Lipopolysaccharide 처리에 의해 유발된 RAW 264.7 세포 및 λ-carrageenan 처리에 의해 유발된 부종 마우스 모델에서 호장근 열수 추출물의 항염증 효과

#Jong Hui Kim and Min Hong are contributed equally to this paper.

This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/) which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Abstract

Polygonum cuspidatum, a plant commonly used in traditional medicine, possesses various pharmacological properties, including anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties. However, understanding whether P. cuspidatum exerts anti-inflammatory effects and elucidating its underlying mechanisms remain limited. In this study, we evaluated the anti-inflammatory effects of P. cuspidatum hot water extract (PWE) using lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced RAW 264.7 cells and a λ-carrageenan (λCAR)-induced paw edema C57BL/6 mouse model.

To evaluate the anti-inflammatory efficacy of PWE, a nitric oxide (NO) assay, quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction, and western blotting were performed. At PWE 400 ㎍/㎖, NO generation was reduced by 51.53 ± 1.94%, compared to that using LPS-stimulated RAW 264.7 cells. PWE also inhibited the interleukin (IL)-1β, IL-6, and tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α in a dose-dependent manner at the protein and mRNA levels. Additionally, an in vivo experiment was conducted using a λCAR-induced paw edema mouse model. Cytokine analysis in the λCAR-induced paw edema mouse model revealed that it strongly inhibited pro-inflammatory factors.

PWE has strong anti-inflammatory effects based on these results. We suggest that PWE can be used as a functional material for anti-inflammation and may be useful for preventing or treating inflammation.

Keywords:

Polygonum cuspidatum, Anti-inflammatory, λ-Carrageenan, Nitric Oxide, Paw Edema Animal Model, RAW 264.7 Cell서 언

염증은 체내에서 발생하는 다양한 자극에 대한 방어 기작으로, 외부 자극에 반응하여 면역 세포들이 활성화되고 염증 매개 물질을 분비하는 복잡한 생리적 과정이다 (Anderson and Mosser, 2002; Greten and Grivennikov, 2019).

염증 반응은 감염, 조직 손상, 화학적 자극 등에 의해 유발 될 수 있으며, 이러한 과정에서 대식세포와 호중구 같은 면역 세포들이 주요한 역할을 한다 (Siti et al., 2015). 대식세포는 인체의 여러 조직에 분포하며, 염증 발생 시 interleukin (IL)-1β, IL-6, tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α와 같은 전염증성 사이토카인들을 분비함으로써 염증 반응을 조절한다 (Kim et al., 2004). 특히, nitric oxide (NO)는 inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS)와 cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2)에 의해 생성되어 염증 반응에서 중요한 역할을 한다 (Sherwood and Toliver-Kinsky, 2004).

급성 염증은 손상 부위에서의 국소적 반응으로 혈관 확장, 혈액 성분의 유출, 그리고 호중구의 침윤을 특징으로 한다 (Chen et al., 2017). 이러한 급성 염증 반응은 일반적으로 신속하게 시작되고 짧은 기간 동안 지속되지만, 만성 염증으로 진전되는 경우 장기 손상과 같은 심각한 부작용을 초래할 수 있다 (Chen et al., 2017). 만성 염증은 류마티스 관절염, 염증성 장질환 및 크론병, 심혈관 질환 등 다양한 질병의 주요한 병리 기전으로 알려져 있으며, 염증 반응의 조절이 이러한 질환의 치료에 중요한 목표가 되고 있다 (Reddy et al., 2003).

호장근 (Polygonum cuspidatum)은 전통 한약재로 오랫동안 사용하고 있으며, 기침, 간염, 황달, 무월경, 백대하, 관절통, 고지혈증, 화상 및 멍, 뱀물림, 농양 치료에 흔히 처방되어 왔고 (Zhang et al., 2013), 항염증, 항산화, 항암, 항바이러스, 신경 및 심장 보호 효과 등이 약리 활성이 보고된 바 있다 (Cai et al., 2004; Zhang et al., 2013).

호장근에 포함된 주요 성분은 resveratrol, polysaccharides, rhodopsin, rhodopsin 유도체 및 emodin을 함유하고 있음을 확인하였고, (Ke et al., 2023), 호장근에 포함되어진 다당체 (Polygonum cuspidatum polysaccharide, PCP)가 높은 항종양, 항산화, 면역 증강 및 혈당 강하 효과를 나타낸다고 보고되고 있다 (Lai et al., 2024).

호장근의 주요 활성 성분 중 하나인 resveratrol은 특히 강력한 항염증 작용을 가지며, 염증 반응에서 중요한 역할을 하는 nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB) 경로를 억제하고, COX-2와 iNOS의 발현을 감소시킬 뿐 아니라 (Shakibaei et al., 2009; Kulkarni and Canto, 2015), 염증성 사이토카인의 생성을 억제하여 다양한 염증성 질환 모델에서 항염증 효과를 나타내는 것으로 보고되었다 (Aguirre et al., 2014). Resveratrol은 안구에서 포도막염 억제 및 류코트리엔 합성에 관여하는 COX를 차단하고 (Lançon et al., 2016), 노화방지 및 활성산 소종 생성, 사이토카인 신호전달을 억제함으로써 강한 항염 효과를 보인다 (Ghanim et al., 2010; Meng et al., 2021). Emodin 또한 강력한 항염 작용을 하는 성분으로써 (Stompor-Gorący, 2021), IκB를 활성화하여 RAW 264.7 대식세포에서 TNF-α, iNOS 및 IL-10에 대한 유전자 발현을 효과적으로 억제한다고 알려져 있다. (Tramposch et al., 1992).

본 연구는 호장근 열수 추출물 (PWE)의 항염증 효과를 체계적으로 분석하고, PWE의 염증 조절 메커니즘을 규명하는데 중점을 두었다. 특히, PWE의 NO 생산, iNOS 및 COX-2 단백질의 발현, 그리고 사이토카인의 조절을 통한 항염증 효과를 in vitro 및 in vivo 연구에서 확인하였으며 PWE에 함유된 유용성분에 대한 함량 분석을 실시하였다. 이를 통해 PWE가 가지는 항염증 효과의 메커니즘을 규명하고, 기능성 소재로서의 잠재력을 효과적으로 활용할 수 있는 기초 자료로 활용하고자 한다.

재료 및 방법

1. 시료 준비

본 실험에 사용된 호장근 (P. cuspidatum)은 뿌리 및 땅속줄기를 사용하였으며, 40℃에서 48 시간 동안 열풍 건조기 (KAPD-110D, DAEDONG dry machine, Seoul, Korea)를 사용하여 건조하였다.

건조 후, 분쇄기 (DA280-S, DAESUNG ARTLON, Paju, Korea)를 이용하여 80 mesh 크기로 분쇄하였고, 이후 온습도조절기 (DH.DeADDBG1K, DAIHAN Scientific Co., Ltd., Wonju, Korea)에서 23℃, 15%의 습도로 보관하였다.

이 중 100 g을 칭량한 후 1 ℓ의 증류수를 첨가하고 soxhlet extractor (MSEAM, MISUNG Co., Ltd., Yangju, Korea)를 이용하여 100℃에서 6 시간씩 환류 냉각 추출하였다. 추출 후 4,500 rpm에서 15 분간 원심분리 후 상층액을 Whatman No. 1 filter paper (Whatman™, Maidstone, England)를 이용하여 여과하고 동결건조 (PVTF20R, Ilshinbiobase, Dongduchun, Korea)하여 PWE를 제조하였다.

