국내 유통 감초의 글리시리진 함량 및 약리적 문제에 관한 고찰

This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/) which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Abstract

Scarcity of wild licorice, which is most commonly used in oriental medicine, has led to an increase in the use of various other licorice species. Diversification of licorice species can affect the quality, safety, and standardization of food and medicine; therefore, it is crucial to verify and evaluate their major pharmacological components.

In this study, we collected licorice produced and distributed in various regions of Asia, including Korea, and compared the content of glycyrrhizin. The average glycyrrhizin content of wild licorice produced in China (Yangoe), Uzbekistan, Kyrgyzstan, and Kazakhstan was 3.2%, 5.5%, 5.5%, and 5.3%, respectively. In contrast, the average glycyrrhizin content of cultivated licorice from Xinjiang, China and Jecheon, Korea was 4.8% and 0.8%, respectively. The glycyrrhizin content of each licorice slice ranged from 1.0% to 12.4%. Wild licorice, in particular, had a high glycyrrhizin content and variation. In addition to pharmacological effects, glycyrrhizin has various side effects; therefore, the quality of wild licorice, which has been traditionally regarded as good, needs to be re-evaluated.

In terms of the stability of food and pharmaceutical raw materials, licorice with uniformity and appropriate content of glycyrrhizin is more effective in controlling and utilizing the pharmacology than licorice with considerably high glycyrrhizin content. To this end, it is crucial to shift production from wild licorice collection to cultivated licorice and develop related cultivation technologies.

Keywords:

Licorice, Glycyrrhiza uralensis Fisch., G. glabra L., G. korshinskyi Grig., Glycyrrhizin서 언

감초는 한방에서 가장 빈번하게 쓰이는 한약재이다 (MOHW, 2001). 세계적으로 자생하는 감초 분류군은 약 20여종 정도가 있으나 한방 문화권인 동아시아에서 주로 이용되는 한약재 감초 기원식물은 2 종 - 3 종으로 나라별 차이가 있다 (Dilfuza et al., 2016; Karkanis et al., 2016).

우리나라와 중국의 약전에는 만주감초 (Glycyrrhiza uralensis Fisch.), 광과감초 (G. glabra L.), 창과감초 (G. inflata Batal.) 3 종이 공통으로 등재되어 있고 (Choi, 2015), 최근 우리나라는 신감초 (G. korshinskyi Grig.)를 추가하여 총 4 종이 등재되었다. 일본약전에는 만주감초와 광과감초 2 종만 등재되어있다 (Choi, 2015). 이중 만주감초는 한국을 비롯한 동아시아 국가에서 예전부터 이용해왔던 종이고, 광과감초와 창과감초는 만주감초가 부족하게 되면서 현대에 와서 이용하게 된 종이다. 창과감초는 실제 국내 유통 빈도는 낮은 편이다.

만주감초는 중국, 몽골, 러시아 등에 주로 분포하고 있으며, 광과감초는 우즈베키스탄, 키르기스스탄 등 중앙아시아, 유럽에 주로 분포하고 있다. 광과감초는 국내시장에 늦게 출현하였음에도 불구하고 가격이 상대적으로 저렴하여 최근 이용 및 유통량이 만주감초보다 훨씬 많아졌다.

감초는 현대에 이르기까지 주로 자연채취에 의존해 왔으나 한약재뿐만 아니라 식품 및 산업 소재로 활용되어 이용량이 크게 증가하자 원산지 국가들에서 야생감초 남획이 사회문제로 대두되기 시작하였다 (Kobayashi et al., 2012; Marui et al., 2014; Furukawa et al., 2015). 이는 감초가 반건조지역 (Semi-arid zone)에서 자생하는 식물인데, 야생감초의 남획으로 인해 사막화를 촉진할 수 있기 때문이다 (Tuvshintogtokh et al., 2013).

이에 따라 몽골, 중국 등 감초 자생지 국가들은 야생채취에 대한 강력한 억제 정책을 취하고 있고, 광과감초를 생산하는 우즈베키스탄 등에서도 채취하는 만큼 복원할 수 있도록 생산자들을 유도하고 있다 (RDA, 2020). 야생 감초의 공급량이 줄어들자 대량 수요국인 중국에서는 부족분을 재배 감초로 대체하려는 노력을 지속해 왔다. 한국에서도 1990년대부터 본격적인 재배를 시도하여 2021년 기준 65 농가에서 연간 약 216 톤을 생산하고 있다 (MAFRA, 2022).

감초를 비롯해 많은 약초들의 본격적인 재배가 시작된 것은 비교적 현대에 들어와서이다. 자연채취 방식으로는 시장 수요량을 감당하기 어렵고 효율성도 떨어져 생산방식이 변경되었을 것으로 추정된다. 수 천 년 전부터 작물화 과정을 거친 식량 작물에 비하면 대단히 늦었지만 감초 역시 이러한 과정을 거쳐 가고 있는 중이다.

