Raja R and Jayabalan N. (2006). Development of an in vitro regeneration system in Sorghum[Sorghum bicholor(L.) Moench] using root transverse thin cell layers(tTCLs). Turkish Journal of Botany. 30:1-9.

- Cho MS. (2003). A study of intakes of vegetables in Korea. Journal of the Korean Society of Food Culture. 18:601-612.

- Choi HK, Son JS, Na GH, Hong SS and Song JY. (2004). Mass production of paclitaxel by plant cell culture. In Proceedings of the Korean Society of Plant Biotechnology Conference. p.27-30.

- Han HS, Park JH, Choi HJ, Son JH, Kim YH, Kim S and Choi C. (2004). Biochemical analysis and physiological activity of perilla leaves. Korean Journal of Food Culture. 19:94-105.

- Hong YP, Kim SY and Choi WY. (1986). Postharvest changes in quality and biochemical components of perilla leaves. Korean Journal of Food Science and Technology. 18:255-258.

-

Ketchum REB, Ginson DM, Croteau RB and Shuler ML. (1999). The kinetics of taxoid accumulation in cell suspension cultures of Taxus following elicitaion with methyl jasmonates. Biotechnology and Bioengineering. 62:97-105.

[https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1097-0290(19990105)62:1<97::AID-BIT11>3.0.CO;2-C]

-

Kim DJ, Assefa AD, Jeong YA, Lee JE, Lee MC, Lee HS, Rhee JH and Sung JS. (2019). Variation in fatty acid composition, caffeic and rosmarinic acid content, and antioxidant activity of Perilla accessions. Korean Jounal of Medicinal Crop Science. 27:96-107.

[https://doi.org/10.7783/KJMCS.2019.27.2.96]

- Kim HE, Yun HR and Heo JB. (2021). Comparative analysis of functional compounds in Perilla futescens at different stages and growth times. Jounal of Life Science. 31:5511-5519.

- Kim HK, Lim JD, Hyun TK, Lee HY, Lee JH and Yu CY. (2001). In vitro culture and acclimation of regenerated plants of Lilium cernuum KOMAROV. Korean Journal of Medicinal Crop Science. 9:310-317.

-

Kim SJ, Cho AR and Han J. (2013). Antioxidant and antimicrobial activities of leafy green vegetable extracts and their applications to meat product preservation. Food Control. 29:112-120.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodcont.2012.05.060]

- Kwon DY, An CH and Song JH. (2018). Effect of plant growth regulators on callus induction of Rhododendron brachycarpum. Proceedings of Korean Journal of Medicinal Crop Science. 26:91-91.

-

Laux T. (2003). The stem cell concept in plants; a matter of debate. Cell. 113:281-283.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/S0092-8674(03)00312-X]

-

Lee EK, Jin YW, Park JH, Yoo YM, Hong SM, Amir R, Yan Z, Kwon EJ, Elfick A, Tomlinson S, Halbritter F, Waibel T, Yun BW and Loake GJ. (2010). Cultured cambial meristematic cells as a source of plant natural products. Nature biotechnology. 28:1213-1217.

[https://doi.org/10.1038/nbt.1693]

- Lee HH and Lee SY. (2008). Cytotoxic and antioxidant effects of Taraxacum coreanum Nakai. and T. officinale WEB. extracts. Korean Journal of Medicinal Crop Science. 16:79-85.

- Lee HS, Lee HA, Hong CO, Yang SY, Hong SY, Park SY, Lee HJ and Lee KW. (2009). Quantification of caffeic acid and rosmarinic acid and antioxidant activities of hot-water extracts from leaves of Perilla frutescens. Korean Journal of Food Science Technology. 41:302-306.

- Lee JH, Baek IY, Kang NS, Jung CS, Lee MH, Park KY and Ha TJ. (2009). Optimization of extraction conditions and comparison of rosmarinic and caffeic acids from leaves of Perilla frutescens varieties. Korean Journal of Food Science Biotechnology. 18:793-798.