2. 세포배양

마우스 대식세포 RAW 264.7 cell을 이용하였다. RAW 264.7 세포는 American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Rockville, MD, USA)에서 구매하였으며, 이들 세포는 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc., Waltham, MA, USA)과 1% penicillin이 첨가된 Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc., Waltham, MA, USA) 배지에서 37℃, 5%의 CO2 조건 하에 배양하였다 (Heracell™ 150i CO2 Incubator, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc., Waltham, MA, USA)

3. 세포 생존율

배양된 RAW 264.7 cell을 1 × 104 cells/well로 96 well plate에 100 ㎕씩 분주하여 18 시간 동안 배양한 후 PWE를 농도별 시료 용액 (100 ㎍/㎖, 200 ㎍/㎖, 400 ㎍/㎖)을 각각 24 시간 동안 처리하였다.

시료 처리에 따른 세포 생존율은 Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8, #SE814 Dojindo Molecular Technologies, Rockville, MD, USA) 방법으로 확인하였으며 ELISA reader (SpectraMax M5, Molecular Devices, Sunnyuale, CA, USA)를 이용하여 450 ㎚에서 흡광도를 측정하였다.

4. Nitric oxide (NO) 생성량 측정

RAW 264.7 cell을 24 well 플레이트에 2 × 105 cells/well로 배양하여 24시간 동안 배양한 후, 1 ㎍/㎖ 농도의 lipopolysaccharide (LPS, Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO, USA)를 처리하였다.

LPS 처리 2 시간 후 PWE의 농도별 (100 ㎍/㎖, 200 ㎍/㎖, 400 ㎍/㎖) 시료를 각각 18 시간 동안 처리하였다. 상층액 내 NO의 농도는 NO detection kit (iNtRON, Seongnam, Korea)를 이용하여 확인하여 평가하였다.

5. RNA 추출 및 유전자 발현양상 측정

RAW 264.7 세포로부터 RNA를 RNA isolation kit (Qiagen Inc., Valencia, CA, USA)를 사용하여 분리하였으며, RNA의 순도는 NanoDrop (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc., Waltham, MA, USA)을 사용하여 확인하였다.

분리된 RNA는 reverse transcription master mix (Elpis-Biotech, Daejeon, Korea)를 사용하여 cDNA로 합성하였고, 상대 발현 수준은 LightCycler 480 Instrument II (05015243001, Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany)를 사용하여 확인하였다. Oligonucleotide primers는 Table 1과 같다.

6. 단백질 추출 및 발현양상 측정

단백질 수준에서 염증 인자 및 사이토카인에 대한 PWE의 효능을 확인하고자 RAW 264.7 cell을 2.5 × 105 cells/well의 농도로 6 well plate에 배양하였다. LPS (1 ㎍/㎖)를 처리하고 2 시간 동안 추가 배양하였으며, PWE의 농도별 시료 (100 ㎍/㎖, 200 ㎍/㎖, 400 ㎍/㎖)를 각각 24 시간 동안 처리하였다.

처리된 세포로부터 PRO-PREP™ (iNtRON Biotechnology, Seongnam, Korea)를 이용하여 단백질을 추출하였으며, 단백질 농도는 제조사의 프로토콜에 따라 Pierce™ BCA Protein Assay (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Rockford, IL, USA)를 사용하여 측정하였다.

단백질은 SDS-PAGE 및 항원-항체 반응을 사용한 웨스턴 블롯으로 분석되었으며, 1차 항체는 Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA, USA)에서 구매하였다. 항체 신호는 SuperSignal™ Western Blot Enhancer (Pierce, Rockford, IL, USA)를 사용하여 검출하였으며, LAS-4000 (Fujifilm, Tokyo, Japan)을 사용하여 확인하였다.

7. 동물실험

6 – 7 주령의 C57BL/6 계통 마우스 6 마리를 사용하여 표준화된 조건 (온도: 23 ± 2°C, 습도: 55 % ± 5 %, 빛: 12시간 주야간 주기)에서 자유롭게 음식과 물을 섭취할 수 있도록 사육하였다.

급성 염증은 우측 후족에 0.5%-carrageenan (λCAR), (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO, USA) 50 ㎕를 주입하여 유도하였고, 대조군에는 멸균 생리식염수를 주입하였다. 경구투여 물질은 모두 0.5% Carboxy methyl cellulose (CMC)에 혼합하여 경구로 투여되었다. PWE는 경구 투여 존데 (feeding needle)를 사용하여 경구 투여하였으며, 0.5%-λCAR 주입 3 일 전과 주입 당일에 투여하였다.

0.5%-λCAR 주입 4 시간 후 발의 부종을 캘리퍼스 (CD-30c, Mitutoyo Corporation, Kawasaki, Japan)를 사용하여 측정하였고, 후족을 채취하여 액체 질소로 동결한 후 절구와 막자사발을 사용하여 분쇄하였다. PRO-PREP™ (iNtRON Biotechnology, Seongnam, Korea)을 사용하여 분쇄된 조직 시료로부터 단백질을 추출하였으며, 단백질 농도는 제조사의 프로토콜에 따라 Pierce™ BCA Protein Assay (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Rockford, IL, USA)를 사용하여 측정하였다.

iNOS, COX-2, IL-1β, IL-6 및 TNF-α의 수준은 ELISA 키트를 사용한 효소 면역 분석을 통해 분석하였다. (iNOS: MBS261100, BIOsource, San Diego, CA, USA; COX-2: MBS269104, BIOsource, San Diego, CA, USA; IL-1β: SMLB00C, R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA; IL-6: ab100713, Abcam, Cambridge, Cambs, UK; TNF-α: BMS607-3, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). 모든 실험은 모든 기관관리 지침에 따라 진행되었다.

8. 성분 분석

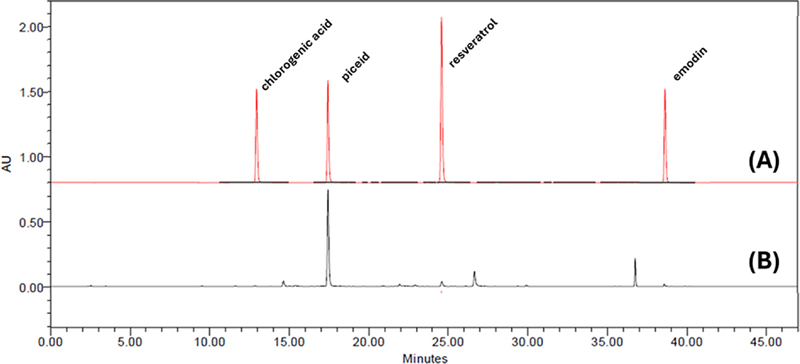

분석 시료를 2.0 ㎎/㎖의 농도로 70% ethanol에 용해하고 0.45 ㎛의 syringe filter를 이용하여 여과한 후 분석에 사용하였다.

분석을 위한 표준물질로는 piceid, resveratrol, emodin, chlorogenic acid (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA)를 70% ethanol에 각각 10, 100, 500, 1000 ㎍/㎖ 농도 희석하여 사용하였다.

Vial에 농도별로 희석된 표준물질과 시험용액을 100 ㎕ 씩 넣은 후 HPLC system (Waters Arc HPLC system, Frederick, MD, USA)를 이용하여 측정하였다. 분석에 사용된 컬럼은 역상 (reverse phase) 컬럼의 일종인 ProntoSIL 120-5 C18 ACE EPS column (4.6 ㎜ × 250 ㎜, 3.0 ㎛, Bischoff Chromatography, Leonberg, Germany)를 30℃에서 사용하였고, UV detector 206 ㎚에서 검출되었다.

이동상은 water (solvent A)와 acetonitrile (solvent B)를 사용하였으며, solvent B를 기준으로 초기부터 4 분까지는 solvent B를 10% 수준으로 유지하였으며 4 분부터 30 분까지 solvent B를 10%에서 40%까지 증가시켰고 30 분부터 36 분까지 solvent B를 40%에서 90%까지 증가시켰으며 36 분부터 47 분까지 다시 초기 상태인 solvent B를 10%로 감소시키는 gradient system을 적용하였고, 이동상의 속도는 분 당 1 ㎖로 조정하여 흘려주었으며, 이때 injection volume은 10.0 ㎕이었다.