감초의 작물화는 단순히 생산과정만 변경된 것이 아니라 결과물에도 변화를 가져왔다. 특히 야생채취 감초에서 더 큰 비중을 차지하던 지하경은 재배과정에서 대부분 배제된다. 감초는 이제 과거에 비해 종적으로 다양화되었을 뿐만 아니라 주요 이용 부위마저 지하경에서 뿌리로 전환되는 과도기에 있다 (Table 5). 이러한 변화는 유통 약재의 약리적인 변화를 수반하므로 감초를 식품 및 의약품으로 이용하는 사람들에게도 상당한 영향을 미칠 수 있는 사안이다. 이에 따라 현재 유통되고 있는 여러 종류의 감초들에 대한 생산방식이나 그로 인한 약리적인 품질 차이, 안전성 등에 대한 기초적인 평가와 검토가 필요한 시점이다.

본 연구에서는 이를 위해 서울 제기동의 약령시장에서 유통중인 감초들을 대상으로 각각 원산지 및 생산방식별로 수집하여 대표적인 약리 성분인 glycyrrhizin 함량을 비교 분석하였다. 특히 유통 감초종의 다양성이 품목별 세부적인 품질 차이를 가져올 수 있음을 확인하기 위하여 복수의 시료군이 아닌 1 개의 시료군내에서 개별 절편을 비교 분석하였으므로 원산지별 특성을 대표하는 데에는 다소 한계가 있음을 밝힌다.

또한 이러한 다양한 감초들이 실제 식품 및 의약품으로 사용되었을 때 발생할 수 있는 문제들에 관한 고찰을 통해 감초를 어떤 방식으로 생산하고 이용해야 하는지에 관한 의견을 제시하고자 하였다.

재료 및 방법

1. 연구재료

시험에 사용된 감초의 시료는 2017년 8월경 서울 경동시장에서 여러 약재상을 통해 600 g 단위로 비닐로 포장된 것을 구입하였으며, 세부내용은 Table 1과 같다.

유통량이 가장 많은 감초인 중국 및 우즈베키스탄을 포함해 국내 제천 산까지 대부분의 유통 감초 원산지가 포함되도록 하였으며 약재의 크기도 가능한 한 통일하였다. 야생 감초는 중국 양외산, 우즈베키스탄산, 키르기스스탄산, 카자흐스탄산을 이용하였고, 재배 감초는 중국 신강산과 한국 제천산을 이용하였다. 광과감초는 아직 상업적으로 유통될 만큼 재배되는 경우가 거의 없어서 재배 감초 수집 대상에서 제외하였다.

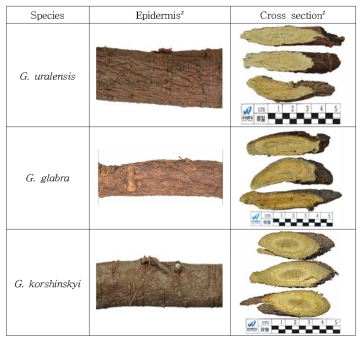

감초종 동정은 Kim 등 (2019)과 대한민국약전 (MFDS, 2014)을 기준으로 분류하였으며, 판매상의 유통 이력에 대한 의견을 참고하여 종합 판정하였다 (Table 2, Fig. 1).

Morphological characteristics of the epidermis and cross section of licorice species.zKorea Institute of Oriental Medicine (2015), Kim et al. (2019).

재배 또는 야생에 대한 판정은 현지의 주요 생산방식, 시료 표피의 무늬 패턴, 판매상의 유통 이력 의견 등을 종합하여 판정하였다. 특히 시료 표피의 무늬와 관련해서는 재배감초는 주로 뿌리로만 이루어지고, 야생감초는 지하경의 비율이 뿌리 보다 더 높은 점을 참고하여 각각의 패턴 및 비율 등을 분석하여 판정하였다.

의료처방을 위하여 감초가 사용될 때에는 보통 600 g 단위의 소포장에서 소량의 필요량만 취하게 되므로, 만일 감초의 포장 단위나 절편마다 품질 편차가 클 경우에는 동일한 약리 성분 함량의 반복적인 투약을 기대하기 어려울 수 있다. 이에 따라 본 시험에서는 소포장 내의 감초 절편 간의 glycyrrhizin 함량의 균일성을 확인할 목적으로 각 감초 1 봉지에서 절편 50 개씩을 취하여 각각 분석에 사용하였다.