-

Lee JS, Jung ES, Koh JS, Kim YS, Park DH. (2008). Effect of rosmarinic acid on atopic dermatitis. Journal of Dermatology. 35:768-771.

[https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1346-8138.2008.00565.x]

- Lee MH, Jung CS, Oh KW, Park CB, Kim DG, Choi JK and Nam SY. (2011). A new perilla cultivar for edible seed ‘Dayu’ with high oil content. Korean Journal of Breeding Science. 43:616-619.

- Lim JD, Yun SJ, Lee SJ and Chung IM. (2004). Comparison of resveratrol contents in medicinal plants. Korean Journal of Medicinal Crop Science. 12:163-170.

-

Makunga NP, Van Staden, Cress WA. (1997). The effect of light and 2,4-D on anthocyanin production in Oxalis reclilnata callus. Plant Growth Regulation. 23: 153-158.

[https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1005966927813]

-

Murashige T and Skoog F. (1962). A revised medium for rapid growth bioassays with tobacco tissue cultures. Plant physiology. 15:473-497.

[https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1399-3054.1962.tb08052.x]

-

Nabeta K, Ohinishi Y, Hirose T and Sugisawa H. (1983). Monoterperne biosynthesis by callus tissues and suspension cells from Perilla species. Phytochemistry. 22:423-425.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/0031-9422(83)83016-7]

-

Oh HA, Park CS, Ahn HJ, Park YS and Kim HM. (2011). Effect of Perilla frutescens var. acuta Kudo and rosmarinic acid on allergic inflammatory reactions. Experimental Biology and Medicine. 236:99-106.

[https://doi.org/10.1258/ebm.2010.010252]

-

Oh SI and Lee MS. (2003). Screening for antioxidative and antimutagenic capacities in 7 common vegetables taken by Korean. Journal of the Korean Sociery of Food Science and Nutrition. 32:1344-1350.

[https://doi.org/10.3746/jkfn.2003.32.8.1344]

- Park CH, Yu CY, Kim DW, Cho HK, Park KS, Seo JS, Ahn SK and Chang BH. (1994). Plant regeneration of Bupleurum spp. through somatic tissue culture. Korean Journal of Medicinal Crop Science. 2:60-66.

- Park JS, Lee SH, Kim SY, Kim MA, Lee KR, Lee JH, Lee SK, Choi HJ, Lee HW, Seo JW and Sweong GH. (2023). Method of culturing Ixeridium dentatum embryogenic callus for mass production of chrysoeriol-7-0-glucoside. Korea. Patent. 10-2580993.

- Park SU, Uddin MR, Xu H, Kim YK and Lee SY. (2008). Biotechnological applications for roxmarinic acid production in plant. African Journal of Biotechnology. 7:4959-4965.

-

Parnham MJ and Kesselring K. (1985) Rosmarinic acid. Drugs of the Future. 10:756-757.

[https://doi.org/10.1358/dof.1985.010.09.71743]

-

Petersen M, and Simmonds MSJ. (2003). Rosmarinic acid. Phytochemistry. 62:121-125.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/S0031-9422(02)00513-7]

-

Ransy C, Vaz C, Lombes A, and Bouillaud F. (2020). Use of H2O2 to cause oxidative stress, the catalase issue. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 21:9149. https://www.mdpi.com/1422-0067/21/23/9149, (cited by 2023 November 8).

[https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms21239149]

-

Raut JS, and Karuppayil SM. (2014). A status review on the medicinal properties of essential oils. Industrial Crops Products. 62:250-264.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indcrop.2014.05.055]

-

Ricardo da Silva JM, Darmon N, Fernandez Y and Mitjavila S. (1991). Oxigen free radical scavenger capacity in aqueous models of different procyanidins from grape seeds. Journal of Agricultural Food Chemistry. 39:1549-1552.

[https://doi.org/10.1021/jf00009a002]

- Ryu HS and Kim HS. (2008). Studies on the effects of water extract from mixture of pine needles, Sedum sarmentosum bunge, hijkiaorme, buckwheat, and perilla leaves on the immune function activation. Korean Journal of Food and Nutrition. 21:269-274.