9. 통계처리

실험 결과는 3 번 이상 반복 독립 실험으로 진행되었으며 모든 결과는 평균 ± 표준편차 (means ± SD)로 표시하였다.

실험 결과는 GraphPad Prism (GraphPad Software 8.0.1, GraphPad, San Diego, CA, USA)로 도식화하였으며 각 실험 결과에 대한 통계 분석은 one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA)를 실시한 후 Tukey HSD 다중분석법을 사용하여 각 처리구 간의 유의적 차이를 5%, 1%, 0.1% 수준에서 검증하였다 (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001).

결 과

1. PWE의 RAW 264.7 세포 생존율에 미치는 효과

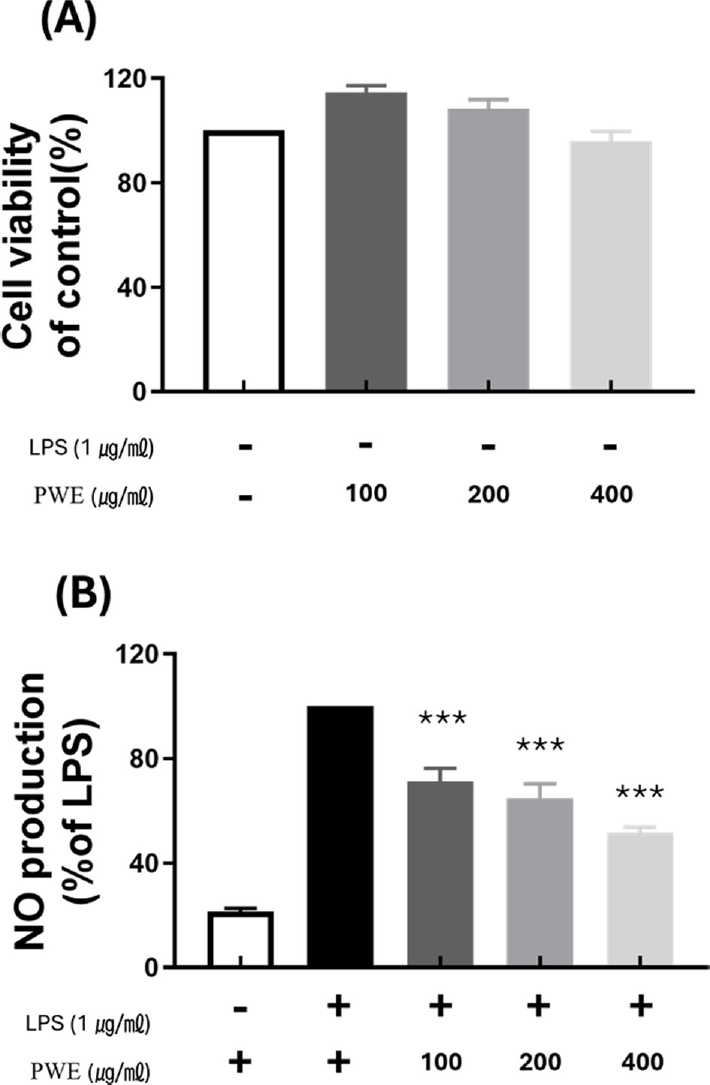

PWE의 세포 독성을 확인하기 위하여 RAW 264.7 세포를 대상으로 하여 PWE 농도별 (100 ㎍/㎖, 200 ㎍/㎖, 400 ㎍/㎖) 세포 생존률을 측성하였다.

그 결과 아무것도 처리하지 않은 control 군과 비교하여 PWE를 100 ㎍/㎖, 200 ㎍/㎖ 및 400 ㎍/㎖의 농도 수준으로 처리한 후 세포 생존률은 각각 114.68 ± 2.07%, 108.25 ± 2.92%, 96.08 ± 2.95%로 확인되었다. PWE의 최대 농도 400 ㎍/㎖ 이하에서 RAW 264.7 세포에 대하여 독성이 없음을 확인하였다 (Fig. 1A).

Effect of P. cuspidatum hot water extract (PWE) on LPS-stimulated nitric oxide (NO) generation and cell viability in RAW 264.7 cell.(A) results for cell viability at various concentration of PWE compared to control. (B) results of inhibition of NO production rate at various concentration of PWE compared to LPS-only treatment group. Data represent the means ± SD in triplicate. P-value were calculated based on LPS-only data by ANOVA and Tukey’s t-test (***p < 0.001).

2. PWE의 LPS로 유도된 NO 생성에 미치는 효과

LPS가 처리된 RAW 264.7 세포에 PWE를 100 ㎍/㎖, 200 ㎍/㎖ 및 400 ㎍/㎖의 농도 수준으로 처리한 후 NO의 생성량을 측정하였다.

LPS를 단독 처리한 군과 비교하여 (100%) 아무것도 처리되지 않은 대조군의 NO 생성 비율은 LPS를 처리구의 20.87 ± 0.77% 수준으로 확인되었으며 LPS 처리에 따라 NO 생성량이 크게 증가하였다.

반면 LPS를 처리하고 PWE를 100 ㎍/㎖, 200 ㎍/㎖ 및 400 ㎍/㎖의 농도 수준으로 처리한 경우 NO 생성 비율은 각각 농도에 따라 LPS 단독 처리군 (100%) 대비 71.20 ± 4.39%, 64.83 ± 4.80%, 51.53 ± 1.94%로 감소하는 것으로 나타났다 (Fig. 1B). 이에 따라 PWE는 농도 의존적으로 NO 생성 비율을 감소시킬 수 있는 것으로 확인되었다.

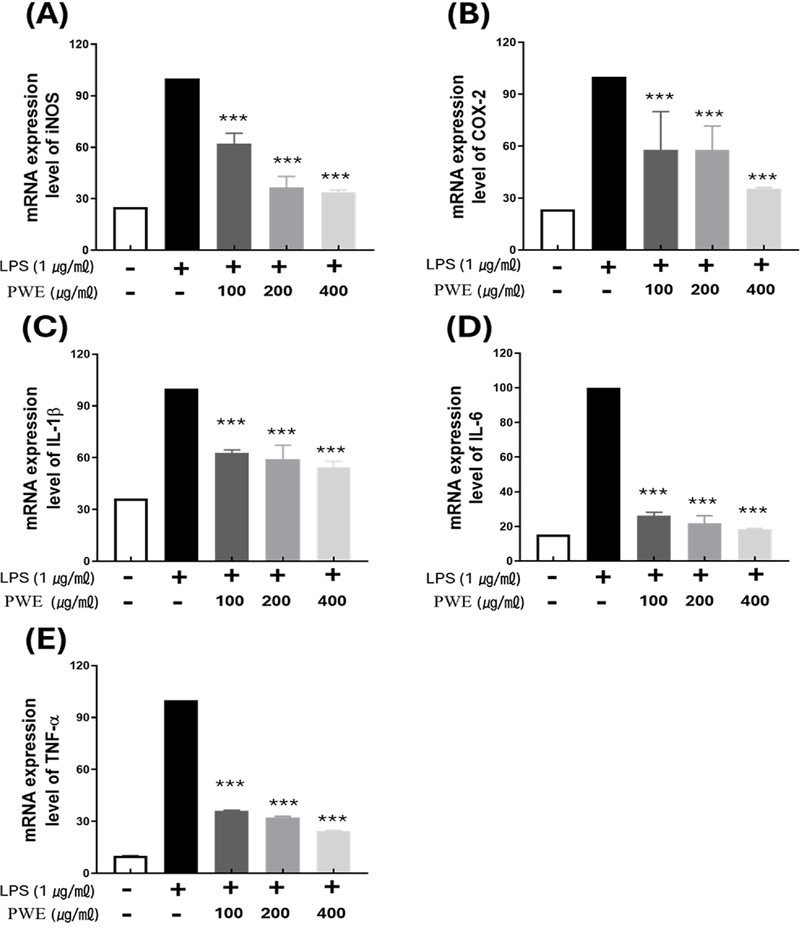

3. PWE이 iNOS, COX-2 및 염증성 사이토카인의 mRNA 발현에 미치는 효과

PWE의 염증성 사이토카인의 생성과 염증 발현과 관련된 유전자의 전사에 미치는 영향을 확인하기 위하여 LPS를 처리하여 면역반응이 유도된 RAW 264.7 세포를 대상으로 PWE를 처리에 따른 세포에서의 NO 생성과 연관된 iNOS, COX-2 및 염증성 사이토카인 (TNF-α, IL-1β 및 IL-6)의 유전자의 전사에 미치는 효과를 RT-PCR을 통하여 확인하였다.