또한 한 봉지 내에서도 각 감초 절편별 시료의 크기를 균일하게 맞추기 위하여 통상적인 유통 감초 규격인 1 호 (근두부 직경 1.3 ㎝ - 1.9 ㎝)에 해당하는 것만 버니어아캘리퍼스로 측정하여 선별하였다 (Park et al., 2003). 단 중국 양외 감초의 경우 1 봉지에 1 호의 크기에 해당하는 절편 수가 부족하여 2호 (근두부 직경 1.0 ㎝ - 1.3 ㎝) 감초를 일부 사용하였다.

2. 성분분석

감초의 glycyrrhizin 분석은 대한민국약전 (이하 약전) 제 11 개정 의약품각조 제 2 부에 규정의 약전 기준 분석법과 관련 문헌을 참고하여 분석하였다 (MFDS, 2014; Kim et al., 2020).

선별된 감초 절편은 분쇄하여 분말화하였다. 분말화된 시료 100 ㎎에 80% MeOH 10 ㎖을 가한 후, 파라 필름으로 밀봉하여 15 분 동안 3 회 초음파 추출한다. 얻어진 상등액을 여과용 멤브레인 필터 (PTFE, 0.45 ㎛)로 여과하여 시험 용액으로 사용하였다.

분석 조건은 Table 3과 같으며 glycyrrhizin 표준품은 코아사이언스 (Seoul, Korea)에서 구입하여 사용하였다 (Fig. 2).

3. 원산지 정보조사

원산지에 대한 정보는 관련 논문 및 보고서 등 선행연구 자료를 이용하였다. 감초의 성분함량 및 품질은 현지 생산이력과 관련성이 높을 것으로 여겨지므로 원산지별 환경이나 종특성, 현황 등 관련 정보를 포함하여 고찰하였다

4. 통계분석

연구 결과의 통계분석은 SAS Program (SAS Enterprise Guide 4.3, SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA)을 이용하였다. 각 실험의 결과값은 평균 ± 표준편차 (Means ± SD) 나타냈으며, 각 처리구간의 유의적 차이는 Duncan’s Multiple Range Test (DMRT) 방법을 사용하여 5% 수준에서 검증하였다 (p < 0.05).

결과 및 고찰

1. 유통 야생 감초 특성

중국 양외감초는 한방에서 오랜기간 동안 사용해온 감초 (G. uralensis)로 외관 품질 및 약성이 가장 우수한 것으로 알려져 국내 유통 가격이 가장 높은 편에 속한다 (Table 1). 본 연구에서 분석된 양외감초 중 11점 (22%)은 국내 약전의 글리시리진 기준인 2.5%를 충족하지 않았다. 평균 함량은 약 3.2%였으며, 최소 1.1%에서 최대 약 6.0% 정도의 함량을 보였다 (Table 4). 한약학적 처방에서 한 번의 처방을 위해 약 2 g - 8 g 정도를 사용한다고 가정할 경우 무작위로 추출했을 때의 평균 glycyrrhizin 함량 추정치는 대체로 약전 기준인 2.5% 이상을 충족할 것으로 추정된다.

양외 (梁外)는 중국의 내몽고 동북에서 서쪽으로 영하의 중간에 위치한 지역을 가리키는 것으로 추정되는데, 이 지역을 중심으로 위쪽의 몽골과 아래쪽의 감숙성 등 건조지대는 만주 감초의 원산지로 유명한 지역들이다 (MFDS, 2009). 몽골의 경우 특히 남부에 만주감초 군락지가 집중 분포하였으나 현재는 남획과 몽골 정부의 야생감초 채취 금지로 거의 생산되지 않고 있다 (Kobayashi et al., 2012; Tuvshintogtokh et al., 2013; Marui et al., 2014; Furukawa et al., 2015). 이에 따라 양외감초 원초는 내몽골 등 중국에서 대부분 생산되는 것으로 추정된다.

우즈베키스탄산 감초는 유사종들이 전혀 섞이지 않은 100% 광과감초 (G. glabra)로만 구성되었다 (Table 4). Glycyrrhizin 평균함량은 5.5%, 최대함량 10.8%로, 양외감초 (G. uralensis)에 비해 상대적으로 높게 평가되었다. 국내 약전기준인 2.5% 미만의 시료는 1 점 (2%)이었다 (Table 4). 약리 성분만을 품질평가의 기준으로 한다면 만주감초 (G. uralensis)보다 더 우수하다고 할 수 있으나 시중 가격은 가장 저렴한 편이며 (Table 1), 식품, 의약품, 화장품 소재 등 다양한 용도로 활용되고 있다.

우즈베키스탄산 감초는 카라칼파크스탄 자치주 (Republic of Karakalpakstan)에 있는 누쿠스 (Nukus) 지역에서 주로 생산되는데, 수확 후 공정과제에서 건조와 절단만 하는 만주감초 (G. uralensis)와 달리 스팀으로 쪄서 절단하기 때문에 비교적 복잡한 가공과정을 거친다 (RDA, 2020).