-

Sakurai M, Ozeki Y and Mori T.(1997). Induction of anthocyanin accumulation in rose suspension-cultured cells by conditioned medium of strawberry suspension cultures. Plant Cell Tissue Organ Culture. 50:211-214.

[https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1005946828703]

-

Sanbongi C, Takano H, Osakabe N, Sasa N, Natsume, Yanagisawa R, Inoue K, Sadakane K, Ichinosw, T and Yoshikawa T. (2004). Romarinic acid in perilla extract inhibits allegric inflammation induced by mite allergen, in mouse model. Clinical and Experimental Allergy. 34:971-977.

[https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2222.2004.01979.x]

- Shin DH, In JG, Yu SR and Choi KS. (2005). Investigation of medicinal substances from in vitro cultured cells and leaves of Artemisia princeps var. Orientalis. Korean Journal of Medicinal Crop Science. 13:69-76.

-

Shohael AM, Chakrabarty D, Yu KW, Gahn EJ and Pael KY. (2005). Application of bioreactor system for large-scale production of Eleutherococcus sessiliflorus somatic embryos in an air-lift bioreactor and production of eleutherisides. Journal of biotechnology.120:228-236.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbiotec.2005.06.010]

- Street HE, Aitchson PA, Butcher DN, Cocking EC, Evans PK, Ingram DS, King PJ, Reinert J, Sunderland N and Yeoman MM. (1973). Plant tissue and cell culture. Chapter 3 Tissue (callus) cultures techniques. University of California Press, Berkly and Los Angeles, California. 44-46.

-

Strobel GA, Stierle A, and Hess WM. (1993). Taxol formation in yew-Taxus. Plant Science. 92:1-12.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/0168-9452(93)90060-D]

-

Su YH, Liu YB, and Zhang XS. (2011). Auxin-cytokinin interaction regulates meristem development. Molecular Plant. 4:616-625.

[https://doi.org/10.1093/mp/ssr007]

-

Sugisawa H and Ohnishi Y. (1976). Isolation and identification of monoterpenes from cultured cells of Perilla plant. Agricultural and Biological Chemistry. 40:231-232.

[https://doi.org/10.1080/00021369.1976.10862026]

- Tahir SM, Victor K and Abdulkakir S. (2011). The effect of 2,4-dichlorophenoxy acetic acid(2,4-D) concentration on callus induction in Sugacane(Saccharum officinarum). Nigerian Journal of Basic and Applied Sciences. 19:213-217.

-

Tanimoto S and Harada H. (1980). Hormonal control of morphogenesis in leaf explants of Perilla frutescens Britton var. crispa Decaisne f. virdi-crispa Makino. Annals of Botany. 45:321-327.

[https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.aob.a085827]

-

Tao H, Shaolin P, Gaofeng D, Lanying Z and Gengguang L. (2002). Plant regeneration from leaf-derived callus in Citrus grandis(pummelo): Effects of auxins in callus induction medium. Plant cell, Tissue and Organ culture. 69:141-146.

[https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1015223701161]

-

Whang SS, Koo JH, Choi K, Park KW, Kang KW, Choi EG and Kim JW. (2009). Mass production of the seedlings of Dendrobium moniliforme using bioreactor culture. Journal of Plant Biotechnology. 36:392-396.

[https://doi.org/10.5010/JPB.2009.36.4.392]

- Yamazaki M and Saito K. (2006). Isolation and chracterization of anthocyanin 5-O-glucosyltransferase in Perilla frutescens var. Crispa by differential display, Differential Display Methods and Protocol. 317:255-266.

- Yoon ES, Kwon HK and Cho YY. (2006). Effects of plant growth regulation on adventitious root formation of Pulsatilla koreana Nakai. Korea Journal of Medicinal Crop Science. 14:225-228.

-

Yun BY, Yan ZJ, AMIR R, Hong SM, Jin YW, Lee EK and Loake GJ. (2012). Plant natural products: history, limitations and potential of cambial meristematic cells. Biotechnology and Genetic Engineering Reviews. 28:47-60.

[https://doi.org/10.5661/bger-28-47]