LPS가 처리되지 않은 control에서의 iNOS, COX-2, 염증성 사이토카인 IL-1β, IL-6 및 TNF-α mRNA 발현은 거의 확인 되지 않은 반면, LPS를 단독 처리한 군에서는 각 유전자의 발현이 급격히 증가하는 것이 확인되었다.

LPS를 처리하고 PWE를 100 ㎍/㎖, 200 ㎍/㎖ 및 400 ㎍/㎖의 농도 수준으로 처리한 경우 LPS를 단독 처리한 군의 mRNA 발현 수준을 100%로 하여 비교한 결과 iNOS mRNA 발현 수준은 각각의 농도에 따라 62.09 ± 4.30%, 36.61 ± 4.54% 그리고 33.79 ± 0.82%로 나타나 mRNA 발현 수준이 감소함을 확인할 수 있었다 (Fig. 2A).

Inhibitory effect of inflammation-inducing mRNA of PWE.All samples except control were treated with 1 ㎍/㎖ of LPS. Compared to (A) iNOS, (B) COX-2, (C) IL-1β (D) IL-6, (E) TNF-α mRNA expression levels based on LPS-only treatment. Data represent the means ± SD in triplicate. P-value were calculated based on LPS-only data by ANOVA and Tukey’s t-test (***p < 0.001).

COX-2의 경우에서도 LPS 처리에 의해 증가된 mRNA 발현 수준은 PWE를 각 농도별로 처리함에 따라 57.82 ± 15.63% (100 ㎍/㎖), 57.78 ± 9.18% (200 ㎍/㎖), 35.49 ± 0.49% (400 ㎍/㎖)로 감소되어지는 경향을 보였다 (Fig. 2B).

사이토카인 중 하나인 IL-1β는 LPS를 단독 처리한 경우와 비교하여 PWE를 100 ㎍/㎖, 200 ㎍/㎖ 및 400 ㎍/㎖의 농도 수준으로 처리함 따라 62.67 ± 1.30% 59.15 ± 5.72%, 54.41± 2.45%로 발현양이 각각 감소하였다 (Fig. 2C).

IL6 경우에서도 PWE의 농도에 따라 순서대로 26.18 ± 13.6%, 21.76 ± 3.07%, 18.34 ± 0.34%까지 발현 수준이 감소하고, TNF-α 또한 농도에 따라 각각 36.17 ± 0.17%, 32.38 ± 0.38%, 24.33 ± 0.32%로 mRNA 발현 수준이 감소하였다 (Fig. 2D, 2E).

이러한 결과를 통해 PWE의 처리는 염증 발현 관련 유전자의 mRNA 발현을 농도 의존적으로 저해할 수 있다는 것을 검증하였으며 호장근 추출물이 염증 발현 억제에 효과적으로 사용될 수 있음을 확인하였다.

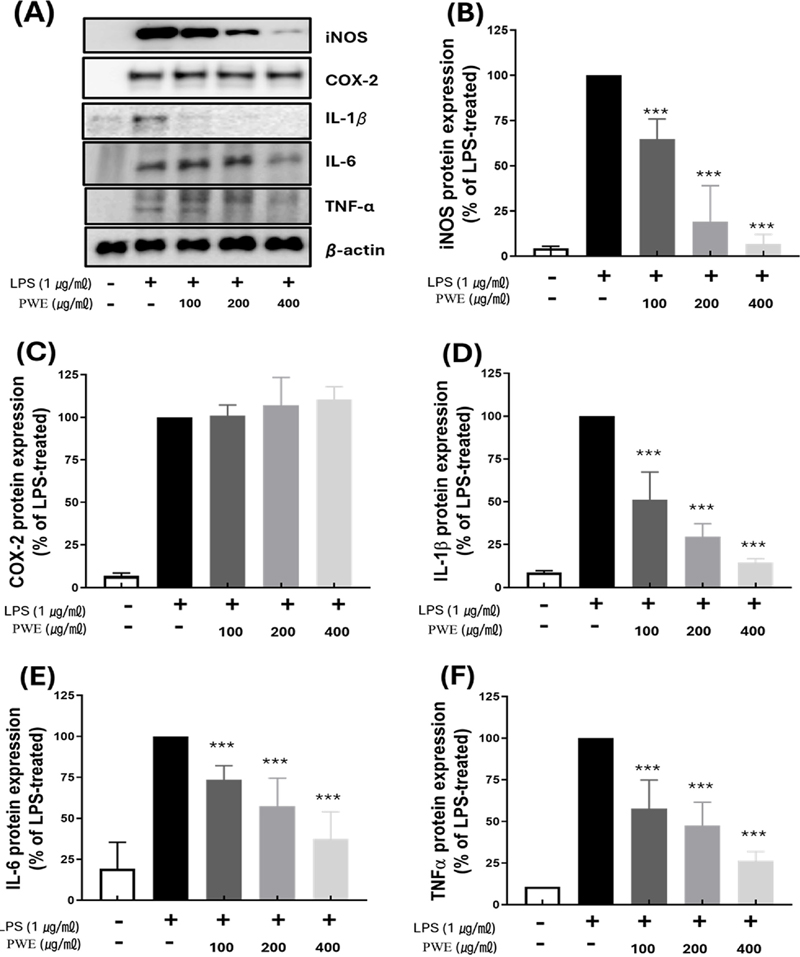

4. PWE가 iNOS, COX-2 및 염증성 사이토카인의 단백질 발현에 미치는 효과

전사 단계에서 확인된 PWE의 항염증 효능을 Western blot을 이용하여 단백질 수준에서 같은 저해 활성을 나타내는지 확인하였다 (Fig. 3A).

Inhibitory effect of inflammation-inducing protein of PWE.All samples except control were treated with 1 ㎍/㎖ of LPS. (A) Western blot detection bands of each protein. Compared to (B) iNOS, (C) COX-2, (D) IL-1β (E) IL-6 (F) TNF-α protein expression levels based on LPS-only treatment. P-value were calculated based on LPS-only data by ANOVA and Tukey’s t-test (***p < 0.001).

LPS가 처리되지 않은 대조군에서의 iNOS, COX-2 및 염증성 사이토카인 단백질 발현이 거의 이루어지지 않는 수준인 반면, LPS를 단독 처리한 군의 경우 모두 그 발현이 크게 증가됨을 확인할 수 있었다.

LPS 단독 처리구 (100%)에 대비하여 PWE를 100 ㎍/㎖, 200 ㎍/㎖ 및 400 ㎍/㎖의 농도로 처리한 경우 각각 농도에 따라 iNOS의 단백질 발현은 64.68 ± 9.64%, 19.08 ± 9.64%, 6.88 ± 4.45% 로 크게 감소하였다 (Fig. 3B). 사이토카인 IL-1β, IL-6 및 TNF-α 단백질의 경우 PWE 400 ㎍/㎖에서 LPS 단독 처리구 (100%) 대비, 14.39 ± 1.77%, 26.38 ± 4.44%, 37.37 ± 14.4% 으로 단백질의 발현 비율을 감소함을 알 수 있었다 (Fig. 3D, 3E, and 3F).