키르기스스탄산 감초는 만주감초 (G. uralensis)가 17%, 광과감초 (G. glabra)가 9%, 신감초 (G. korshinskyi)가 74%로 구성되었다 (Table 4). 신감초 (G. korshinskyi)는 만주감초 (G. uralensis)와 광과감초 (G. glabra)의 중간 정도의 형태적이고 유전적인 특성을 보이는 종이다. 우즈베키스탄산 감초 (G. glabra)와 마찬가지로 glycyrrhizin 함량이 매우 높았다. Glycyrrhizin 함랑은 연구 시료 중 2.5% 미만이 2 점 (4%)에 불과했으며, 대부분 glycyrrhizin 함량이 5.0% 이상이었다. 최대 함량은 9.3%였으며 평균 함량은 우즈베키스탄산 감초와 유사한 약 5.5%로 확인되었다 (Table 4).

키르기스스탄산 감초의 생산 및 유통량은 우즈베키스탄산감초에 비하면 적은 편이다. 키르기스스탄산 감초의 주요 분포지는 이식쿨 (Issvk-kul) 지역이 유명한데, 국내 제약사와 지자체 등에서 현지 감초와는 다른 종인 만주감초를 이용해 현지 재배를 시도했던 곳이기도 하다 (MCST, 2020). 이 지역은 비교적 기온이 낮은 곳에 속하여 감초의 성장이 더디다 보니 상업성이 떨어져 현재는 농장이 폐쇄된 것으로 알려져 있다. 그러나 현지인들의 야생감초 수확은 지속되고 있으며 중국 등을 거쳐 한국으로까지 유통되고 있다 (RDA, 2020).

카자흐스탄산 감초의 glycyrrhizin 함량 분포는 평균 5.3%였으며 최대 함량은 12.4%였다 (Table 4). 연구 시료 중 glycyrrhizin 함량이 2.5%에 미치지 못하는 것은 2 점 (4%)에 불과해 매우 높은 함량을 보였다.

카자흐스탄산 감초의 시료를 동정한 결과, 만주감초 (G. uralensis)가 확인되지 않았으며, 광과감초 (G. glabra)가 71%, 신감초 (G. korshinskyi)가 29%로 확인되었다 (Table 4). 그러나 카자흐스탄 지역은 문헌상 만주감초와 광과감초가 모두 분포하는 곳이기도 하다 (Hayashi et al., 2003a; Hayashi et al., 2003b). 또한 카자흐스탄산 감초는 여러 종이 혼합되어 유통되는 것으로 알려져 있는데, 그중에서 광과감초 (G. glabra) 종과 외형이 비슷한 것은 우즈베키스탄산 감초와 마찬가지로 시중 가격이 만주감초에 비해 저렴한 편이다. 현지에서는 정확한 감초 종명 대신에 근피색을 보고 홍피, 흑피 등으로 구분하는데 홍피는 만주감초로 흑피는 광과감초로 추정되며, 색깔 구분이 모호한 근피색들은 만주감초와 광과감초의 교잡된 기원종인 신감초가 섞여 있는 것으로 판단된다 (RDA, 2020). 야생감초는 자생지의 환경도 다양하지만 대부분 지하경과 뿌리가 섞여 있기때문에 절편의 색이나 형태적 특성만 보고 종을 판별하기는 어려움이 있다.

2. 유통 재배 감초 특성

신강감초의 시료는 만주감초 (G. uralensis)가 29%, 광과감초 (G. glabra)가 19%, 신감초 (G. korshinskyi)가 52% 포함되어 있어 종적 구성은 양외 감초와 비슷하였다 (Table 4). 대표적인 재배 감초인 중국 신강감초의 glycyrrhizin 평균 함량은 약 4.8%였으며 최대 함량은 9.1%에 달했으나 다른 감초들에 비하면 비교적 균일한 특성을 갖추고 있었다 (Table 4).

Glycyrrhizin 함량은 야생 광과감초 (G. glabra)보다는 낮았으며 양외감초보다 높았다. 연구 시료 중 glycyrrhizin 함량이 2.5%에 미치지 못하는 것은 6% (4/50 점)으로 나타났다. 감초는 대부분 재배와 종자 생산이 분리되어 있다. 충분한 종자가 맺히려면 최소 5년생 이상이 되어야 하기 때문에 재배과정에서 종자까지 수확하여 이용하는 경우는 드물다 (RDA, 2020). 이러한 비효율성으로 인해 신강의 재배 농가들도 대부분 육성된 품종을 이용하지 않고 내몽골, 감숙성 등지에서 채취한 야생감초 종자를 구입하여 이용하는 것으로 보고된 바 있다(RDA, 2020). 따라서 양외감초와 신강감초는 같은 만주감초 (G. uralensis) 종자에서 유래한 것으로 추정된다.

재배 감초인 신강감초가 연생이 훨씬 오래된 야생 양외감초보다 glycyrrhizin 함량이 높은 것은 이례적이다. 여러 연구에서 감초의 연생이 오래될수록 glycyrrhizin 함량이 대체로 조금씩 증가하는 경향이 있는 것으로 판단하고 있기 때문이다(Kim et al., 2019; Yamamoto et al., 2002; Yamamoto et al., 2003).

두 감초는 glycyrrhizin 함량 이외에도 많은 차이점들을 나타낸다. 형태적으로 볼 때 양외감초는 분질이 많고 신강감초는 육질이 더 단단한 특징이 있다 (MFDS, 2012; KIOM, 2015). 생산지마다 어느 정도 비율의 차이가 있겠지만 야생감초는 약 60% - 70% 정도가 지하경이고 나머지 30% - 40% 정도가 뿌리로 구성된다. 재배감초는 중국이나 한국 모두 재배과정에서 수량성을 높이기 위해 지하경 발생을 억제하기 때문에 거의 100% 뿌리로만 이루어져 있으므로 부위의 구성에 차이가 있다 (Table 5). 한국, 중국, 일본의 약전에는 지하경과 뿌리를 모두 사용할 수 있도록 명시되어있다 (Choi, 2015). 생산과정에서도 이를 별도로 구분하는 경우는 거의 없으며 부위에 상관없이 크기에 따라서 구분하는 것이 일반적이다. 아직까지 지하경과 뿌리를 구분하거나 각각의 생산과정을 추적하여 연구한 사례는 드물어 더 많은 연구가 필요할 것으로 판단된다.

국내 제천감초는 만주감초 (G. uralensis)가 7%, 광과감초(G. glabra)가 8%, 신감초 (G. korshinskyi)가 85%로 구성되어 있어, 신감초 (G. korshinskyi)가 많은 키르기즈스탄산 감초와 종적 분포가 유사하다 (Table 4). 국내 제천감초는 glycyrrhizin 함량이 평균 0.8%로, 약전 기준인 2.5%에 충족하는 절편은 없었다 (Table 4). 부분적으로 제천 감초의 glycyrrhizin 함량 부족은 선행연구 결과와 같이 짧은 재배기간과 우리나라의 고온다습한 기후환경으로 인한 조기낙엽 등과 관련이 있는 것으로 보인다 (Kim et al., 2019; Yamamoto et al., 2002; Yamamoto et al., 2003).

제천감초는 대개 1 년생 모종을 구입하여 이식한 후 다시 1 년간 재배한 후 출하를 하는 경우가 보통이라 시중에 유통되는 감초는 대부분 2 년생에 불과하여 5 년 내외인 신강감초에 비하면 연령이 짧은 편이다. 또한 감초 뿌리의 부피 생장은 2 년차에 가장 크게 나타나 상대적으로 함량이 가장 떨어지는 연령대에서 출하는 하는 것도 원인이 될 수 있을 것으로 판단된다 (Kim et al., 2020; RDA, 2020). 향후 국내산 감초를 의약품으로 사용하기 위해선 육종 및 재배기술 개발을 통해 glycyrrhizin 함량을 약전 기준치 (2.5%) 수준으로 증대하는 연구가 지속적으로 필요할 것으로 판단된다.

현재 유통되고 있는 감초들은 종적 다양성 이외에도 번식 방법이나 발달 특성, 생육환경 등에 있어서 많은 차이가 있다. 종자로 번식한 재배 감초는 지상부 및 뇌두와 뿌리가 일직선으로 연결되어 단독으로 자라지만 지하경으로 번식한 야생감초들은 지상부와 주근이 직접 연결되어 있지 않고, 발달된 지하경을 매개로 하여 비대칭으로 자란다 (RDA, 2020). 몽골 등의 야생 감초 군락 반경은 최대 수 ㎞에 이르는 경우도 있다 (Tuvshintogtokh et al., 2013). 지역적으로 보자면, 양외감초와 신강감초는 모두 위도가 높고 강우량이 적은 반사막 지역의 알칼리성 토양에서 자라는 반면 제천감초는 위도가 낮고 강우량이 많은 몬순기후로 환경적인 차이도 크다 (Table 5, Kobayashi et al., 2012; Marui et al., 2014; Furukawa et al., 2015).

3. Glycyrrhizin 과용 문제에 관한 고찰

위와 같이 감초의 glycyrrhizin 함량이 생산지와 감초종, 재배 유무 등에 따라 매우 다양하다는 사실은 단일한 감초를 이용하던 이전 시대와는 약재의 품질이 크게 달라졌음을 확인시켜 준다. 야생 양외감초는 현지 국가에서 불법 채취에 의존해야 할 정도로 생산이 어려워졌고 유통량도 현대의 시장 수요량을 충족하기에는 다소 부족하다 (Kobayashi et al., 2012; Marui et al., 2014; Furukawa et al., 2015).