반면 COX-2 단백질 발현에 있어 LPS 단독 처리구 (100%) 대비, PWE를 100 ㎍/㎖, 200 ㎍/㎖ 및 400 ㎍/㎖의 농도로 처리한 경우 COX-2의 단백질 발현 비율은 각각 101.06 ± 6.29%, 107.21 ± 15.96%, 110.65 ± 7.27% 순으로 PWE의 농도에 따른 유의미한 변화가 확인되지 않았다 (Fig. 3C)

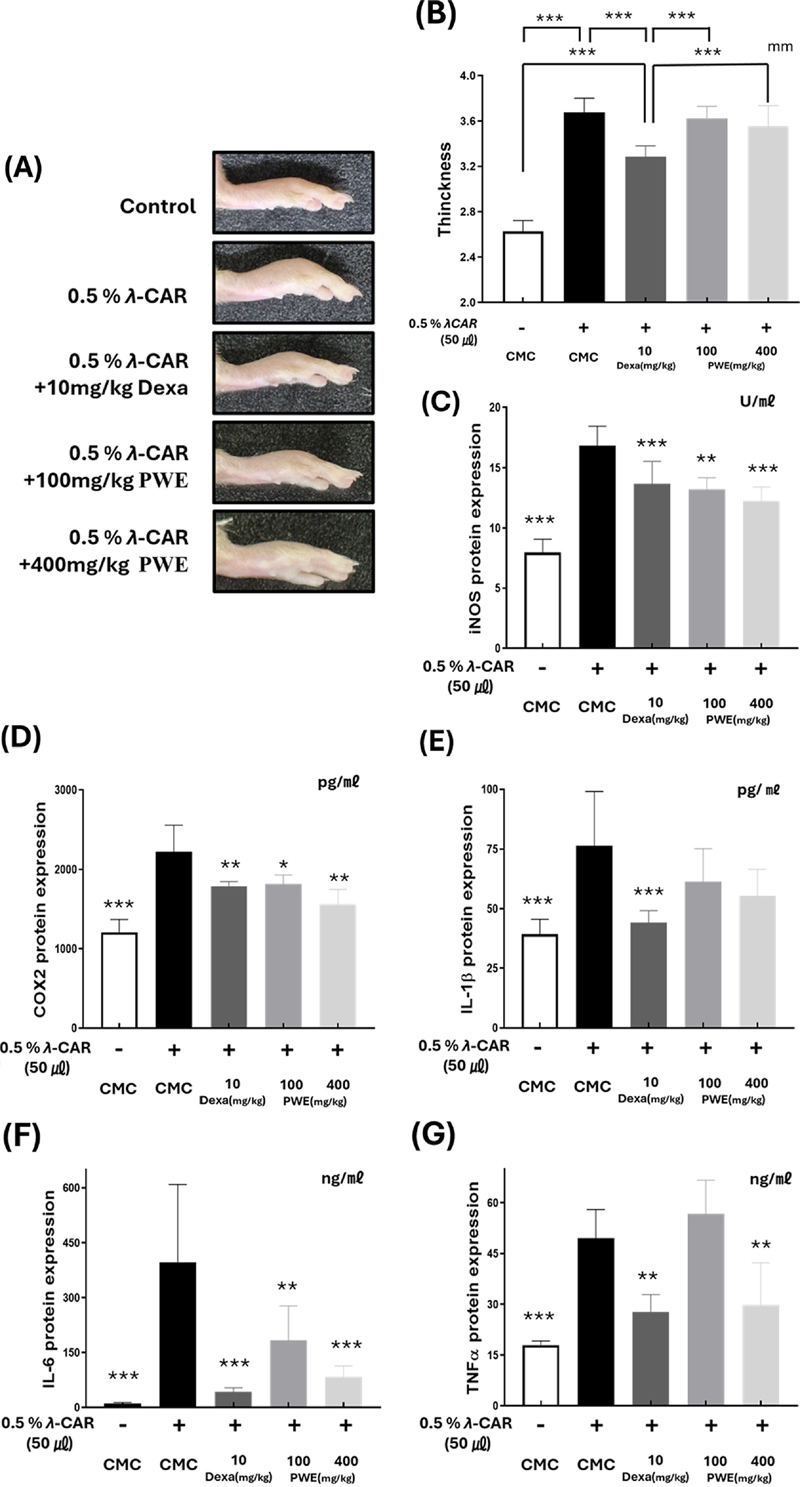

5. PWE가 ?-carrageenan으로 유발된 마우스의 급성 염증 반응에 미치는 효과

PWE의 in vivo 항염증 효과는 0.5% λ-carrageenan (λCAR)으로 유도된 급성 염증 모델을 이용하여 확인되었다. 고농도 (400 ㎎/㎏)와 저농도 (100 ㎎/㎏)의 PWE는 모두 0.5% λCAR 단독 처리군과 비교했을 때 부종 크기에 변화를 보이지 않았다. 반면, 양성 대조군인 dexamethasone (Dexa) 10 ㎎/㎏을 처리한 그룹은 λCAR를 0.5%만 주입한 그룹과 비교하여, 0.5% λCAR 주입 후 4 시간 경과 시점에서 유의미한 차이를 보였다 (Fig. 4A and 4B).

Effects of PWE on λCAR-induced edema in mice.Paw edema and inflammatory factor production in mice induced by λCAR. 0.5% Carboxy methyl cellulose (CMC) was administered orally as a normal control. As a positive control, Dexamethasone (Dexa), a synthetic adrenal cortex hormone with anti-inflammatory effects, was treated. (A) Paw edema was measured using calipers 4 h after λCAR administration and compared with that in the normal group. The production of inflammatory factors, including (C) iNOS, (D) COX-2, (E) IL-1β, (F) IL-6, and (G) TNF-α, was assessed using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). P-value was calculated based on LPS-only data using ANOVA and Tukey’s post-hoc test (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001).

λCAR 0.5%로 처리된 마우스의 발 조직에서 단백질을 추출한 후, ELISA를 사용하여 염증 인자를 분석하였다. iNOS는 PWE의 농도에 따라 각각 0 ㎎/㎏에서 16.84 ± 1.47 U/㎖, 100 ㎎/㎏에서 13.22 ± 0.88 U/㎖, 400 ㎎/㎏에서 12.22 ± 1.08 U/㎖로 억제되었다 (Fig. 4C).

λCAR 0.5%만 주입된 그룹에서 COX-2는 2,222.36 ± 305.52 pg/㎖로 증가하였고, PWE를 100 ㎎/㎏ 및 400 ㎎/㎏ 경구 투여한 그룹에서는 각각 1,813.79 ± 106.46 pg/㎖, 1,559.69 ± 170.95 pg/㎖로 COX-2가 억제되었다 (Fig. 4D).

λCAR 0.5% 주입으로 과발현된 IL-6는 100 ㎎/㎏ 및 400 ㎎/㎏의 PWE 경구 투여를 통해 각각 396.50 ± 190.08 ng/㎖에서 182.93 ± 85.97 ng/㎖, 83.46 ± 27.23 ng/㎖로 억제되었다 (Fig. 4F).

또한 TNF-α는 낮은 농도 (100 ㎎/㎏)의 PWE의 경우 유의미한 감소가 관찰되지 않았으나, 고농도 PWE (400 ㎎/㎏)를 처리한 경우 λCAR 0.5% 주입으로 증가한 TNF-α의 함량이 (49.54 ± 7.68 ng/㎖) PWE를 고농도로 처리함에 따라 29.81 ± 11.34 ng/㎖의 수준으로 감소하였다 (Fig. 4G).