감초의 glycyrrhizin 성분은 약리적 효과 이외에도 과다 섭취할 경우 고혈압, 저칼륨증, 부종 등 다양한 증상이 보고되어 있어, 적당량을 사용하는 것이 중요하다 (Table 6, Olukoga et al., 2000; Armanini et al., 2002).

본 연구에서 밝혀진 바대로 유통 감초들의 glycyrrhizin 함량은 지나치게 높거나 범위가 넓다. 따라서 의약품으로 사용시 정량화가 쉽지 않다. 동일한 양을 사용하여도 감초의 종류나 절편의 선택에 따라 glycyrrhizin 함량이 크게 달라질 수밖에 없다. 식품으로 이용할 경우 대량으로 혼합하여 평균화 되므로 균일성 문제는 일부 해소될 수도 있겠지만 과용 우려는 여전히 존재한다. 미국의 식품의약국 (FDA, Food and Drug Administration)에서도 과용방지를 위해 식품에 사용되는 감초유래 glycyrrhizin 함량의 최대치를 제한하고 있다 (Omar et al., 2012). 가령, 주류에는 0.1%, 음료는 0.15%, 허브와 조미료는 0.15% 등으로 최대 허용량을 규정하고 있다 (Table 7). 이는 glycyrrhizin 함량을 높이는 데에만 집중해온 한국, 중국, 일본 등의 경우와는 매우 대조적이라 할 수 있다.

이러한 상황들을 고려해 볼 때, 약리 성분이 높은 약재를 우수한 약재로 평가하는 국내시장과 식품 및 의료계의 인식 전환이 필요하다. 특히 ‘지표성분’의 의미에 관한 오해가 가장 많은데, 이것은 동의보감 등의 의서에서 지칭하는 약효를 나타내는 성분이 아니라 감초 한약재의 품질관리 측면으로 이해하는 것이 바람직하다. 따라서 함량이 많다고 해서 더 좋은 효능을 나타낸다고 볼 수는 없다 (Hong et al., 2007).

대한민국약전에는 glycyrrhizin 함량을 ‘2.5% 이상’으로 하여 하한선만 정하고 상한선은 제한이 없다 (MFDS, 2014). 약효는 불확실하고 부작용은 뚜렷하다면 glycyrrhizin 함량을 필요 이상으로 높여야 할 이유는 없을 것으로 판단되며, 약물과용을 방지하기 위해 일본, 중국 등과 같이 2% 정도로 하향조정하는 것도 고려해볼 필요가 있을 것으로 생각된다 (Choi, 2015).

현대의학의 개념이 정착되면서 생약의 품질기준에 대한 인식도 변화하고 있다. 과거에는 약성이 높은 약재나 특정 지역에서 생산되는 도지약재 (道地藥材, authentic herbs)를 선호하였다면 현대에 와서는 치료제로서 정량화, 표준화가 가능한지가 더 중요한 기준이 되어가고 있다. 표준화된 원료 생산이 가능해야 약리적 성분들의 투입량을 예측하는 데에도 유리하며, 환자나 소비자들의 건강을 위해서도 더 바람직하기 때문이다.

다양한 감초의 원료 표준화는 균일성이 확보된 품종을 이용하고 재배법을 통일하는 것이 목표를 이룰 수 있는 가장 확실한 방법이므로, 국내에서는 체계화된 품종육성과 표준재배법이 필요할 것으로 판단된다.

Acknowledgments

본 연구는 농촌진흥청 연구사업(과제번호: PJ014371052023) 의 지원에 의해 이루어진 결과로 이에 감사드립니다.

References

-

Armanini D, Fiore C, Mattarello MJ, Bielenberg J and Palermo M. (2002). History of the endocrine effects of licorice. Experimental and Clinical Endocrinology and Diabetes. 110:257-261.

[https://doi.org/10.1055/s-2002-34587]

- Bramont C, Lestradet C, Godart L, Faivre R and Narboni G. (1985). Cerebral vascular accident caused by alcohol-free licorice. La Presse Médicale. 14:746.

-

Cartier A, Malo J and Labrecque M. (2002). Occupational asthma due to liquorice roots. Allergy. 57:863.

[https://doi.org/10.1034/j.1398-9995.2002.23575_6.x]

- Choi GY. (2015). A comparative study on standards of Korean herbal medicines in the pharmacopoeias of Northeast-Asian countries(4) Liquorice. Korean Herbal Medicine Information. 3:17-26.

-

Dobbins KR and Saul RF. (2000). Transient visual loss after licorice ingestion. Journal of Neuro-opthalmology. 20:38-41.

[https://doi.org/10.1097/00041327-200020010-00013]

-

Egamberdieva D, Li L, Lindstöm K and Räsänen LA. (2016). A synergistic interaction between salt-tolerant Pseudomonas and Mesorhizobium strains improves growth and symbiotic performance of liquorice(Glycyrrhiza uralensis Fish.) under salt stress. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology. 100:2829-2841.

[https://doi.org/10.1007/s00253-015-7147-3]

-

Fraunfelder FW. (2004). Ocular side effects from herbal medicines and nutritional supplements. American Journal of Ophthalmology. 138:639-647.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajo.2004.04.072]

- Furukawa Z, Yasufuku N, Omine K, Marui A, Kameoka R, Tuvshintogtokh I, Mandakh B, Bat-Enerel B and Yeruult Y. (2015). Settings and geo-environmental conditions of developed greening soil materials(GSM) for cultivating licorice(Glycyrrhiza uralensis Fisch.) in Mongolian arid region. Journal of Arid Land Studies. 25:105-108.

-

Hall RC and Clemett RS. (2004). Central retinal vein occlusion associated with liquorice ingestion. Clinical and Experimental Ophthalmology. 32:341.

[https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1442-9071.2004.00830.x]

-

Harada T, Ohtaki E, Misu K, Sumiyoshi T and Hosoda S. (2002). Congestive heart failure caused by digitalis toxicity in an elderly man taking a licorice0containing Chinese herbal laxative. Cardiology 98:218.

[https://doi.org/10.1159/000067316]

-

Hayashi H, Hattori S, Inoue K, Sarsenbaev K, Ito M and Honda G. (2003a). Field survey of Glycyrrhiza plants in Central Asia(1). Characterization of G. uralensis, G. glabra and the putative intermediate collected in Kazakhstan. Biological and Pharmaceutical Bulletin. 26:867-871.

[https://doi.org/10.1248/bpb.26.867]

-

Hayashi H, Zhang SL, Nakaizumi T, shimura K, Yamaguchi M, Inoue K, Sarsenbaev K, Ito M and Honda G. (2003b). Field survey of Glycyrrhiza plant in Central Asia(2). Characterization of phenolics and their variation in the leaves of Glycyrrhiza plants collected in Kazakhstan. Chemical and Pharmaceutical Bulletin. 51:1147-1152.

[https://doi.org/10.1248/cpb.51.1147]

- Hong ND and Kim NJ. (2007). Quality control of herbal medicines. Shinilbooks. Seoul, Korea. p.87.

-

Karkanis A, Martins N, Petropoulos SA and Ferreira ICFR. (2016). Phytochemical composition, health effects, and crop management of liquorice(Glycyrrhiza glabra L.): A medicinal plant. Food Reviews International. 34:182-203.

[https://doi.org/10.1080/87559129.2016.1261300]

-

Kent UM, Aviram M, Rosenblat M and Hollenberg PF. (2002). The licorice root derived isoflavan glabridin inhibits the activities of human cytochrome P450S 3A4, 2B6 and 2C9. Drug Metabolism and Disposition. 30:709-715.

[https://doi.org/10.1124/dmd.30.6.709]

-

Kim YI, Lee JH, An TJ, Lee ES, Park WT, Kim YG and Chang JK. (2020). Study on the characteristics of growth, yield, and pharmacological composition of a new Glycyrrhiza variety licorice ‘Wongam(Glycyrrhiza glabra × Glycyrrhiza uralensis)’ in temperature gradient tunnel and suitable cultivation area of Korean. Horticultural Science and Technology. 38:44-55.

[https://doi.org/10.7235/HORT.20200005]

-

Kim YI, Lee JH, An TJ, Lee ES, Park WT, Kim YG and Chang JK. (2019). Study on the characteristics of growth, yield, and pharmacological composition of licorice(Glycyrrhiza uralensis Fisch.) in a temperature gradient tunnel. Korean Journal of Medicinal Crop Science. 27:322-329.

[https://doi.org/10.7783/KJMCS.2019.27.5.322]

- Kobayashi T, Shinkai A, Yasufuku N, Omine K, Marui A and Nagaruchi T. (2012). Field surveys of soil conditions in steppe of northeastern Mongolia. Journal of Arid Land Studies. 22:25-28.

- Korea Institute of Oriental Medicine(KIOM). (2015). Korean medicinal materials. Korea Institute of Oriental Medicine. Dejeon, Korea. p.8-15.

- Marui A, Kotera A, Furukawa Z, Yasufuku N, Omine K, Nagano T, Tuvshintogtokh I and Mandakh B. (2014). Monitoring the growing environment of wild licorice with analysis of satellite data at a semi-arid area in Mongolia. Journal of Arid Land Studies. 24:199-202.

- Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs(MAFRA). (2022). 2021 Production data of industrial crops. Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs. Sejong, Korea. p.6.

- Ministry of Culture, Sports and Tourism(MCST). (2020). Licorice grows better in Korea than in central Asia and China. Ministry of Culture, Sports and Tourism. Sejong, Korea. http://www.korea.kr, (cited by 2023 Jan 22).

- Ministry of Food and Drug Safety(MFDS). (2009). Chinese herbal medicine production information. Ministry of Food and Drug Safety. Seoul, Korea. p.1-256.

- Ministry of Food and Drug Safety(MFDS). (2012). The Korean pharmacopoeia. (11th eds.). Monographs. Ministry of Food and Drug Safety. Seoul, Korea. p.1321.

- Ministry of Food and Drug Safety(MFDS). (2014). The Korean Pharmacopoeia (11th eds.). The MFDS notification. No. 2014-194. Ministry of Food and Drug Safety. Seoul, Korea. p.1-328.

- Ministry of Health and Welfare(MOHW). (2001). A study on the consumption pattern and pricing structure of major oriental medicines in Korea. Ministry of Health and Welfare. Gwacheon, Korea. p.103.

-

Olukoga A and Donaldson D. (2000). Liquorice and its health implications. The Journal of the Royal Society for the Promotion of Health. 120:83-89.

[https://doi.org/10.1177/146642400012000203]

-

Omar HR, Komarova I, El-Ghonemi M, Fathy A, Rashad R, Abdelmalak HD, Yerramadha MR, Ali Y, Helal E and Camporesi EM. (2012). Licorice abuse: Time to send a warning message. Therapeutic Advances in Endocrinology and Metabolism. 3:125-138.

[https://doi.org/10.1177/2042018812454322]

- Park CG, Yu HS, Park CH, Sung JS, Park HW and Seong NS. (2003). Development of cultural practices in Glycyrrhiza uralensis Fisch. Crop Research Bulletin. 4:1-17.

- Rural Development Administration(RDA). (2020). Study on cultivation environment and production impact assessment of licorice according to climate conditions. Rural Development Administration. Jeonju, Korea. p.1-137.

-

Russo S, Mastropasqua M, Mosetti MA, Persegani C and Paggi A. (2000). Low doses of liquorice can induce hypertension encephalopathy. American Journal of Nephrology. 20:145-148.

[https://doi.org/10.1159/000013572]

-

Sailler L, Juchet H, Ollier S, Nicodème R and Arlet P. (1993). Generalized edema caused by licorice: A new syndrome. Apropos of 3 cases. La Revue de Medecine Interne. 14:984.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/S0248-8663(05)80102-X]

-

Santaella RM and Fraunfelder FW. (2007). Ocular adverse effects associated with systemic medications: Recognition and management. Drugs. 67:75-93.

[https://doi.org/10.2165/00003495-200767010-00006]

-

Tacconi P, Paribello A, Cannas A and Marrosu M. (2009). Carpal tunnel syndrome triggered by excessive licorice consumption. Journal of the Peripheral Nervous System. 14:64-65.

[https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1529-8027.2009.00207.x]

-

Thomas Q, Frank R, Sidney S and Lüscher TF. (2001). Aldosterone receptor antagonism normalizes vascular function in liquorice-induced hypertension. Hypertension. 37:801-805.

[https://doi.org/10.1161/01.HYP.37.2.801]

-

Tsukamoto S, Aburatani M, Yoshida T, Yamashita Y, El-Beih A and Ohta T. (2005). CYP3A4 inhibitors isolated from licorice. Biological and Pharmaceutical Bulletin. 28:2000-2002.

[https://doi.org/10.1248/bpb.28.2000]

- Tuvshintogtokh I, Mandakh BM, Yasufuku N, Omine K, Marui A, Bat-Enerel B and Yeruult Y. (2013). Some results of ecological research of uralian licorice(Glycyrrhiza uralensis Fisch.) in Mongolia. Proceedings of EAEP 2013. 1:98-103.

-

Van der Zwan A. (1993). Hypertension encephalopathy after liquorice ingestion. Clinical Neurology and Neurosurgery. 95:35-37.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/0303-8467(93)90089-Y]

- Yamamoto Y and Tani T. (2002). Growth and glycyrrhizin contents in Glycyrrhiza uralensis roots cultivated for four years in Eastern Nei-Meng-gu of China. Journal of Traditional Medicine. 19:87-92.

-

Yamamoto Y, Majima T, Saiki I and Tani T. (2003). Pharmaceutical evaluation of Glycyrrhiza uralensis roots cultivated in Eastern Nei-Meng-Gu of China. Biological and Pharmaceutical Bulletin. 26:1144-1149.

[https://doi.org/10.1248/bpb.26.1144]