반면에 IL-1β의 경우 λCAR 0.5% 주입으로 높은 수준으로 증가된 함량 (76.34 ± 20.67 pg/㎖)이 저농도 및 고농도의 PWE 처리에도 유의미한 변화를 나타내지 않았다 (Fig. 4E).

PWE는 부종 조직 크기를 유의미하게 감소시키지 못했으나, 마우스 발 부종 조직에서 iNOS, COX-2, IL-6 및 TNF-α의 염증 인자의 생성을 유의미하게 감소시켰으므로 PWE는 단백질 수준에서 급성 염증을 유발한 마우스에서 염증 반응을 억제할 수 있음을 확인할 수 있었다.

6. PWE의 지표물질 함량

본 연구에서는 PWE에서 효능 성분을 확인하기 위하여 HPLC system으로 분석하였다. 추출한 piceid, resveratrol, emodin, chlorogenic acid의 유효성분이 확인되었으며 함량을 확인하고 각 성분의 검출 시간과 함량을 비교하였다.

4 가지 성분이 모두 45 분 이내에 용리되었으며, 2 ㎎/㎖의 PWE 시료와 표준품으로 비교 · 분석한 결과, piceid가 60.60 ㎎/g으로 가장 높은 함량을 보였다 (Fig. 5). Resveratrol과 emodin은 각각 2.00 ㎎/g, 2.02 ㎎/g로 비슷한 수준으로 검출되었으며, 마지막으로 chlorogenic acid는 0.511 ㎎/g으로 가장 적은 함량을 보였다 (Fig. 5).

고 찰

호장근 (P. cuspidatum)은 전통적으로 사용되는 약초로 67개 이상의 화합물이 분리되어 확인되었다 (Peng et al., 2013). 호장근에는 안트라퀴논 계열의 성분 (rhein, emodin, physcion), 플라보노이드 계열의 성분 (quercetin, apigenin) 및 쿠마린, 나프탈렌 및 글리코사이드 등의 유효성분이 포함되어있다 (Peng et al., 2013).

본 연구에서 사용된 PWE에서도 piceid, resveratrol, emodin, chlorogenic acid의 성분을 확인하였다 (Fig. 5). Piceid는 resveratrol 전구체로 resveratrol은 호장근에 가장 많이 함유되어 있는 물질 중 하나이다 (Ghanim et al., 2010; Moshtaghion et al, 2024). 본 연구에서는 piceid의 함량이 추출물 내에서 60.60 ㎎/g으로 가장 높은 수준임을 확인하였으며, 이는 추출방법이 piceid와 같은 glycoside를 효과적으로 보존했음을 의미합니다 . Piceid는 체내에서 효소에 의해 resveratrol로 전환 될 수 있으며, 그 과정에서 생리적 효과를 발휘합니다.

일반적으로 resveratrol은 호장근에서 95% 에탄올로 환류하여 추출한 다음 일부 유기 용매를 사용하여 액-액 분배 방식 (liquid-liquid extraction)으로 추출하고 있으나 (Mantegna et al., 2012; Sun et al., 2021), 이 추출 과정은 복잡하고 시간이 많이 걸리며 상당한 양의 용매가 사용되기 때문에 실용화 장애가 되고 있다. 또한, 호장근에 포함되어진 resveratrol은 주로 piceid (resveratrol-3-O-β-mono-D-glucoside))라고 불리는 glycosides 형태로 존재하며, 그 함량은 aglycone 형태인 resveratrol보다 10 배 이상 높다고 알려져 있는데 (Chong et al., 2012), 최근 연구에 따르면 호장근을 대상으로 한 물 추출물을 제조하고 이 추출물에 산 및 알칼리 가수분해 (Lin et al., 2016), glucose oxidase와 같은 효소를 사용하여 (Chen et al., 2016) glycosides 형태인 piceid를 aglycone 형태인 resveratrol로 생물전환하여 수율을 향상시킬 수 있다고 보고한 바 있다.

호장근으로부터 유기용매를 사용하여 여러 공정을 거쳐 직접적으로 resveratrol을 생산하는 것보다 호장근을 대상으로 물 추출물을 제조하고 생물전환기술을 적용함으로써 수율을 효율적으로 향상시킬 수 있을 뿐만 아니라 용매 사용 및 오염을 방지할 수 있어 산업적 생산에 좋은 이점을 나타낼 수 있다. 이러한 이유로 호장근에 대한 물 추출물의 제조와 이에 대한 약리 활성의 평가, 유효성분에 대한 함량 검정이 필요하며 이러한 연구는 호장근으로부터 glycoside를 추출하고 가수분해과정의 생물전환공정의 적용을 통해 resveratrol의 함량을 증가시킬 수 있는 공정개발에 기초 자료로 활용될 수 있을 것으로 생각된다.

Macrophages는 인체 전반에 분포하며 선천 면역 및 염증의 중요 역할을 하며 (Gordon and Martinez-Pomares , 2017) 다양한 염증 과정에 관여하는 IL-1, IL-6, 및 TNF-α와 같은 염증 촉진 사이토카인을 생성하는 것이 특징이다 (Gordon and Martinez-Pomares , 2017).

염증은 NF-kB 신호 전달 체계나 AMP 활성화 단백질 키나아제 (AMPK) 경로, 포유류 라파마이신 표적 (mTOP) 신호 전달 경로 등의 체계적이고 복잡한 여러 경로가 상호적으로 관여되며 발생된다 (Liu et al., 2017; Andrabi et al., 2023). 이 과정중에서 발생된 iNOS는 NO의 생산을 증가시키고 COX-2는 prostaglandin E2 (PGE2)의 생성을 촉진한다 (Greenhough et al., 2009).

NO의 생성은 iNOS에 의해 생성되며 과한 iNOS의 증가 및 NO의 생성은 심혈관계 이상, 신경 염증을 통한 중추 신경계 문제, 폐혈성 쇼크등의 등 다양한 질병의 원인이 된다 (Sonar and Lal, 2019). COX-2가 과도하게 발현되면, 만성 염증성 질환을 촉진 시키며, COX-2는 PGE2를 통해 종양 성장 및 면역 회피를 유도하는 주요 경로로 작용하여 암을 악화시키는 주요 원인이다 (Jin et al., 2023). 강력한 염증성 사이토카인인 IL-1β, IL-6 및 TNF-α의 과한 증가는 만성 염증을 유발하여 염증은 류마티스 관절염, 염증성 장질환 등과 같은 자가면역질환을 발생시키며, 조직 손상 및 골 및 연골 조직의 손상을 유발을 촉진한다 (Timmen et al., 2014; Mohamed et al., 2024).

본 연구에서는 항염증 효능을 평가하기 위해 LPS로 유발되어진 RAW 264.7 세포를 이용하여 in vitro 및 in vivo에서 PWE의 영향을 확인하였다. PWE은 100 ㎍/㎖, 200 ㎍/㎖ 및 400 ㎍/㎖의 농도에서 세포 생존율이 80% 이상으로 유지되었으며 (Fig. 1A), LPS에 유도되어진 NO의 생성을 저해하는 효과를 나타냄을 확인하였다 (Fig. 1B). 또 400 ㎍/㎖의 농도에서 iNOS, COX-2, IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α의 mRNA의 발현을 33.79 ± 0.82%, 35.49 ± 0.49%, 54.41± 2.45%, 18.34 ± 0.34%, 24.33 ± 0.32% 수준까지 감소시켰다 (Fig. 2). 단백질의 발현에 있어서도 PWE 400 ㎍/㎖일 때 LPS 처리에 의해 증가된 iNOS, IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α의 단백질 발현을 6.88 ± 4.45%, 14.39 ± 1.77%, 26.38 ± 4.44%, 37.37 ± 14.4% 수준까지 저해했다 (Fig. 3A, 3B, 3D, 3E, 3F). 그러나 COX-2의 경우 단백질 수준에서 유의미한 변화가 관찰되지 않았다 (Fig. 3C). 이러한 결과는 mRNA 발현 양상과 단백질 발현양상의 사이에는 생물학적 기술적 요인으로 불일치가 발견되어진다는 이전의 연구결과 보고와 실제로 특정 mRNA와 해당 단백질의 차등 발현 간의 상관관계가 수많은 연구에서 발견되는 것으로 보고되어지고 있다 (Gry et al., 2009; Browne et al., 2020; Rachinger et al., 2021).

뮤코폴리사카라이드 추출물인 λ-carrageenan (λCAR)은 오랫동안 국소 염증 모델에서 자극제로 사용되어 국소 부종, 백혈구 침윤을 유도한다 (Myers et al., 2019). 우리는 0.5 %의 λCAR을 뒤의 뒷발에 주입하여 급성 염증 반응을 유도한 후, PWE를 경구 투여하여 항염 효능을 나타낼 수 있는지 확인하였다 (Fig. 4).

PWE는 주의 발의 부종의 유의적인 두께 변화를 나타내지는 못하였으나 iNOS, COX-2, IL-6 및 TNF-α 수치를 농도 의존적으로 감소시켰고 (Fig. 4), 특히 고농도 (400 ㎎/㎏)의 PWE를 처리한 경우 positive control로 사용된 dexametasone (Dexa)과 비교하여 iNOS, COX-2의 발현을 감소시키는 더 높은 활성을 나타내었다.

반면에 IL-1β의 경우 λCAR 주입으로 증가하였으나 PWE 투여에 따른 변화는 관찰되지 않아 유의미한 효과가 확인되지 않았다 (Fig. 4). IL-1β는 다른 사이토카인과 다르게 pro-IL-1β의 형태로 체내에 존재하다가 염증조절복합체 (inflammasome)에 의해 자극되어 IL-1β으로 분비된다 (Church et al., 2008; Hoffman and Wanderer, 2010).

Inflammasome은 선천 면역 체계 수용체이자 센서로 IL-1β는 Toll-like receptor (TLR)에 의한 자극을 통한 NF-κB 경로 및 NLRP3 inflammasome을 통해 독립적인 추가 신호전달 경로로 결합될 수 있는 특징을 가진다 (Church et al., 2008; Mitroulis et al., 2010). 이러한 특징에 기인하여 IL-1β의 활성화는 다른 염증성 인자들과 같은 방식으로 쉽게 억제되지 않을 가능성이 존재할 수 있다고 하겠다.

본 연구에서 실험된 항염증 지표에 대한 PWE의 저해 효과는 호장근의 항염증제 소재 활용을 위한 기초 연구로 제공되어 질 수 있을 것으로 생각된다. 또한 염증을 조절하는 사이토카인 각각의 추가적인 연구 및 호장근을 효과적으로 활용하기 위한 추출법 및 항염증 활성 본체에 대한 추가적인 연구의 필요성을 제시한다고 하겠다.

Acknowledgments

본 연구는 2024년도 교육부의 재원으로 한국연구재단의 지원을 받아 수행된 지자체-대학 협력기반 지역혁신 사업 (2022RIS-005)의 결과로 이에 감사드립니다.

References

-

Aguirre L, Fernández-Quintela A, Arias N and Portillo MP. (2014). Resveratrol: Anti-obesity mechanisms of action. Molecules. 19:18632-18655.

[https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules191118632]

-

Anderson CF and Mosser DM. (2002). Cutting edge: Biasing immune responses by directing antigen to macrophage Fc gamma receptors. Journal of Immunology. 168:3697-3701.

[https://doi.org/10.4049/jimmunol.168.8.3697]

-

Andrabi SM, Sharma NS, Karan A, Shahriar SS, Cordon B, Ma B and Xie J. (2023). Nitric oxide: Physiological functions, delivery, and biomedical applications. Advanced Science. 10:e2303259. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/advs, . 202303259 (cited by 2024 June 10).

[https://doi.org/10.1002/advs.202303259]

-

Browne DJ, Brady JL, Waardenberg AJ, Loiseau C and Doolan DL (2020). An analytically and diagnostically sensitive RNA extraction and RT-qPCR protocol for peripheral blood mononuclear cells. Frontiers in Immunology. 11:402. https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/immunology/articles/10.3389/fimmu.2020.00402/full, (cited by 2024 June 10).

[https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2020.00402]

-

Cai Y, Luo Q, Sun M, and Corke H. (2004). Antioxidant activity and phenolic compounds of 112 traditional Chinese medicinal plants associated with anticancer. Life Sciences. 74:2157-2184.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lfs.2003.09.047]

-

Chen H, Deng Q, Ji X, Zhou X, Kelly G and Zhang J. (2016). Glucose oxidase-assisted extraction of resveratrol from Japanese knotweed (Fallopia japonica). New Journal of Chemistry. 40:8131-8140.

[https://doi.org/10.1039/C6NJ01294A]

-

Chen L, Deng H, Cui H, Fang J, Zuo Z, Deng J, Li Y, Wang X, and Zhao L. (2017). Inflammatory responses and inflammation-associated diseases in organs. Oncotarget. 9:7204-7218.

[https://doi.org/10.18632/oncotarget.23208]

-

Chong Y, Yan A, Yang X, Cai Y and Chen J. (2012). An optimum fermentation model established by genetic algorithm for biotransformation from crude polydatin to resveratrol. Applied Biochemistry and Biotechnology. 166:446-457.

[https://doi.org/10.1007/s12010-011-9440-7]

-

Church LD, Cook GP and McDermott MF (2008). Primer: Inflammasomes and interleukin 1beta in inflammatory disorders. Nature Reviews Rheumatology. 4:34-42.

[https://doi.org/10.1038/ncprheum0681]

-

Ghanim H, Sia CL, Abuaysheh S, Korzeniewski K, Patnaik P, Marumganti A, Chaudhuri A and Dandona P. (2010). An anti-inflammatory and reactive oxygen species suppressive effects of an extract of Polygonum cuspidatum containing resveratrol. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 95:E1-E8. https://academic.oup.com/jcem/article/95/9/E1/2835126, (cited by 2024 June 10).

[https://doi.org/10.1210/jc.2010-0482]

-

Gordon S, Martinez-Pomares L. (2017) Physiological roles of macrophages. Pflugers Archive. 469:365-374

[https://doi.org/10.1007/s00424-017-1945-7]

-

Greenhough A, Smartt HJM, Moore AE, Roberts HR, Williams AC, Paraskeva C and Kaidi A. (2009). The COX-2/PGE2 pathway: Key roles in the hallmarks of cancer and adaptation to the tumour microenvironment. Carcinogenesis. 30:377-386.

[https://doi.org/10.1093/carcin/bgp014]

-

Greten FR and Grivennikov SI. (2019). Inflammation and cancer: Triggers, mechanisms, and consequences. Immunity. 51:27-41.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.immuni.2019.06.025]

-

Gry M, Rimini R, Strömberg S, Asplund A, Pontén F, Uhlén M and Nilsson P. (2009). Correlations between RNA and protein expression profiles in 23 human cell lines. BMC Genomics. 10:365. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1186/1471-2164-10-365, (cited by 2024 June 10).

[https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2164-10-365]

-

Hoffman HM and Wanderer AA. (2010). Inflammasome and IL-1beta-mediated disorders. Current Allergy and Asthma Reports. 10:229-235.

[https://doi.org/10.1007/s11882-010-0109-z]

-

Jin K, Qian C, Lin J and Liu B. (2023). Cyclooxygenase-2-Prostaglandin E2 pathway: A key player in tumor-associated immune cells. Frontiers in Oncology. 13:1099811. https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/oncology/articles/10.3389/fonc.2023.1099811/full, (cited by 2024 June 10).

[https://doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2023.1099811]

-

Ke J, Li MT, Xu S, Ma J, Liu MY and Han Y. (2023). Advances for pharmacological activities of Polygonum cuspidatum-A review. Pharmaceutical Biology. 61:177-188.

[https://doi.org/10.1080/13880209.2022.2158349]

-

Kim HP, Son KH, Chang HW and Kang SS. (2004). Anti-inflammatory plant flavonoids and cellular action mechanisms. Journal of Pharmacological Sciences. 96:229-245.

[https://doi.org/10.1254/jphs.CRJ04003X]

-

Kulkarni SS and Cantó C. (2015). The molecular targets of resveratrol. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 1852:1114-1123.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbadis.2014.10.005]

-

Lai JY, Fan XL, Zhang HB, Wang SC, Wang H, Ma X. and Zhang ZQ. (2024). Polygonum cuspidatum polysaccharide: A review of its extraction and purification, structure analysis, and biological activity. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 331:118079. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0378874124003787, (cited by 2024 June 10).

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jep.2024.118079]

-

Lançon A, Frazzi R and Latruffe N. (2016). Anti-oxidant, anti-inflammatory and anti-angiogenic properties of resveratrol in ocular diseases. Molecules. 21:304. https://www.mdpi.com/1420-3049/21/3/304, (cited by 2024 June 10).

[https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules21030304]

-

Lin JA, Kuo CH, Chen BY, Li Y, Liu YC, Chen JH and Shieh CJ. (2016). A novel enzyme-assisted ultrasonic approach for highly efficient extraction of resveratrol from Polygonum cuspidatum. Ultrasonics Sonochemistry. 32:258-264.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ultsonch.2016.03.018]

-

Liu T, Zhang L, Joo D and Sun SC. (2017). NF-κB signaling in inflammation. Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy. 2:17023. https://www.nature.com/articles/sigtrans201723, (cited by 2024 June 10).

[https://doi.org/10.1038/sigtrans.2017.23]

-

Mantegna S, Binello A, Boffa L., Giorgis M, Cena C and Cravotto G. (2012). A one-pot ultrasound-assisted water extraction/cyclodextrin encapsulation of resveratrol from Polygonum cuspidatum. Food Chemistry. 130:746-750.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2011.07.038]

-

Meng T, Xiao D, Muhammed A, Deng J, Chen L and He J. (2021). Anti-inflammatory action and mechanisms of resveratrol. Molecules. 26:229. https://www.mdpi.com/1420-3049/26/1/229, (cited by 2024 June 10).

[https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules26010229]

-

Mitroulis I, Skendros P and Ritis K. (2010). Targeting IL-1β in disease; The expanding role of NLRP3 inflammasome. European Journal of Internal Medicine. 21:157-163.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejim.2010.03.005]

-

Mohamed AAH, Ahmed AT, Al Abdulmonem W, Bokov DO, Shafie A, Al-Hetty HRAK, Hsu CY, Alissa M, Nazir S, Jamali MC and Mudhafar M. (2024). Interleukin-6 serves as a critical factor in various cancer progression and therapy. Medical Oncology. 41:182. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s12032-024-02422-5, (cited by 2024 June 10).

[https://doi.org/10.1007/s12032-024-02422-5]

-

Moshtaghion SM, Caballano-Infantes E, Plaza Reyes Á, Valdés-Sánchez L, Fernández PG, de la Cerda B, Riga MS, Álvarez-Dolado M, Peñalver P, Morales JC and Díaz-Corrales FJ. (2024). Piceid octanoate protects retinal cells against oxidative damage by regulating the Sirtuin 1/poly-ADP-ribose polymerase 1 axis in vitro and in rd10 mice. Antioxidants. 13:201. https://www.mdpi.com/2076-3921/13/2/201, (cited by 2024 June 10).

[https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox13020201]

-

Myers MJ, Deaver CM and Lewandowski AJ. (2019). Molecular mechanism of action responsible for carrageenan-induced inflammatory response. Molecular Immunology. 109:38-42.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molimm.2019.02.020]

-

Peng W, Qin R, Li X and Zhou H. (2013). Botany, phytochemistry, pharmacology, and potential application of Polygonum cuspidatum Sieb.et Zucc.: A review. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 148:729-745.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jep.2013.05.007]

-

Rachinger N, Fischer S, Böhme I, Linck-Paulus L, Kuphal S, Kappelmann-Fenzl M and Bosserhoff AK. (2021). Loss of gene information: Discrepancies between RNA sequencing, cDNA microarray, and qRT-PCR. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 22:9349. https://www.mdpi.com/1422-0067/22/17/9349, (cited by 2024 June 10).

[https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms22179349]

-

Reddy L, Odhav B and Bhoola KD. (2003). Natural products for cancer prevention: A global perspective. Pharmacology and Therapeutics. 99:1-13. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0163725803000421, (cited by 2024 June 10).

[https://doi.org/10.1016/S0163-7258(03)00042-1]

-

Shakibaei M, Harikumar KB and Aggarwal BB. (2009). Resveratrol addiction: To die or not to die. Molecular Nutrition and Food Research. 53:115-128.

[https://doi.org/10.1002/mnfr.200800148]

-

Sherwood ER and Toliver-Kinsky T. (2004). Mechanisms of the inflammatory response. Best Practice and Research Clinical Anaesthesiology. 18:385-405.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bpa.2003.12.002]

-

Siti HN, Kamisah Y and Kamsiah JJVP. (2015). The role of oxidative stress, antioxidants and vascular inflammation in cardiovascular disease(a review). Vascular pharmacology. 71:40-56.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vph.2015.03.005]

-

Sonar SA and Lal G. (2019). The iNOS activity during an immune response controls the CNS pathology in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Frontiers in Immunology. 10:710. https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/immunology/articles/10.3389/fimmu.2019.00710/full, (cited by 2024 June 10).

[https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2019.00710]

-

Stompor-Gorący M. (2021). The health benefits of emodin, a natural anthraquinone derived from rhubarb-A summary update. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 22:9522. https://www.mdpi.com/1422-0067/22/17/95, https://www.mdpi.com/1422-0067/22/17/952222, (cited by 2024 June 10).

[https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms22179522]

-

Sun B, Zheng YL, Yang SK, Zhang JR, Cheng XY, Ghiladi R, Ma Z, Wang J and Deng WW. (2021). One-pot method based on deep eutectic solvent for extraction and conversion of polydatin to resveratrol from Polygonum cuspidatum. Food Chemistry. 343:128498. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0308814620323608, (cited by 2024 June 10).

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2020.128498]

-

Timmen M, Hidding H, Wieskötter B, Baum W, Pap T, Raschke MJ, Schett G, Zwerina J and Stange R. (2014). Influence of antiTNF-alpha antibody treatment on fracture healing under chronic inflammation. BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders. 15:184. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1186/1471-2474-15-184, (cited by 2024 June 10).

[https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2474-15-184]

-

Tramposch KM, Steiner SA, Stanley PL, Nettleton DO, Franson RC, Lewin AH and Carroll FI. (1992). Novel inhibitor of phospholipase A2 with topical anti-inflammatory activity. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 189:272-279.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/0006-291X(92)91554-4]

-

Zhang H, Li C, Kwok ST, Zhang QW and Chan SW. (2013). A review of the pharmacological effects of the dried root of Polygonum cuspidatum(Hu Zhang) and its constituents. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 2013:208349. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1155/2013/208349, (cited by 2024 June 10).

[https://doi.org/10.1155/2013/208349]